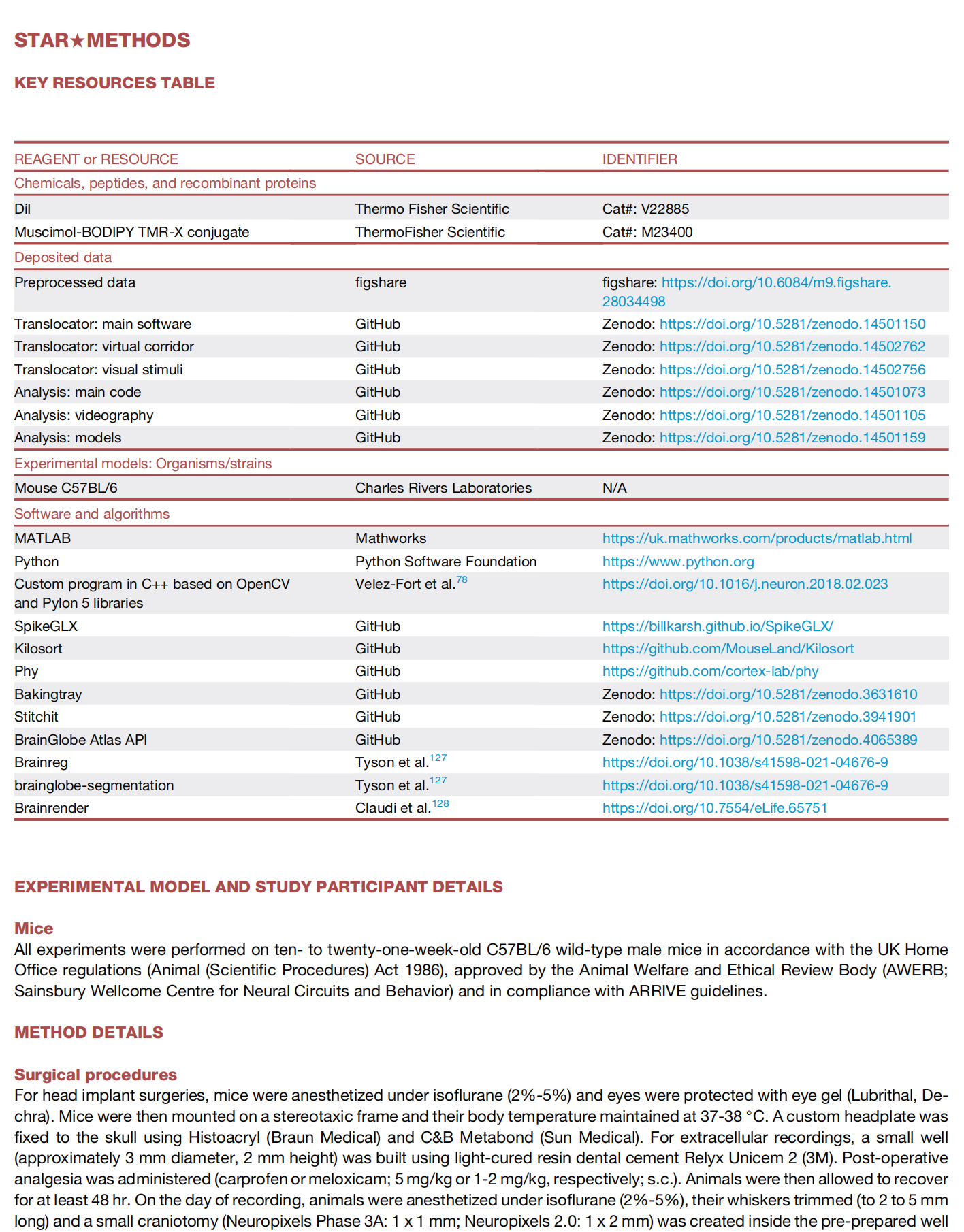

This article is excerpted from the Cell 188, 2175–2189, April 17, 2025 by Wound World.

Mateo Ve´ lez-Fort,1,3 Lee Cossell,1,3 Laura Porta,1 Claudia Clopath,1,2 and Troy W. Margrie1,4,*

1 Sainsbury Wellcome Centre, University College London, London, UK

2 Bioengineering Department, Imperial College London, London, UK

3 These authors contributed equally

4 Lead contact

*Correspondence: 该Email地址已收到反垃圾邮件插件保护。要显示它您需要在浏览器中启用JavaScript。

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2025.01.032

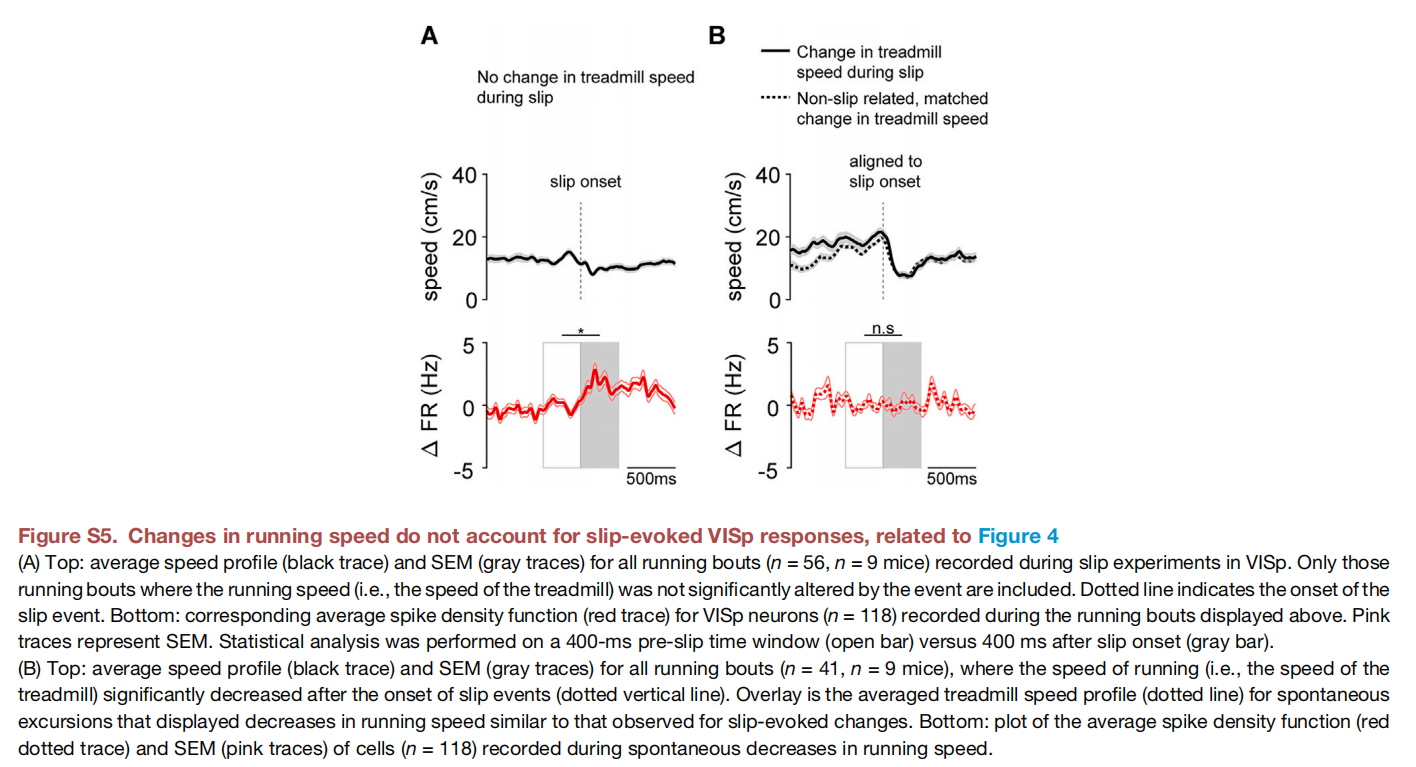

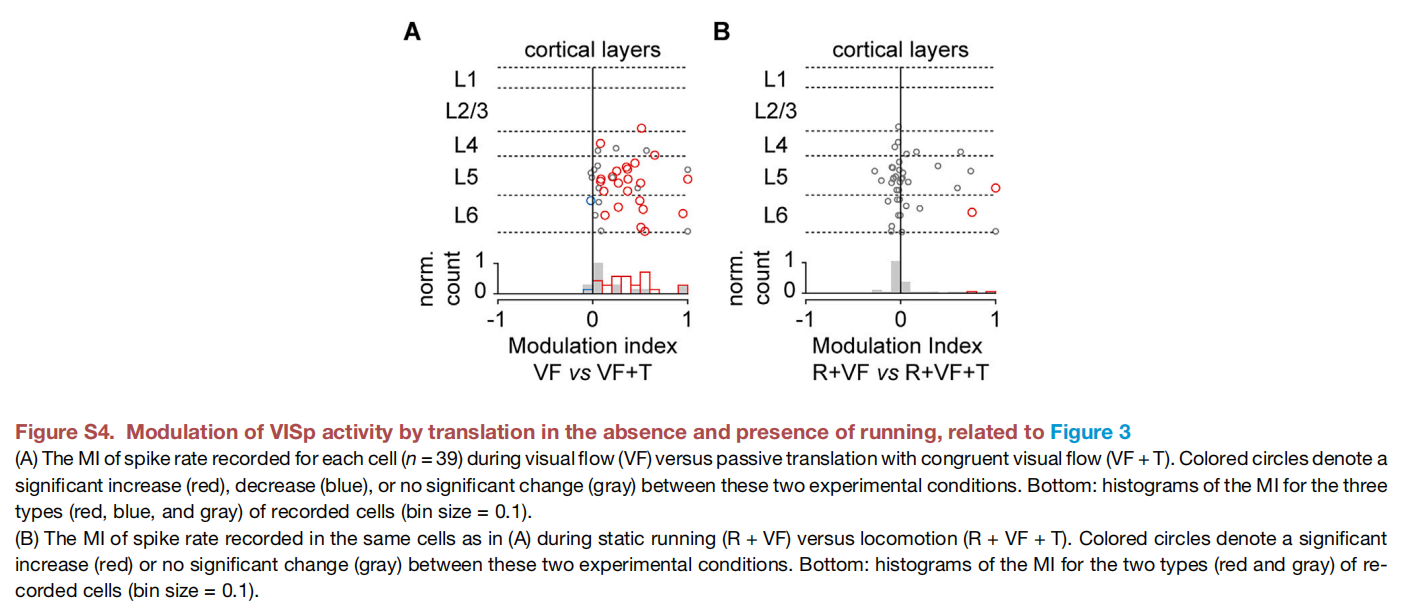

SUMMARY

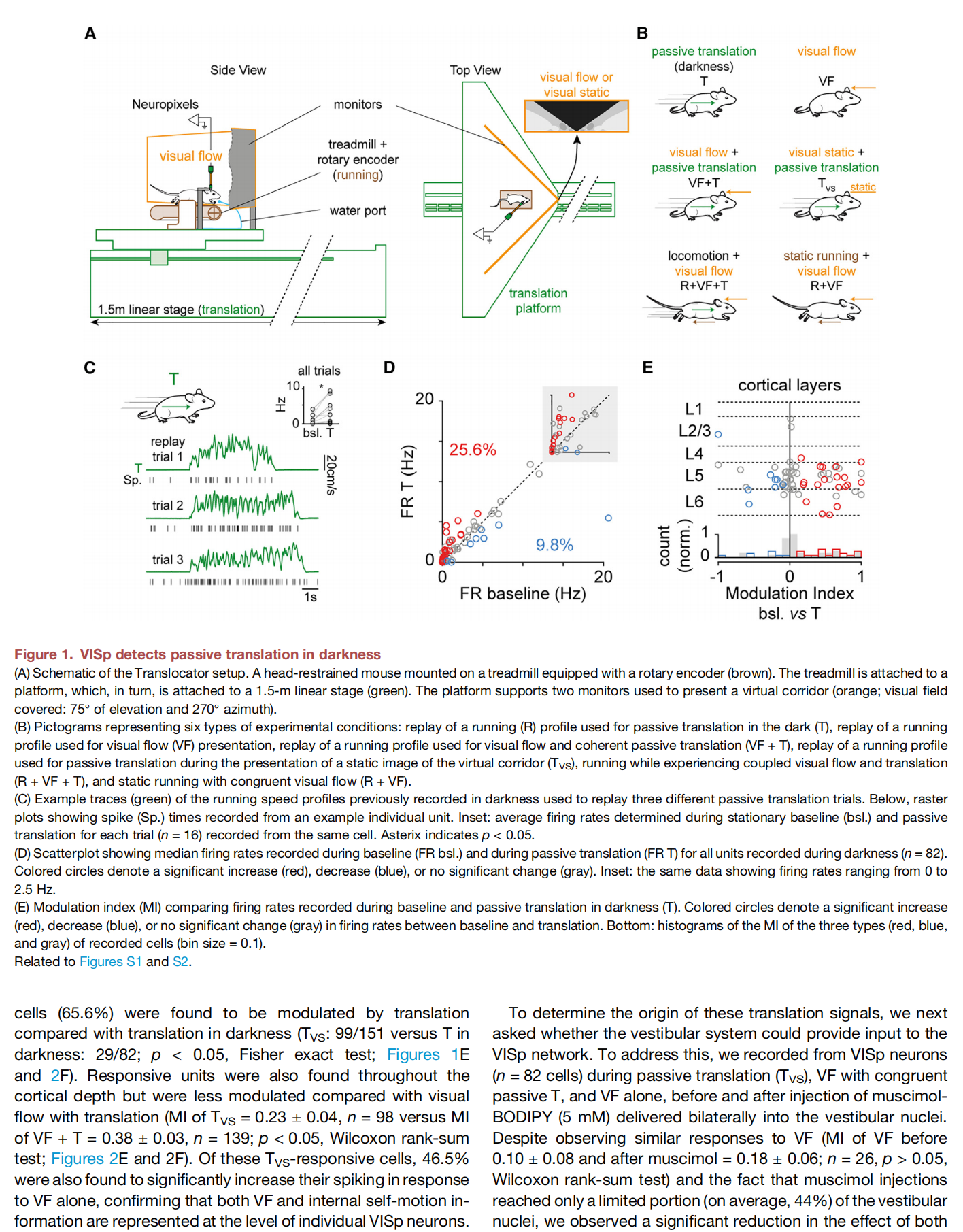

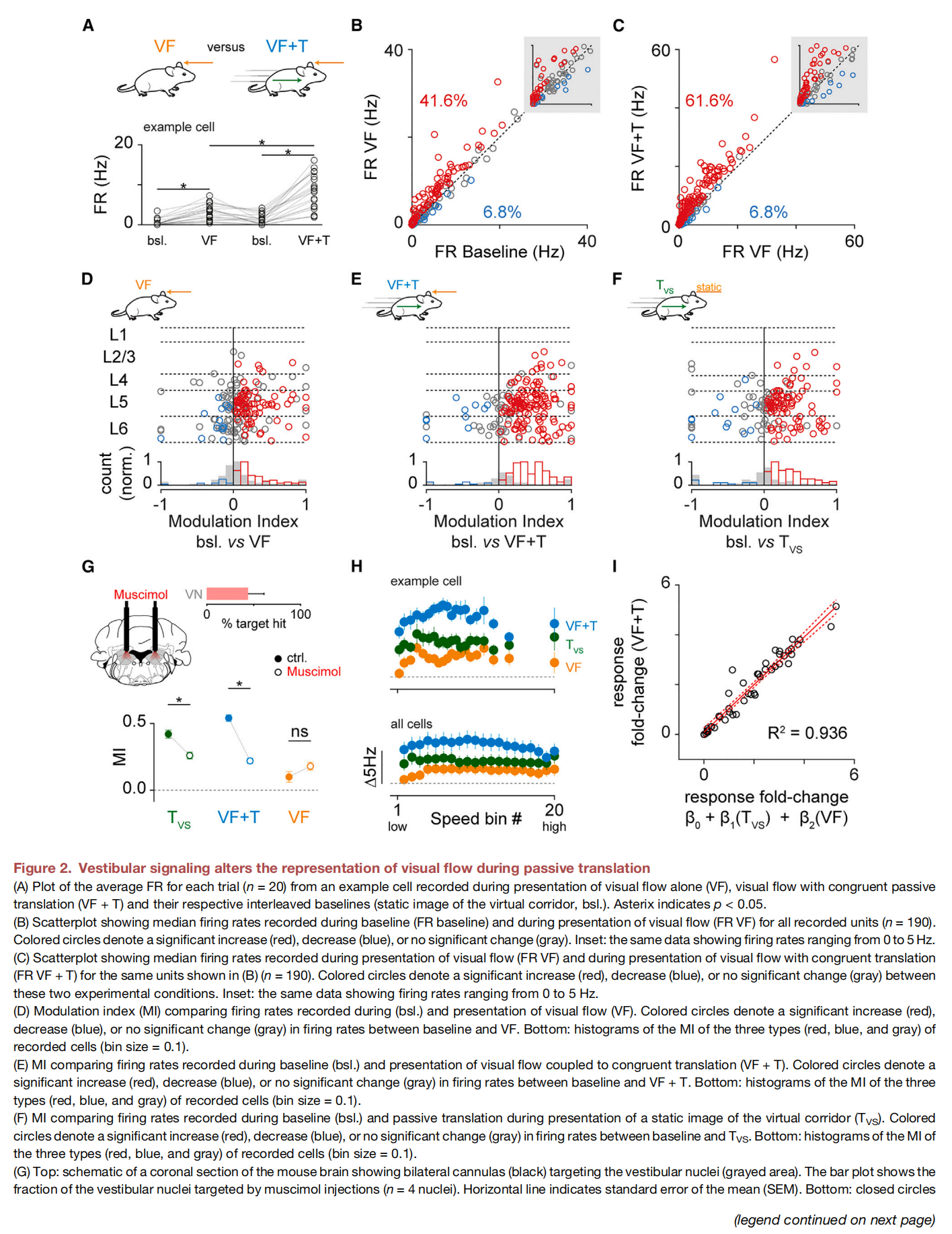

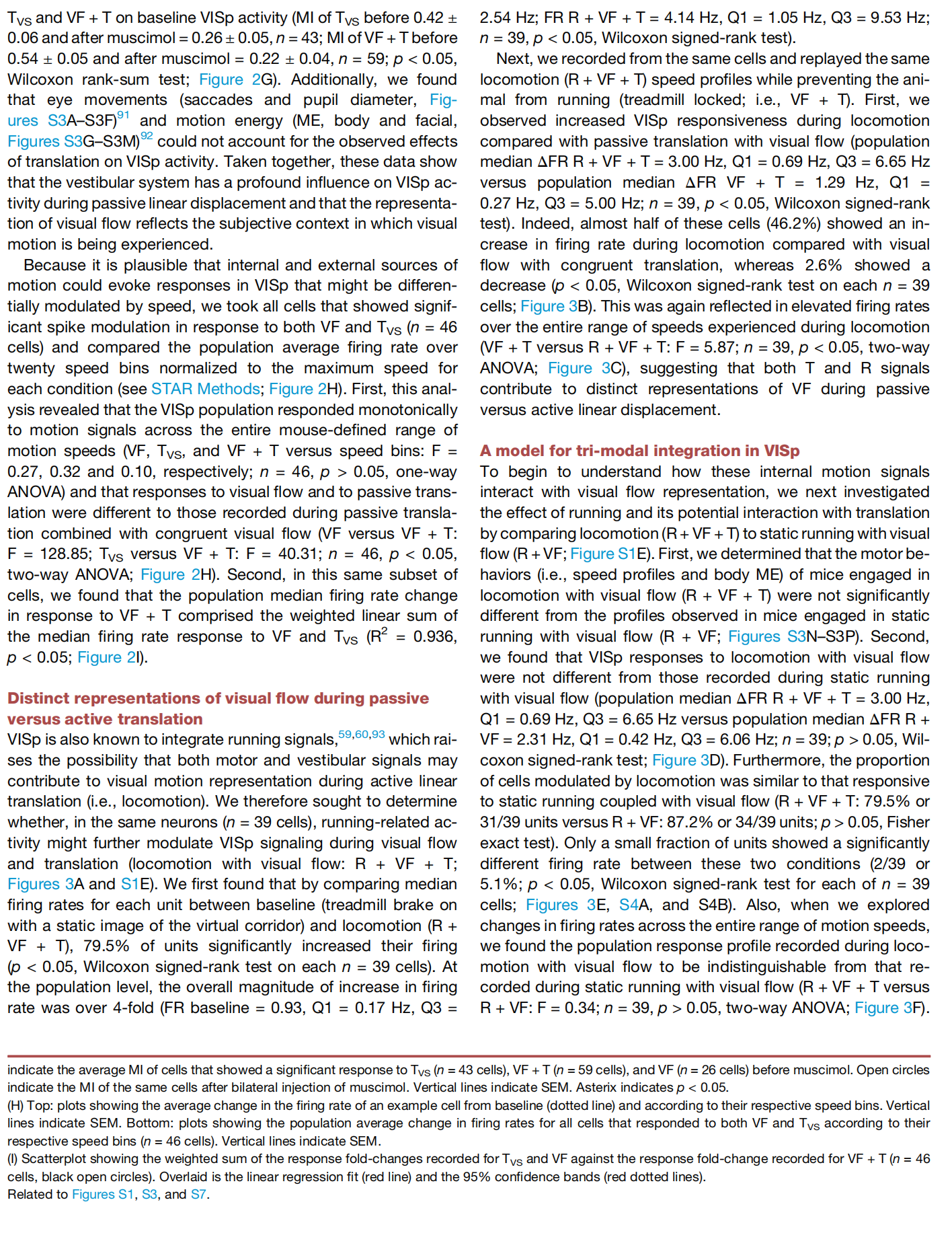

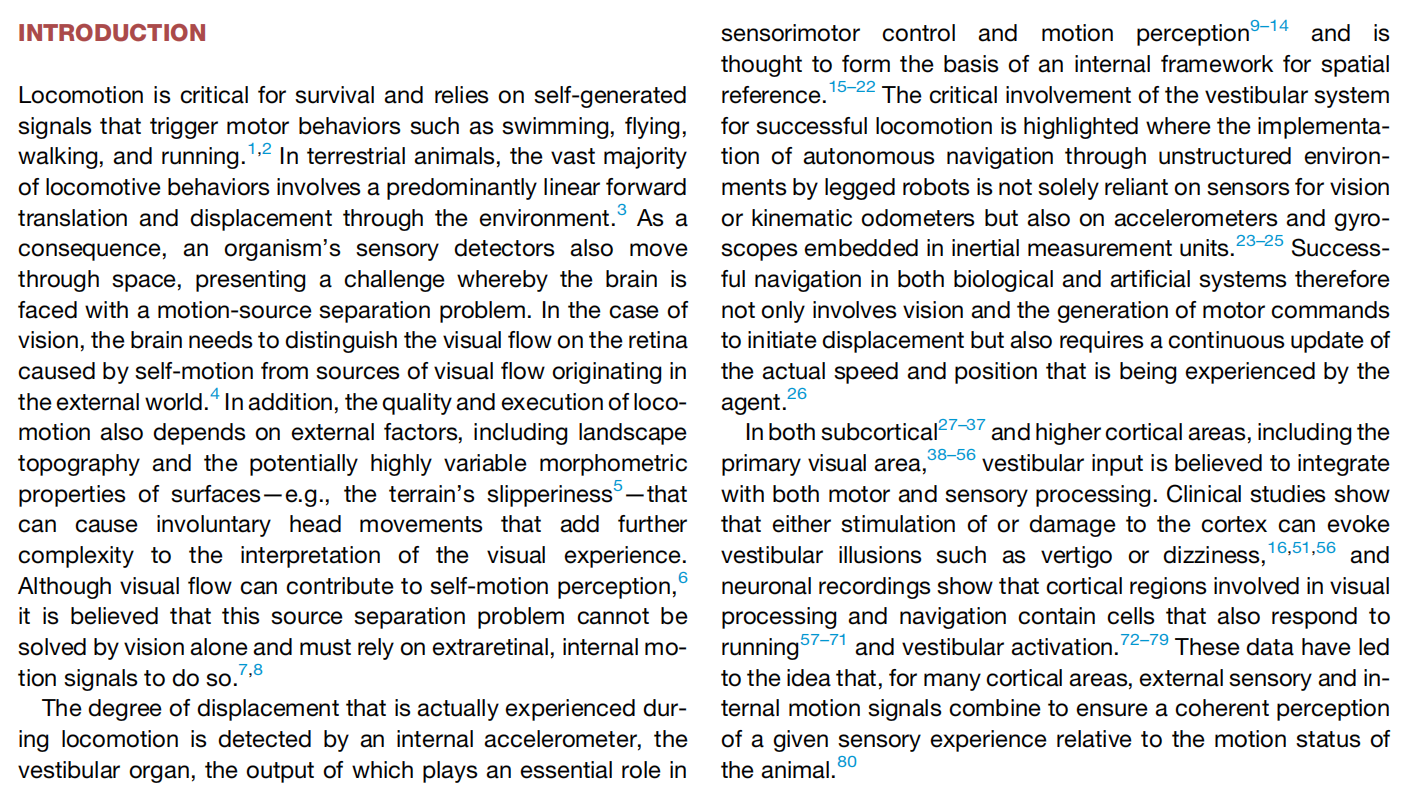

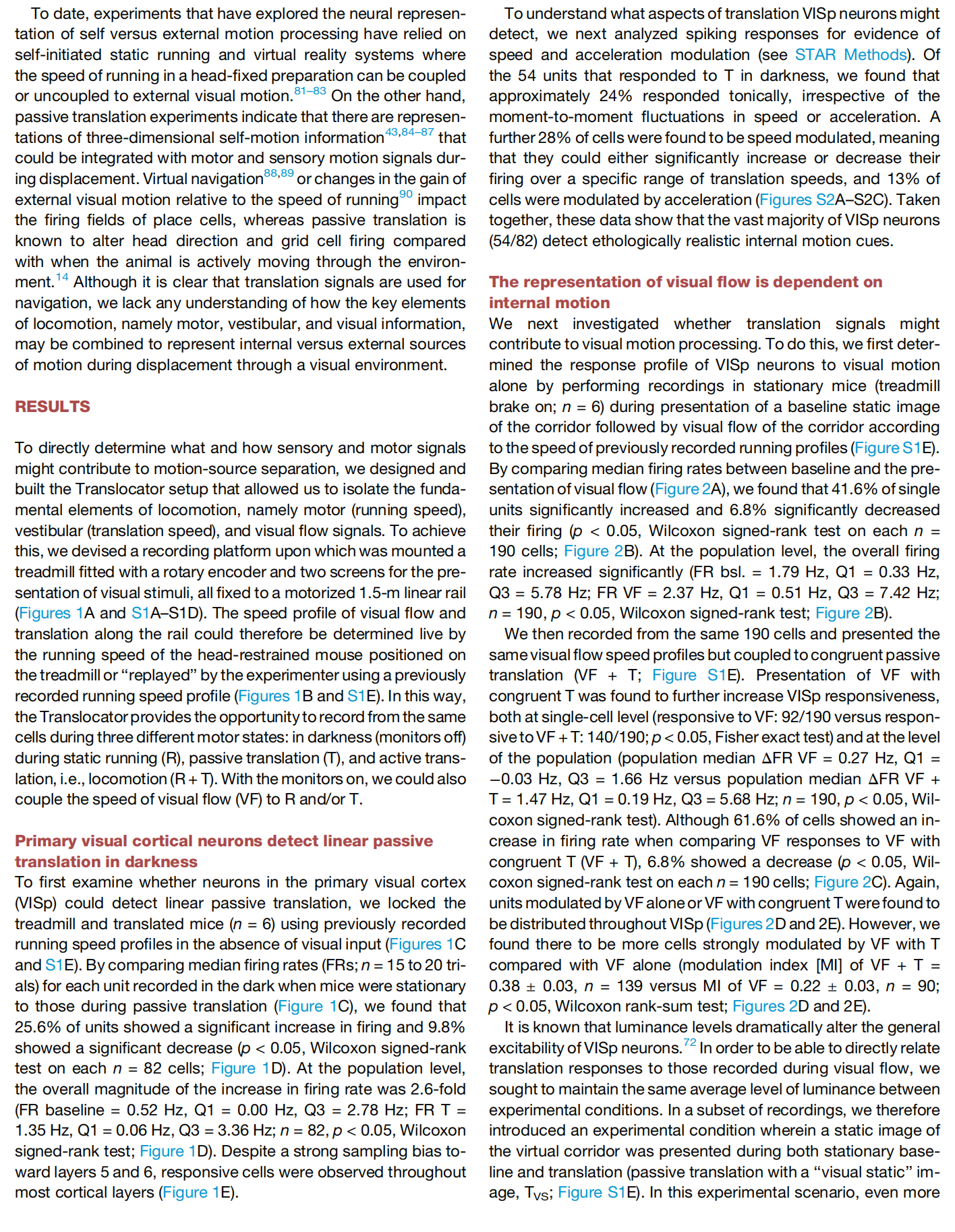

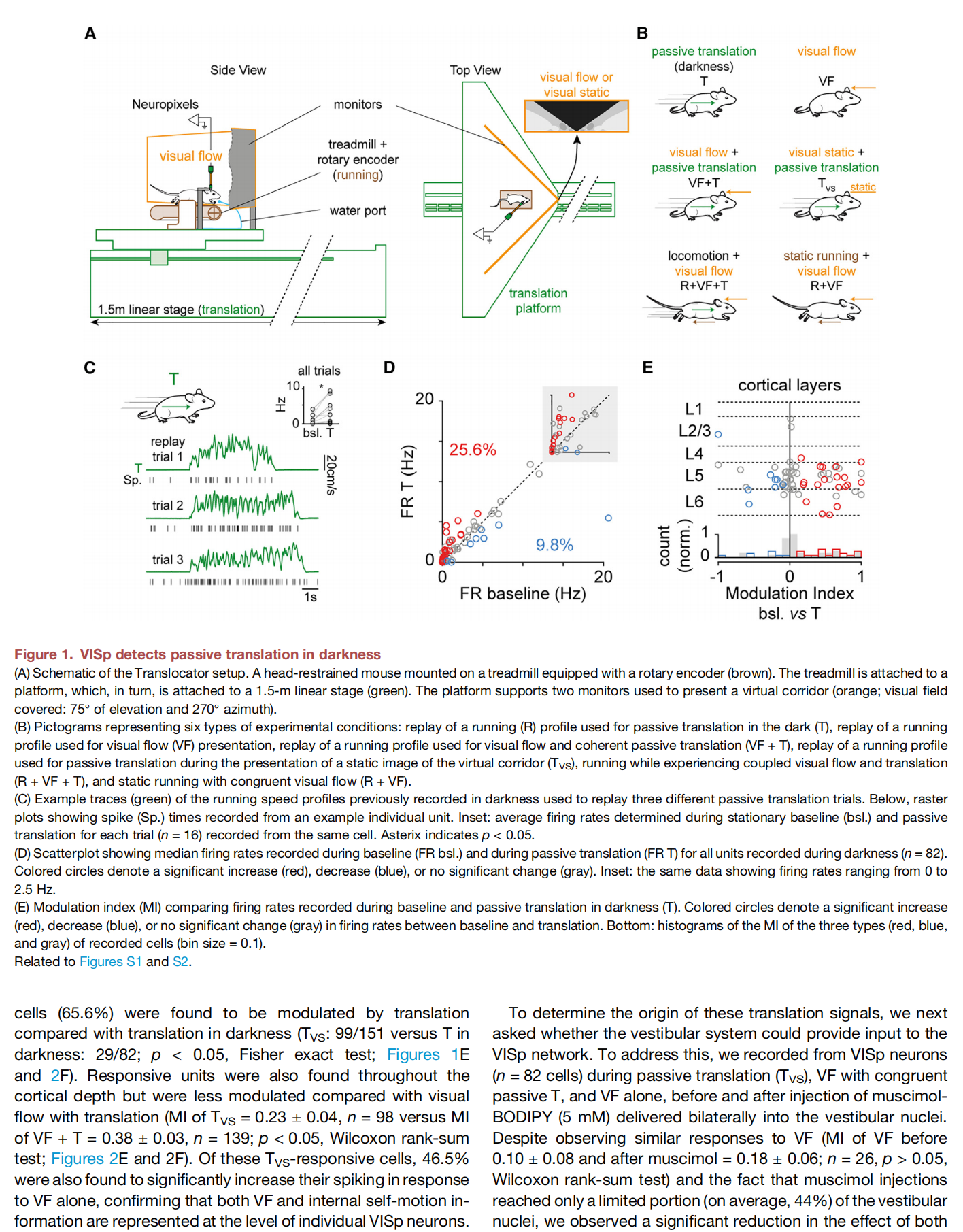

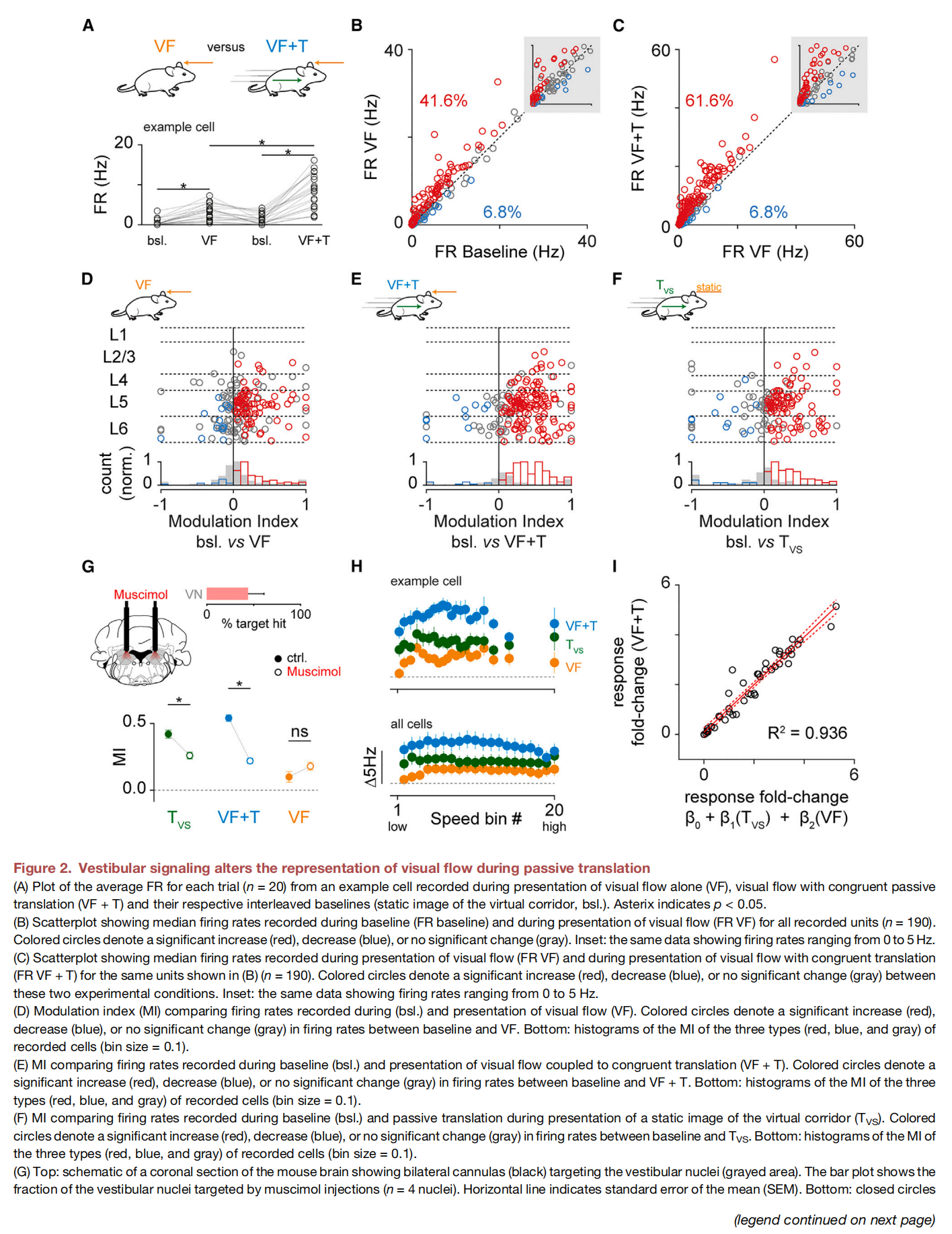

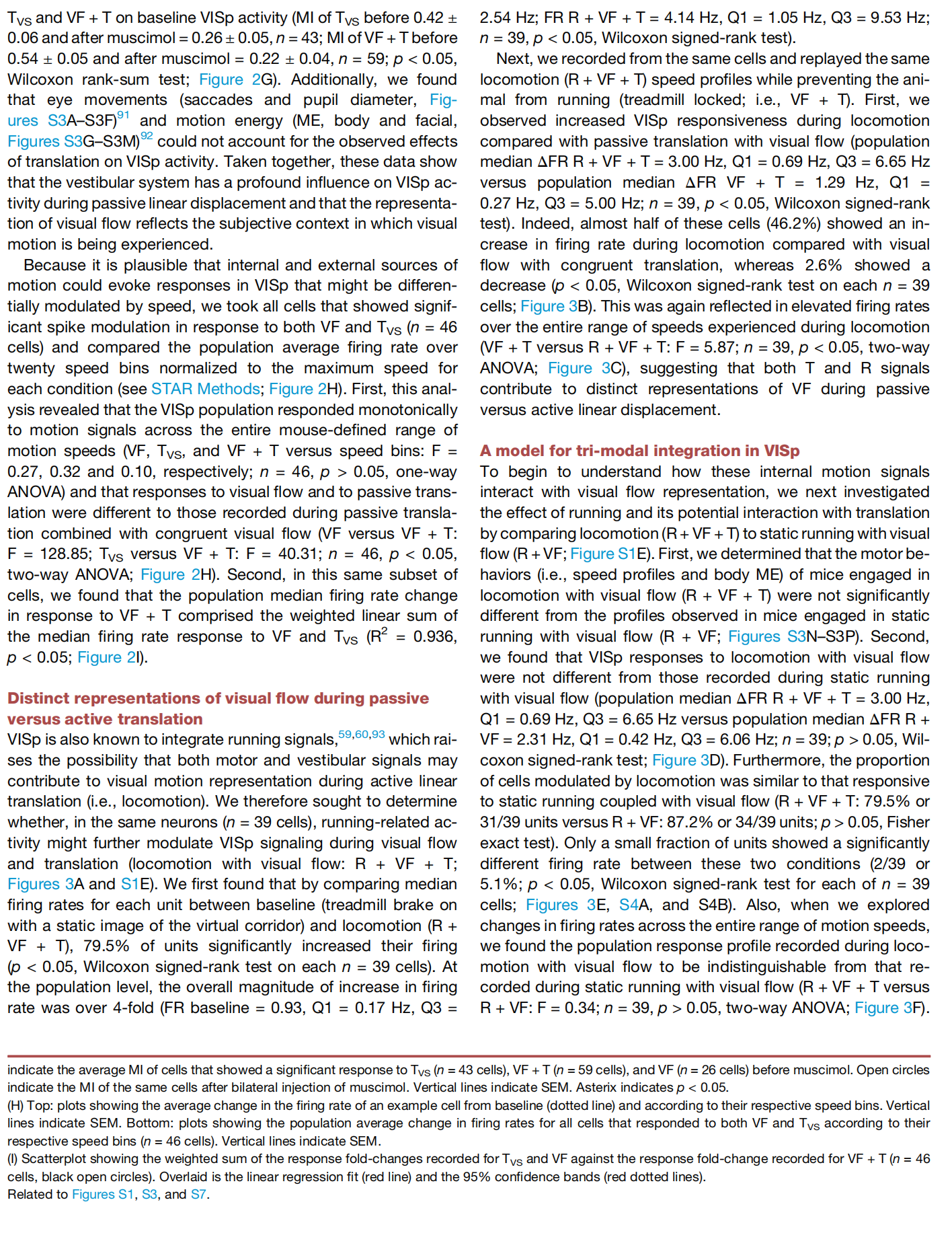

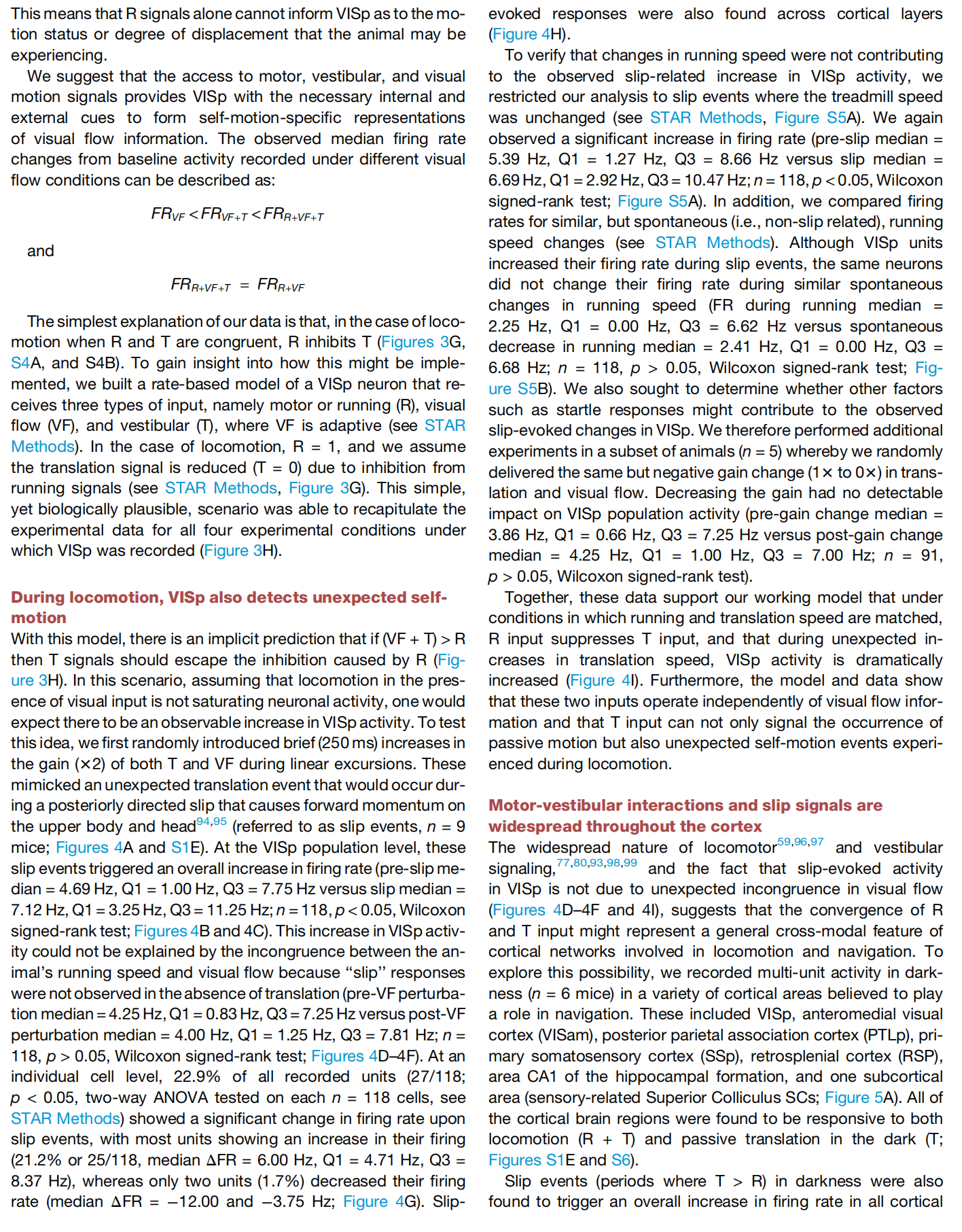

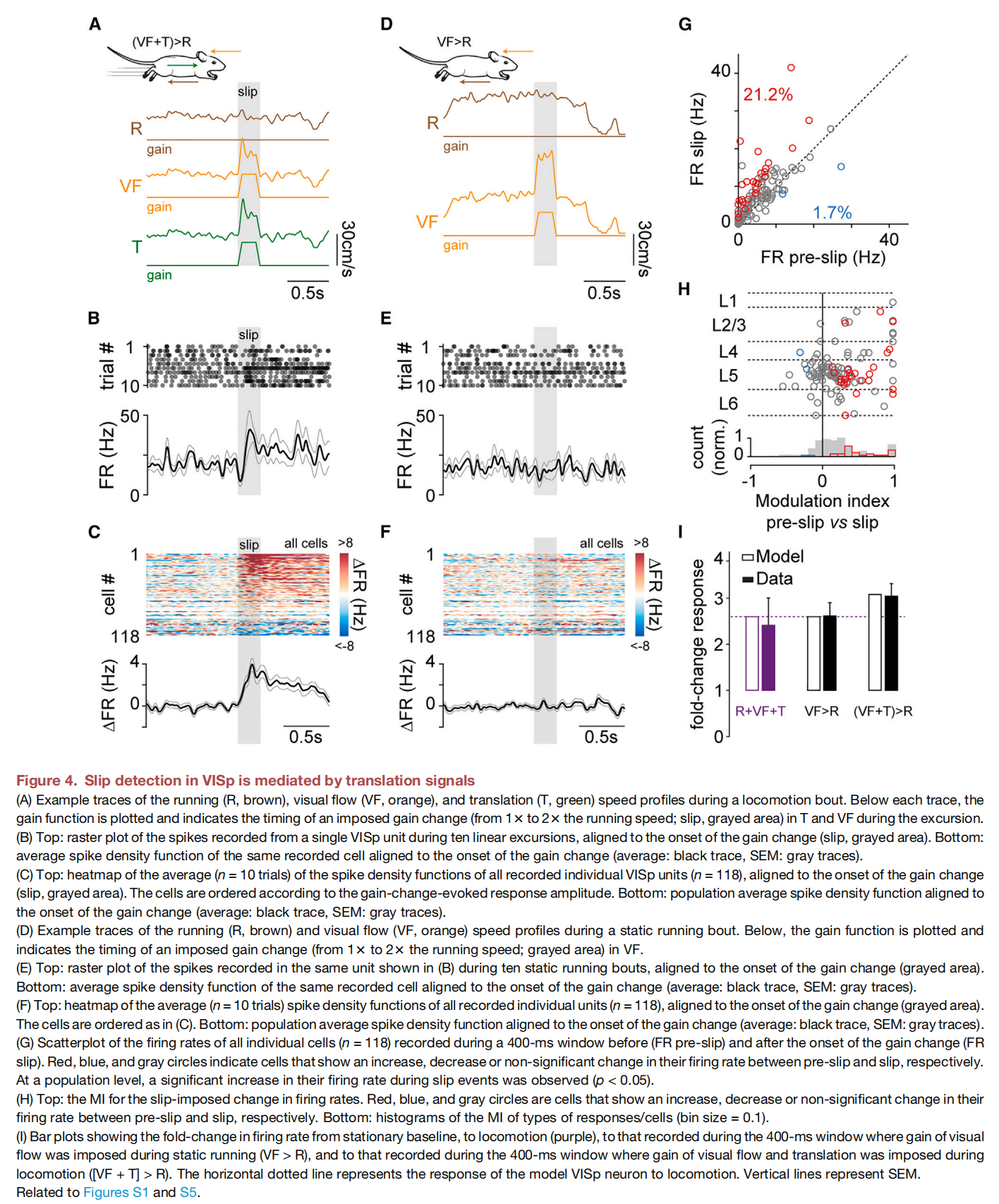

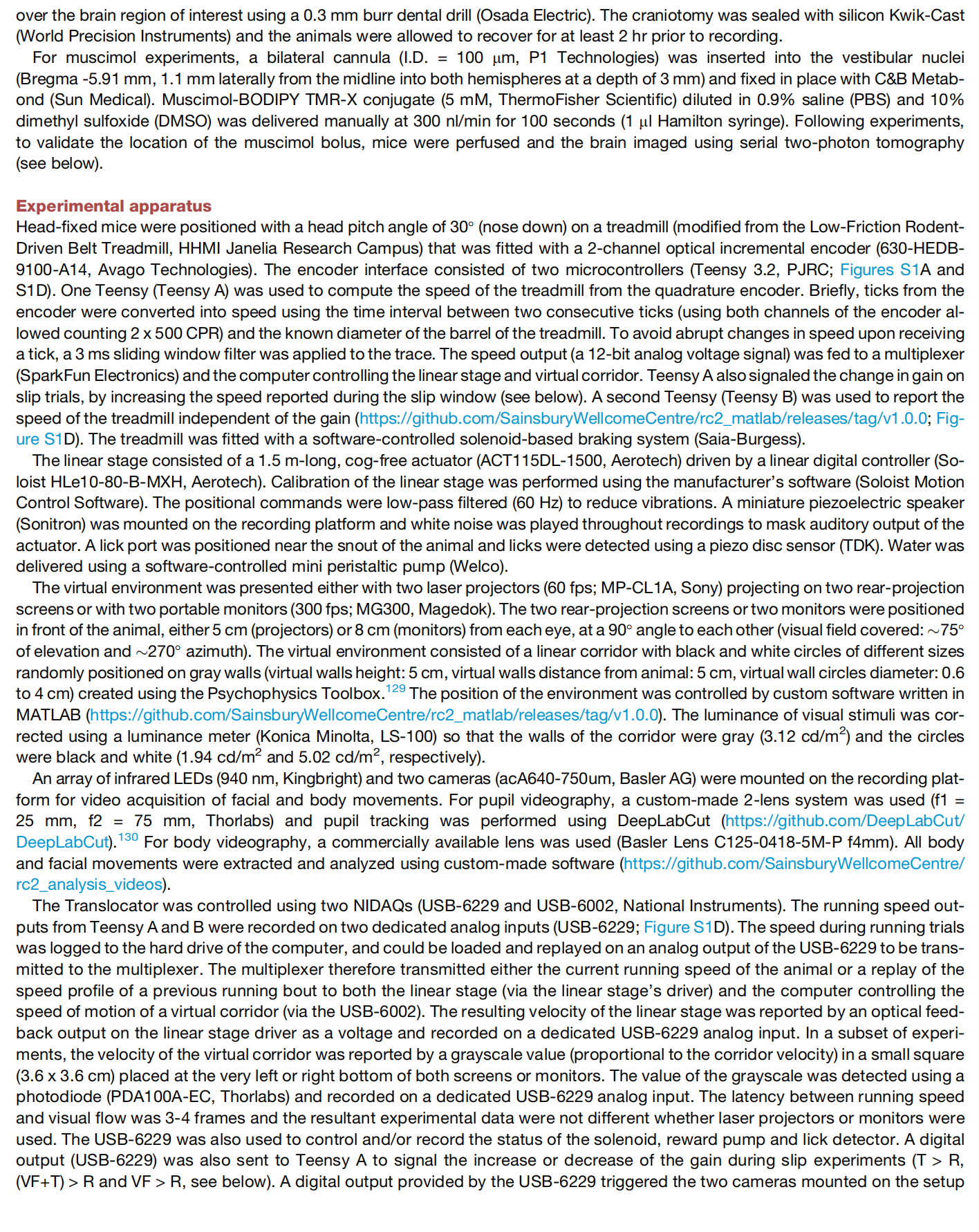

Knowing whether we are moving or something in the world is moving around us is possibly the most critical sensory discrimination we need to perform. How the brain and, in particular, the visual system solves this motion-source separation problem is not known. Here, we find that motor, vestibular, and visual motion signals are used by the mouse primary visual cortex (VISp) to differentially represent the same visual flow information according to whether the head is stationary or experiencing passive versus active translation. During locomotion, we find that running suppresses running-congruent translation input and that translation signals dominate VISp activity when running and translation speed become incongruent. This cross-modal interaction between the motor and vestibular systems was found throughout the cortex, indicating that running and translation signals provide a brain-wide egocentric reference frame for computing the internally generated and actual speed of self when moving through and sensing the external world.

This article is excerpted from the Cell 188, 2175–2189, April 17, 2025 by Wound World.