ABSTRACT

Diabetic foot disease results in a major global burden for patients and the health care system. The International working Group on the Diabetic Foot (IWGDF) has been producing evidence-based guidelines on the prevention and management of diabetic foot disease since 1999. In 2019, all IWGDF Guidelines have been updated, based on systematic reviews of the literature and formulation of recommendations by multidisciplinary experts from all over the world.

In this document, the IWGDF Practical Guidelines, we describe the basic principles of prevention, classification and treatment of diabetic foot disease, based on the six IWGDF Guideline chapters. We also describe the organizational levels to successfully prevent and treat diabetic foot disease according to these principles and provide addenda to assist with foot screening. The information in these practical guidelines is aimed at the global community of healthcare professionals who are involved in the care of persons with diabetes.

Many studies around the world support our belief that implementing these prevention and management principles is associated with a decrease in the frequency of diabetes-related lower-extremity amputations. We hope that these updated practical guidelines continue to serve as reference document to aid health care providers in reducing the global burden of diabetic foot disease.

INTRODUCTION

In these International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot (IWGDF) Practical Guidelines we describe the basic principles of prevention and management of diabetic foot disease. The Practical Guidelines are based on the IWGDF Guidelines 2019, consisting of evidence-based guideline chapters on:

- Prevention of foot ulcers in persons with diabetes (1)

- Offloading foot ulcers in persons with diabetes (2)

- Diagnosis, prognosis and management of peripheral artery disease in patients with a foot ulcer and diabetes (3)

- Diagnosis and treatment of foot infection in persons with diabetes (4)

- Interventions to enhance healing of foot ulcers in persons with diabetes (5)

- Classification of diabetic foot ulcers (6)

The authors, as members of the Editorial Board of the IWGDF, have summarized the information from these six chapters, and also provide additional advice based on expert opinion in selected areas for which the guideline chapters were not able to provide evidence-based recommendations. We refer the reader for details and background to the six evidence-based guideline chapters (1-6) and our development and methodology document (7); should this summary text appear to differ from information of these chapters we suggest the reader defer to the specific guideline chapters (1-6). Because terminology in this multidisciplinary area can sometimes be unclear we have developed a separate IWGDF Definitions and Criteria document (8).

The information in these practical guidelines is aimed at the global community of healthcare professionals involved in the care of persons with diabetes. The principles outlined may have to be adapted or modified based on local circumstances, taking into account regional differences in the socioeconomic situation, accessibility to and sophistication of healthcare resources, and various cultural factors.

Diabetic foot disease

Diabetic foot disease is among the most serious complications of diabetes mellitus. It is a source of major suffering and financial costs for the patient, and also places a considerable burden on the patient’s family, healthcare professionals and facilities and society in general. Strategies that include elements of prevention, patient and staff education, multi-disciplinary treatment, and close monitoring as described in this document can reduce the burden of diabetic foot disease.

Pathophysiology

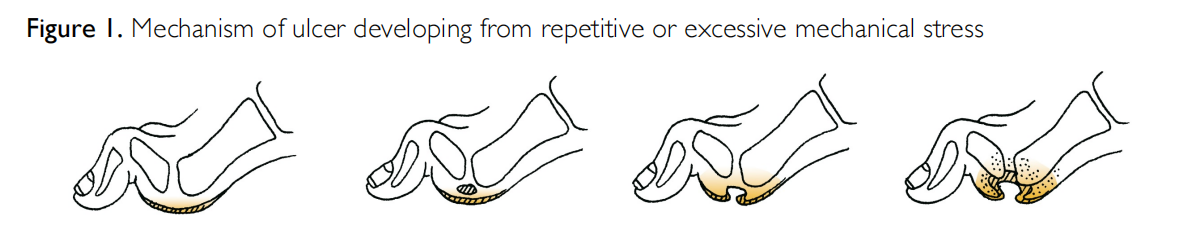

Although both the prevalence and spectrum of diabetic foot disease vary in different regions of the world, the pathways to ulceration are similar in most patients. These ulcers frequently result from a person with diabetes simultaneously having two or more risk factors, with diabetic peripheral neuropathy and peripheral artery disease usually playing a central role. The neuropathy leads to an insensitive and sometimes deformed foot, often causing abnormal loading of the foot. In people with neuropathy, minor trauma (e.g., from ill- fitting shoes, or an acute mechanical or thermal injury) can precipitate ulceration of the foot. Loss of protective sensation, foot deformities, and limited joint mobility can result in abnormal biomechanical loading of the foot. This produces high mechanical stress in some areas, the response to which is usually thickened skin (callus). The callus then leads to a further increase in the loading of the foot, often with subcutaneous haemorrhage and eventually skin ulceration. Whatever the primary cause of ulceration, continued walking on the insensitive foot impairs healing of the ulcer (see Figure 1).

Peripheral artery disease (PAD), generally caused by atherosclerosis, is present in up to 50% of patients with a diabetic foot ulcer. PAD is an important risk factor for impaired wound healing and lower extremity amputation. A small percentage of foot ulcers in patients with severe PAD are purely ischaemic; these are usually painful and may follow minor trauma. The majority of foot ulcers, however, are either purely neuropathic or neuro-ischaemic, i.e., caused by combined neuropathy and ischaemia. In patients with neuro-ischaemic ulcers, symptoms may be absent because of the neuropathy, despite severe pedal ischaemia. Recent studies suggest that diabetic microangiopathy (so-called “small vessel disease”) does not appear to be the primary cause of either ulcers or of poor wound healing.

CORNERSTONES OF FOOT ULCER PREVENTION

There are five key elements that underpin efforts to prevent foot ulcers:

1. Identifying the at-risk foot

2. Regularly inspecting and examining the at-risk foot

3. Educating the patient, family and healthcare professionals

4. Ensuring routine wearing of appropriate footwear

5. Treating risk factors for ulceration

An appropriately trained team of healthcare professionals should address these five elements as part of integrated care for people at high risk of ulceration (IWGDF risk stratification 3).

1. Identifying the at-risk foot

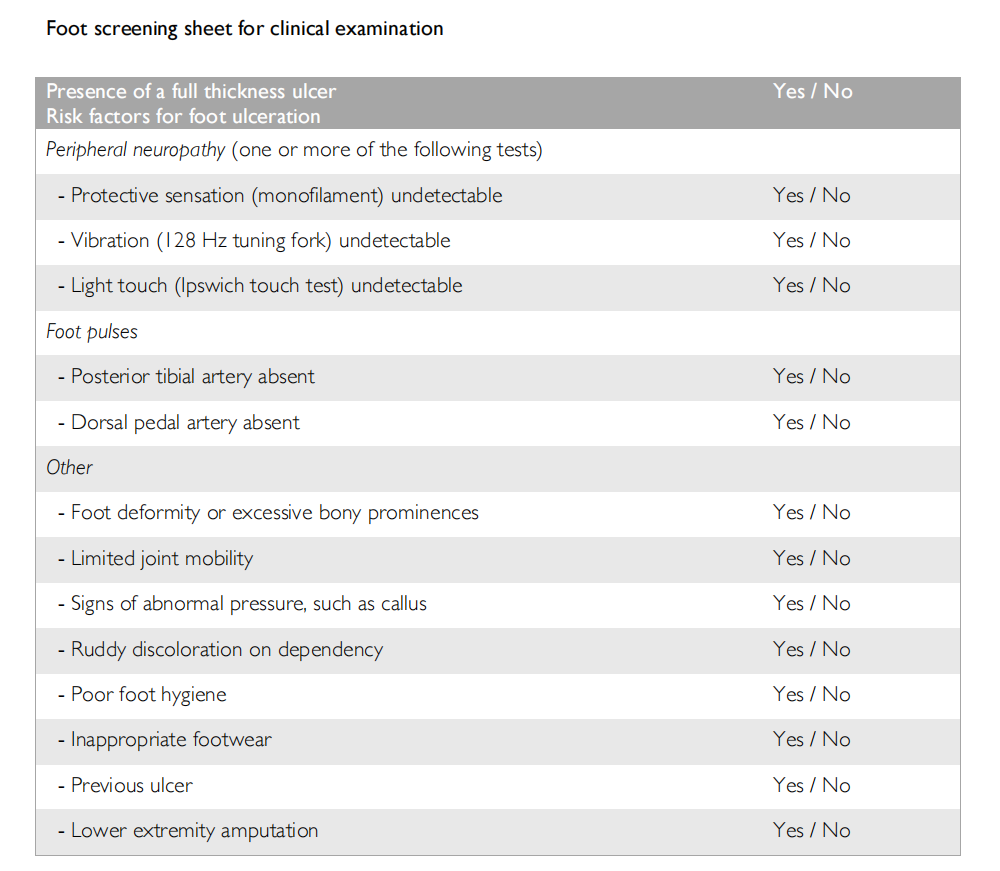

The absence of symptoms in a person with diabetes does not exclude foot disease; they may have asymptomatic neuropathy, peripheral artery disease, pre-ulcerative signs, or even an ulcer. Examine a person with diabetes at very low risk of foot ulceration (IWGDF risk 0) annually for signs or symptoms of loss of protective sensation and peripheral artery disease, to identify if they are at-risk for foot ulceration, including doing the following:

- History: Previous ulcer/lower extremity amputation, claudication

- Vascular status: palpation of pedal pulses

- Loss of protective sensation (LOPS): assess with one of the following techniques

(see addendum for details):

- Pressure perception: Semmes-Weinstein 10 gram monofilament

- Vibration perception: 128 Hz tuning fork

- When monofilament or tuning fork are not available test tactile sensation: lightly touch the tips of the toes of the patient with the tip of your index finger for 1–2 seconds

LOPS is usually caused by diabetic polyneuropathy. If present, it is usually necessary to elicit further history and conduct further examinations into its causes and consequences; these are outside the scope of this guideline.

2. Regularly inspecting and examining the at-risk foot (IWGDF risk 1 or higher) In a person with diabetes with loss of protective sensation or peripheral artery disease (IWGDF risk 1-3) perform a more comprehensive examination, including the following:

- History: inquiring about previous ulcer/lower extremity amputation, end stage renal disease,previous foot education, social isolation, poor access to healthcare and financial constraints, foot pain (with walking or at rest) or numbness, claudication

- Vascular status: palpation of pedal pulses

- Skin: assessing for skin colour, temperature, presence of callus or oedema, pre-ulcerative signs

- Bone/joint: check for deformities (e.g., claw or hammer toes), abnormally large bony prominences, or limited joint mobility. Examine the feet with the patient both lying down and standing up

- Assessment for loss of protective sensation (LOPS), if on a previous examination protective sensation was intact

- Footwear: ill-fitting, inadequate, or lack of footwear.

- Poor foot hygiene, e.g. improperly cut toenails, unwashed feet, superficial fungal infection, or unclean socks

- Physical limitations that may hinder foot self-care (e.g. visual acuity, obesity)

- Foot care knowledge

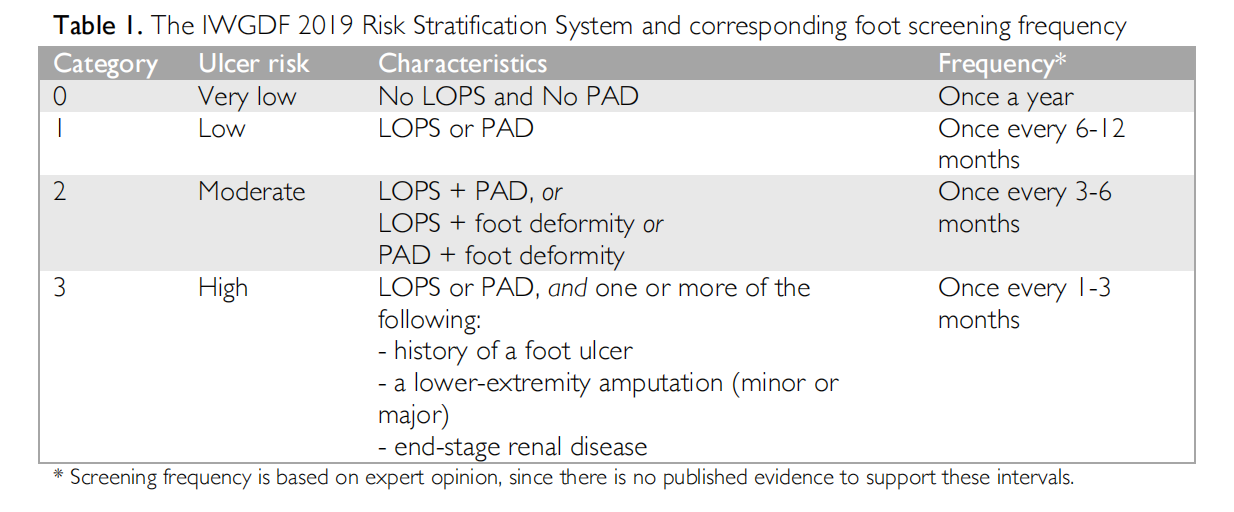

Following examination of the foot, stratify each patient using the IWGDF risk stratification category system shown in Table 1 to guide subsequent preventative screening frequencies and management. Areas of the foot most at-risk are shown in Figure 2. Any foot ulcer identified during screening should be treated according to the principles outlined below.

3. Educating patients, family and healthcare professionals about foot care

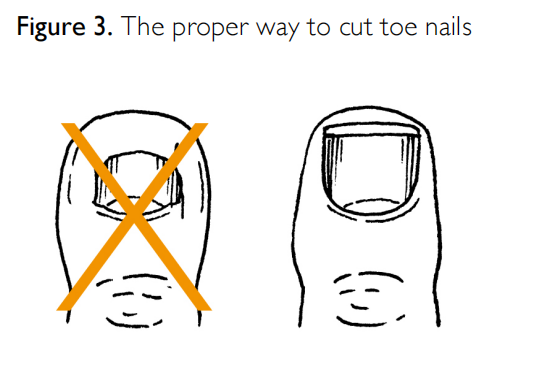

Education, presented in a structured, organized and repeated manner, is widely considered to play an important role in the prevention of diabetic foot ulcers. The aim is to improve a patient’s foot self-care knowledge and self-protective behaviour, and to enhance their motivation and skills to facilitate adherence to this behaviour. People with diabetes, in particular those with IWGDF risk 1 or higher, should learn how to recognize foot ulcers and pre-ulcerative signs and be aware of the steps they need to take when problems arise. The educator should demonstrate specific skills to the patient, such as how to cut toe nails appropriately (Figure 3). A member of the healthcare team should provide structured education (see examples of instructions below) individually or in small groups of people, in multiple sessions, with periodical reinforcement, and preferably using a mixture of methods. The structured education should be culturally appropriate, account for gender differences, and align with a patient’s health literacy and personal circumstances. It is essential to assess whether the person with diabetes (and, optimally, any close family member or carer) has understood the messages, is motivated to act and adhere to the advice, to ensure sufficient self-care skills. Furthermore, healthcare professionals providing these instructions should receive periodic education to improve their own skills in the care for people at high-risk for foot ulceration.

Items to cover when educating the person at-risk for foot ulceration (IWGDF risk 1 or higher):

- Determine if the person is able to perform a foot inspection. If not, discuss who can assist the person in this task. Persons who have substantial visual impairment or physical inability to visualise their feet cannot adequately do the inspection

- Explain the need to perform daily foot inspection of the entire surface of both feet, including areas between the toes

- Ensure the patient knows how to notify the appropriate healthcare professional if measured foot temperature is perceptibly increased, or if a blister, cut, scratch or ulcer has developed

- Review the following practices with the patient:

- Avoid walking barefoot, in socks without footwear, or in thin-soled slippers, whether at home or outside

- Do not wear shoes that are too tight, have rough edges or uneven seams

- Visually inspect and manually feel inside all shoes before you put them on

- Wear socks/stocking without seams (or with the seams inside out); do not wear tight or kneehigh socks (compressive stocking should only be prescribed in collaboration with the foot care team), and change socks daily

- Wash feet daily (with water temperature always below 37°C), and dry them carefully, especially between the toes

- Do not use any kind of heater or a hot-water bottle to warm feet

- Do not use chemical agents or plasters to remove corns and calluses; see the appropriate healthcare professional for these problems

- Use emollients to lubricate dry skin, but not between the toes

- Cut toenails straight across (see Figure 3)

- Have your feet examined regularly by a healthcare professional

4. Ensuring routine wearing of appropriate footwear

In persons with diabetes and insensate feet, wearing inappropriate footwear or walking barefoot are major causes of foot trauma leading to foot ulceration. Persons with loss of protective sensation (LOPS) must have (and may need financial assistance to acquire) and should be encouraged to wear, appropriate footwear at all times, both indoors and outdoors. All footwear should be adapted to conform to any alteration in foot structure or foot biomechanics affecting the person’s foot. People without LOPS or PAD (IWGDF 0) can select properly fitting off-the-shelf footwear. People with LOPS or PAD (IWGDF 1-3) must take extra care when selecting, or being fitted with, footwear; this is most important when they also have foot deformities (IWGDF 2) or have a history of a previous ulcer/amputation (IWGDF 3).

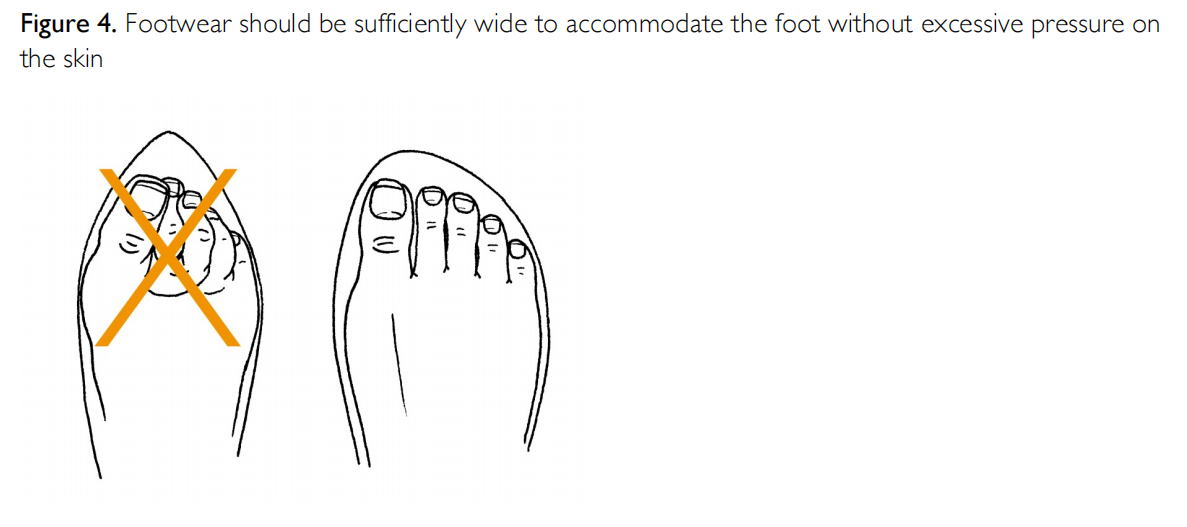

The inside length of the shoe should be 1-2 cm longer than their foot and should not be either too tight or too loose (see Figure 4). The internal width should equal the width of the foot at the metatarsal phalangeal joints (or the widest part of the foot), and the height should allow enough room for all the toes. Evaluate the fit with the patient in the standing position, preferably later in the day (when they may have foot swelling). If there is no off-the-shelf footwear that can accommodate the foot (e.g., if the fit is poor due to foot deformity) or if there are signs of abnormal loading of the foot (e.g., hyperaemia, callus, ulceration), refer the patient for special footwear (advice and/or construction), possibly including extra-depth shoes, custom-made shoes, insoles, or orthoses.

To prevent a recurrent plantar foot ulcer, ensure that a patient’s therapeutic footwear has a demonstrated plantar pressure relieving effect during walking. When possible, demonstrate this plantar pressure relieving effect with appropriate equipment, as described elsewhere (1). Instruct the patient to never again wear the same shoe that has caused an ulcer.

5. Treating risk factors for ulceration

In a patient with diabetes treat any modifiable risk factor or pre-ulcerative sign on the foot. This includes: removing abundant callus; protecting blisters, or draining them if necessary; appropriately treating ingrown or thickened nails; and, prescribing antifungal treatment for fungal infections. This treatment should be repeated until these abnormalities resolve and do not recur over time, and should be performed by an appropriately trained healthcare professional. In patients with recurrent ulcers due to foot deformities that develop despite optimal preventive measures as described above, consider surgical intervention.

ASSESSMENT AND CLASSIFICATION OF FOOT ULCERS

Health care professionals should follow a standardized and consistent strategy for evaluating a foot ulcer, as this will guide further evaluation and therapy. The following items should be addressed:

Type

By history and clinical examination, classify the ulcer as neuropathic, neuro-ischaemic or ischaemic. LOPS is characteristic for a neuropathic ulcer. As a first step in seeking the presence of PAD, take a symptomdirected history and palpate the foot for pedal pulses. That said, there are no specific symptoms or signs of PAD that reliably predict healing of the ulcer. Therefore, examine the arterial pedal wave forms and measure the ankle pressure and ankle brachial index (ABI), using a Doppler instrument. The presence of an ABI 0.9-1.3 or a triphasic pedal pulse waveform largely excludes PAD, as does a toe brachial index (TBI) ≥0.75. However, ankle pressure and ABI can be falsely elevated due to calcification of the pedal arteries. In selected cases, other tests, such as measurements of toe pressure or transcutaneous pressure of oxygen (TcpO2), are useful to assess the vascular status of the foot.

Cause

Wearing ill-fitting shoes and walking barefoot are practices that frequently lead to foot ulceration, even in patients with exclusively ischaemic ulcers. Therefore, meticulously examine shoes and footwear behaviour in every patient with a foot ulcer.

Site and depth

Neuropathic ulcers most frequently develop on the plantar surface of the foot, or in areas overlying a bony deformity. Ischemic and neuro-ischemic ulcers more commonly develop on the tips of the toes or

the lateral borders of the foot.

Determining the depth of a foot ulcer can be difficult, especially in the presence of overlying callus or necrotic tissue. To aid assessment of the ulcer, debride any neuropathic or neuro-ischemic ulcers that is surrounded by callus or contains necrotic soft tissue at initial presentation, or as soon as possible. Do not, however, debride a non-infected ulcer that has signs of severe ischemia. Neuropathic ulcers can usually be debrided without the need for local anaesthesia.

Signs of infection

Infection of the foot in a person with diabetes presents a serious threat to the affected foot and limb and must be evaluated and treated promptly. Because all ulcers are colonised with potential pathogens, diagnose infection by the presence of at least two signs or symptoms of inflammation (redness, warmth, induration, pain/tenderness) or purulent secretions. Unfortunately, these signs may be blunted by neuropathy or ischaemia, and systemic findings (e.g., pain, fever, leucocytosis) are often absent in mild and moderate infections. Infections should be classified using the IDSA/IWGDF scheme as mild (superficial with minimal cellulitis), moderate (deeper or more extensive) or severe (accompanied by systemic signs of sepsis), as well as whether or not they are accompanied by osteomyelitis (4).

If not properly treated, infection can spread contiguously to underlying tissues, including bone (osteomyelitis). Assess patients with a diabetic foot infection for the presence of osteomyelitis, especially if the ulcer is longstanding, deep, or located directly over a prominent bone. Examine the ulcer to determine if it is possible to visualise or touch bone with a sterile metal probe. In addition to the clinical evaluation, consider obtaining plain radiographs in most patients seeking evidence for osteomyelitis, tissue gas or foreign body. When more advanced imaging is needed consider magnetic resonance imaging, or for those in whom this is not possible, other techniques (e.g., radionuclide or PET scans).

For clinically infected wounds obtain a tissue specimen for culture (and Gram-stained smear, if available); avoid obtaining specimens for wound cultures with a swab. The causative pathogens of foot infection (and their antibiotic susceptibilities) vary by geographic, demographic and clinical situations, but Staphylococcus aureus (alone, or with other organisms) is the predominant pathogen in most cases. Chronic and more severe infections are often polymicrobial, with aerobic gram-negative rods and anaerobes accompanying the gram-positive cocci, especially in warmer climates.

Patient related factors

Apart from a systematic evaluation of the ulcer, the foot and the leg, also consider patient related factors that can affect wound healing, such as end-stage renal disease, oedema, malnutrition, poor metabolic control or psycho-social problems.

Ulcer classification

Assess the severity of infection using the IWGDF/ISDA classification criteria (4,6) and in patients with PAD we recommend using the WIfI (wound/ischaemia/infection) system to stratify amputation risk and revascularisation benefit (3,6). For communication among healthcare professionals we recommend the SINBAD system, which can also be used for audit of outcome of populations (6).

PRINCIPLES OF ULCER TREATMENT

Foot ulcers will heal in the majority of patients if the clinician bases treatment on the principles outlined below. However, even optimum wound care cannot compensate for continuing trauma to the wound bed, or for inadequately treated ischemia or infection. Patients with an ulcer deeper than the subcutaneous tissues often require intensive treatment, and, depending on their social situation, local resources and infrastructure, they may need to be hospitalised.

1. Pressure offloading and ulcer protection

Offloading is a cornerstone in treatment of ulcers that are caused by increased biomechanical stress:

- The preferred offloading treatment for a neuropathic plantar ulcer is a non-removable knee-high offloading device, i.e, either a total contact cast (TCC) or removable walker rendered (by the provider fitting it) irremovable

- When a non-removable knee-high offloading device is contraindicated or not tolerated by the patient, consider using a removable knee-high offloading device. If such a device is contraindicated or not tolerated, consider using an ankle-high offloading device. Always educate the patient on the benefits of adherence to wearing the removable device.

- If other forms of biomechanical relief are not available, consider using felted foam, but only in combination with appropriate footwear

- When infection or ischemia are present, offloading is still important, but be more cautious, as discussed in the IWGDF offloading guideline (2).

- For non-plantar ulcers, use a removable ankle-high offloading device, footwear modifications, toe spacers, or orthoses depending on the type and location of the foot ulcer.

2. Restoration of tissue perfusion

- In patients with either an ankle pressure <50mm Hg or an ABI <0.5 consider urgent vascular imaging and, when findings suggest it is appropriate, revascularisation. Also consider revascularisation if the toe pressure is <30mmHg or TcpO2 is <25 mmHg. However, clinicians might consider revascularisation at higher pressure levels in patients with extensive tissue loss or infection, as discussed in more detail in the IWGDF PAD Guideline (3)

- When an ulcer fails to show signs of healing within 6 weeks, despite optimal management, consider revascularisation, irrespective of the results of the vascular diagnostic tests described above

- If contemplating a major (i.e., above the ankle) amputation, first consider the option of revascularization

- The aim of revascularisation is to restore direct flflow to at least one of the foot arteries, preferably the artery that supplies the anatomical region of the wound. But, avoid revascularisation in patients in whom, from the patient perspective, the risk–benefit ratio for the probability of success is unfavourable

- Select a revascularisation technique based on both individual factors (such as morphological distribution of PAD, availability of autogenous vein, patient co-morbidities) and local operator expertise.

-

After a revascularisation procedure, its effectiveness should be evaluated with an objective measurement of perfusion.

-

Pharmacological treatments to improve perfusion have not been proven to be beneficial.

-

Emphasise efforts to reduce cardiovascular risk (cessation of smoking, control of hypertension and dyslipidaemia, use of anti-platelet drugs)

3. Treatment of infection

Superficial ulcer with limited soft tissue (mild) infection:

- Cleanse, debride all necrotic tissue and surrounding callus

- Start empiric oral antibiotic therapy targeted at Staphylococcus aureus and streptococci (unless there are reasons to consider other, or additional, likely pathogens)

Deep or extensive (potentially limb-threatening) infection (moderate or severe infection):

- Urgently evaluate for need for surgical intervention to remove necrotic tissue, including infected bone, release compartment pressure or drain abscesses

- Assess for PAD; if present consider urgent treatment, including revascularisation

- Initiate empiric, parenteral, broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy, aimed at common gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, including obligate anaerobes

- Adjust (constrain and target, if possible) the antibiotic regimen based on both the clinical response to empirical therapy and culture and sensitivity results

4. Metabolic control and treatment of co-morbidities

- Optimise glycaemic control, if necessary with insulin

- Treat oedema or malnutrition, if present

5. Local ulcer care

- Regular inspection of the ulcer by a trained health care provider is essential, its frequency depends on the severity of the ulcer and underlying pathology, the presence of infection, the amount of exsudation and wound treatment provided

- Debride the ulcer and remove surrounding callus (preferably with sharp surgical instruments), and repeat as needed

- Select dressings to control excess exudation and maintain moist environment

- Do not soak the feet, as this may induce skin maceration.

- Consider negative pressure to help heal post-operative wounds Consider one of the following adjunctive treatments in non-infected ulcers that fail to heal after 4-6 weeks despite optimal clinical care:

- A sucrose octasulfate impregnated dressing in neuro-ischemic ulcers (without severe ischemia)

-

A multi-layered patch of autologous leucocytes, platelets and fibrin in ulcers with or without moderate ischemia

-

Placental membrane allografts in ulcers with or without moderate ischemia

-

Systemic oxygen therapy as an adjunctive treatment in ischaemic ulcers that do not heal despite revascularisation

The following treatments are not well-supported for routine ulcer management:

- Biologically active products (collagen, growth factors, bio- engineered tissue) in neuropathic ulcers

- Silver, or other antimicrobial agent, containing dressings or topical applications

6. Education for patient and relatives

- Instruct patients (and relatives or carers) on appropriate foot ulcer self-care and how to recognize and report signs and symptoms of new or worsening infection (e.g., onset of fever, changes in local wound conditions, worsening hyperglycaemia)

- During a period of enforced bed rest, instruct on how to prevent an ulcer on the contra- lateral foot

ORGANIZATION OF CARE FOR DIABETIC FOOT DISEASE

Successful efforts to prevent and treat diabetic foot disease depend upon a well-organised team, that uses a holistic approach in which the ulcer is seen as a sign of multi-organ disease, and that integrates the various disciplines involved. Effective organisation requires systems and guidelines for education, screening, risk reduction, treatment, and auditing. Local variations in resources and staffing often dictate how to provide care, but ideally a diabetic foot disease programme should provide the following:

- Education for people with diabetes and their carers, for healthcare staff in hospitals and for primary healthcare professionals

- Systems to detect all people who are at risk, including annual foot examination of all persons with diabetes

- Access to measures for reducing risk of foot ulceration, such as podiatric care and provision of appropriate footwear

- Ready access to prompt and effective treatment of any foot ulcer or infection

- Auditing of all aspects of the service to identify and address problems and ensure that local practice meets accepted standards of care

- An overall structure designed to meet the needs of patients requiring chronic care, rather than simply responding to acute problems when they occur.

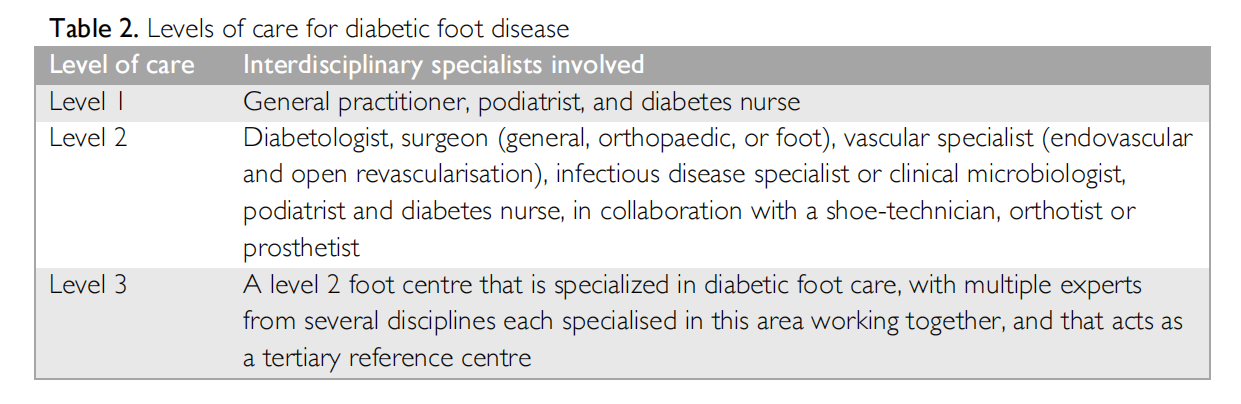

In all countries, there should optimally be at least three levels of foot-care management with interdisciplinary specialists like those listed in Table 2.

Studies around the world have shown that setting up an interdisciplinary foot care team and implementing prevention and management of diabetic foot disease according to the principles outlined in this guideline, is associated with a decrease in the frequency of diabetes related lower-extremity amputations. If it is not possible to create a full team from the outset, aim to build one step-by-step, introducing the various disciplines as possible. This team must first and foremost act with mutual respect and understanding, work in both primary and secondary care settings, and have at least one member available for consultation or patient assessment at all times. We hope that these updated practical guidelines and the underlying six evidence-based guideline chapters continue to serve as reference document to reduce the burden of diabetic foot disease.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to the 49 working group members who have collaborated tirelessly, lending their time, expertise and passion to the realization of the IWGDF guideline project. We would also like to thank the 50 independent external experts for their time to review our clinical questions and guidelines. In addition, we sincerely thank the sponsors who, by providing generous and unrestricted educational grants, made development of these guidelines possible.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENTS

Production of the 2019 IWGDF Guidelines was supported by unrestricted grants from: Molnlycke Healthcare, Acelity, ConvaTec, Urgo Medical, Edixomed, Klaveness, Reapplix, Podartis, Aurealis, SoftOx, Woundcare Circle, and Essity. These sponsors did not have any communication related to the systematic reviews of the literature or related to the guidelines with working group members during the writing of the guidelines, and have not seen any guideline or guideline-related document before

All individual conflict of interest statement of authors of this guideline can be found at: www. iwgdfguidelines.org/about-iwgdf-guidelines/biographies

VERSION

Please note that this guideline has been fully refereed and reviewed, but has not yet been through the copyediting, typesetting, pagination and proofreading process. Thus, it should not be considered the Version of Record. This guideline might still contain errors or otherwise deviate from the later published final version. Once the final version of the manuscript is published online, this current version will be replaecd.

REFERENCES

(1) Bus SA; Lavery LA; Monteiro-Soares M; Rasmussen A; Raspovic A; Sacco ICN; Van Netten JJ; on behalf of the International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot (IWGDF). IWGDF guideline on the prevention of foot ulcers in persons with diabetes. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2019; in press.

(2) Bus SA, Armstrong DG, Gooday C; Jarl G; Caravaggi CF, Viswanathan V; Lazzarini PA; on behalf of the the International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot (IWGDF). IWGDF Guideline on offloading foot ulcers in persons with diabetes. Diabetes Metab.Res.Rev. 2019; in press.

(3) Hinchliffe RJ, Forsythe R, Apelqvist J, Boyko EJ, Fitridge R, Hong JP, et al. IWGDF Guideline on diagnosis, prognosis and management of peripheral artery disease in patients with a foot ulcer and diabetes. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2019; in press.

(4) Lipsky BA, Senneville , Abbas Z, Aragón-Sánchez J, Diggle M, Embil J, et al. IWGDF Guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of foot infection in persons with diabetes. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2019; in press.

(5) Rayman G, Vas P, Dhatariya K, Driver V, Hartemann A, Londahl M, et al. IWGDF Guideline on interventions to enhance healing of foot ulcers in persons with diabetes. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2019; in press.

(6) Monteiro-Soares M, Russell D, Boyko EJ, Jeffcoate W, Mills JL, Morbach S, Game F. IWGDF Guidelines on the classification of diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2019; in press.

(7) Bus SA, Van Netten JJ, Apelqvist J, Hinchliffe RJ, Lipsky BA, Schaper NC. Development and methodology of the 2019 IWGDF Guidelines. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2019; in press.

(8) IWGDF Editorial Board. IWGDF Definitions and Criteria. 2019; Available at: https://iwgdfguidelines.org/definitions criteria/. Accessed 04/23, 2019.

ADDENDUM

Doing a sensory foot examination

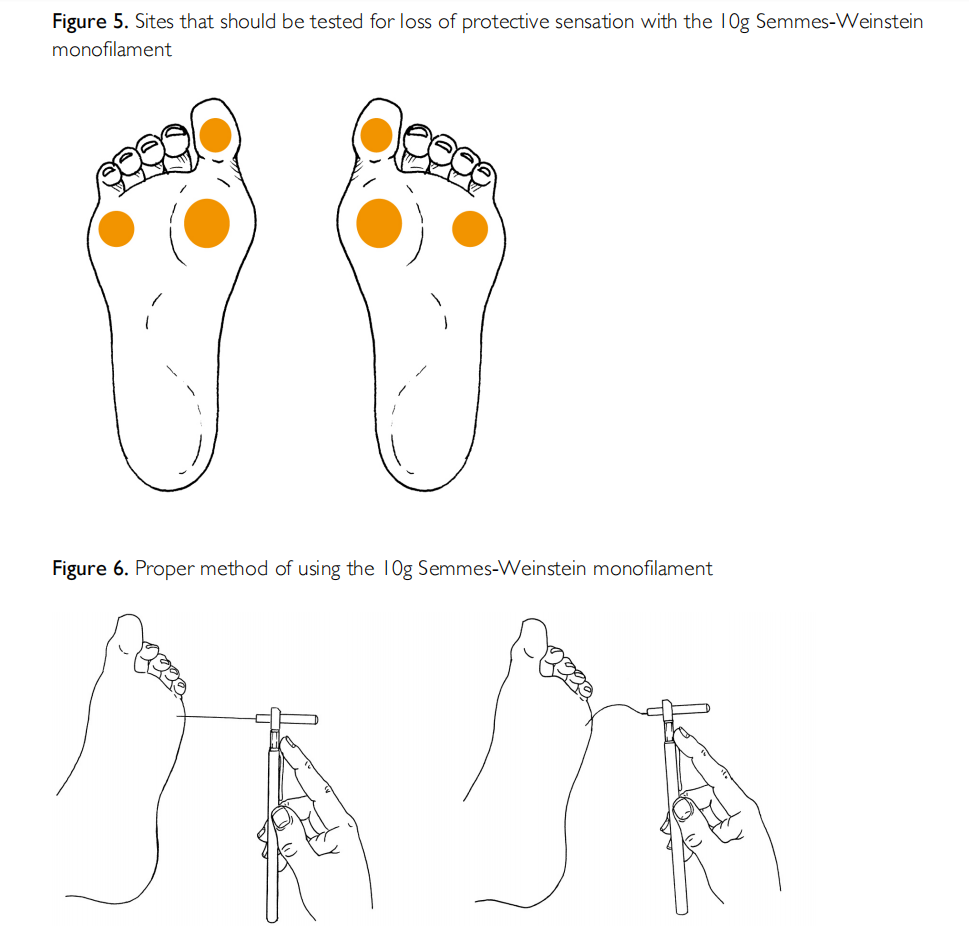

Peripheral neuropathy can be detected using the 10g (5.07 Semmes-Weinstein) monofilament (detects loss of protective sensation) and a tuning fork (128 Hz, detects loss of vibratory sensation). 10g (5.07) Semmes-Weinstein monofilament (Figures 5 and 6)

- First apply the monofilament on the patient's hands (or elbow or forehead) to demonstrate what the sensation feels like.

- Test three different sites on both feet, selecting from those shown in Figure 5.

- Ensure the patient cannot see whether or where the examiner applies the filament.

- Apply the monofilament perpendicular to the skin surface (Figure 6a) with sufficient force to cause the filament to bend or buckle (Figure 6b).

- The total duration of the approach -> skin contact -> and removal of the filament should be approximately 2 seconds.

- Do not apply the filament directly on an ulcer, callus, scar or necrotic tissue.

- Do not allow the filament to slide across the skin or make repetitive contact at the test site.

- Press the filament to the skin and ask the patient whether they feel the pressure applied ('yes'/'no') and next where they feel the pressure (e.g., 'ball of left foot'/'right heel).

- Repeat this application twice at the same site, but alternate this with at least one 'mock' application in which no filament is applied (a total of three questions per site).

- Protective sensation is: present at each site if the patient correctly answers on two out of three applications; absent with two out of three incorrect answers.

- Encourage the patients during testing by giving positive feedback. Monofilaments tend to lose buckling force temporarily after being used several times on the same day, or permanently after long duration use. Depending on the type of monofilament, we suggest not using the monofilament for the next 24 hours after assessing 10-15 patients and replacing it after using it on 70-90 patients.

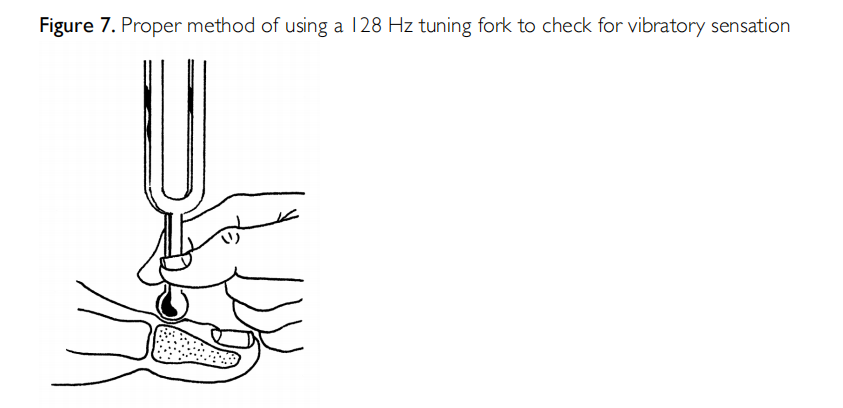

128 Hz Tuning fork (Figure 7)

- First, apply the tuning fork on the patient's wrist (or elbow or clavicle) to demonstrate what the sensation feels like.

- Ensure the patient cannot see whether or where the examiner applies the tuning fork.

- Apply the tuning fork to a bony part on the dorsal side of the distal phalanx of the first toe (or another toe if the hallux is absent).

- Apply the tuning fork perpendicularly, with constant pressure (Figure 7).

- Repeat this application twice, but alternate this with at least one 'mock' application in which the tuning fork is not vibrating.

- The test is positive if the patient correctly answers at least two out of three applications, and negative if two out of three answers are incorrect.

- If the patient is unable to sense the vibrations on the toe, repeat the test more proximally (e.g., malleolus, tibial tuberosity).

- Encourage the patient during testing by giving positive feedback.

Light touch test

This simple test (also called the Ipswich Touch test) can be used to screen for loss of protective sensation (LOPS), when the 10 gram monofilament or 128 HZ tuning fork is not available. The test has reasonable agreement with these tests to determine LOPS, but its accuracy in predicting foot ulcers has not been established.

- Explain the procedure and ensure that everything is understood

- Instruct the subject to close the eyes and to say yes when they feel the touch

- The examiner lightly sequentially touches with the tip of hers/his index finger the tips of the first, third, and fifth toes of both feet for 1–2 s

- When touching, do not push, tap, or poke

- LOPS is likely when light touch is not sensed in ≥ 2 sites

This article is excerpted from the © 2019 The International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot by Wound World.