文献精选

Annemarie Wentzel1,2,3*, Arielle C. Patterson1 , M. Grace Duhuze Karera1,4,5, Zoe C. Waldman1 , Blayne R. Schenk1 , Christopher W. DuBose1 , Anne E. Sumner1,4 and Margrethe F. Horlyck-Romanovsky1,6*

1 Section on Ethnicity and Health, Diabetes, Endocrinology, and Obesity Branch, National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, United States,

2 Hypertension in Africa Research Team, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa, 3South African Medical Research Council, Unit for Hypertension and Cardiovascular Disease, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa, 4National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, United States, 5 Institute of Global Health Equity Research, University of Global Health Equity, Kigali, Rwanda, 6Department of Health and Nutrition Sciences, Brooklyn College, City University of New York, New York, NY, United States

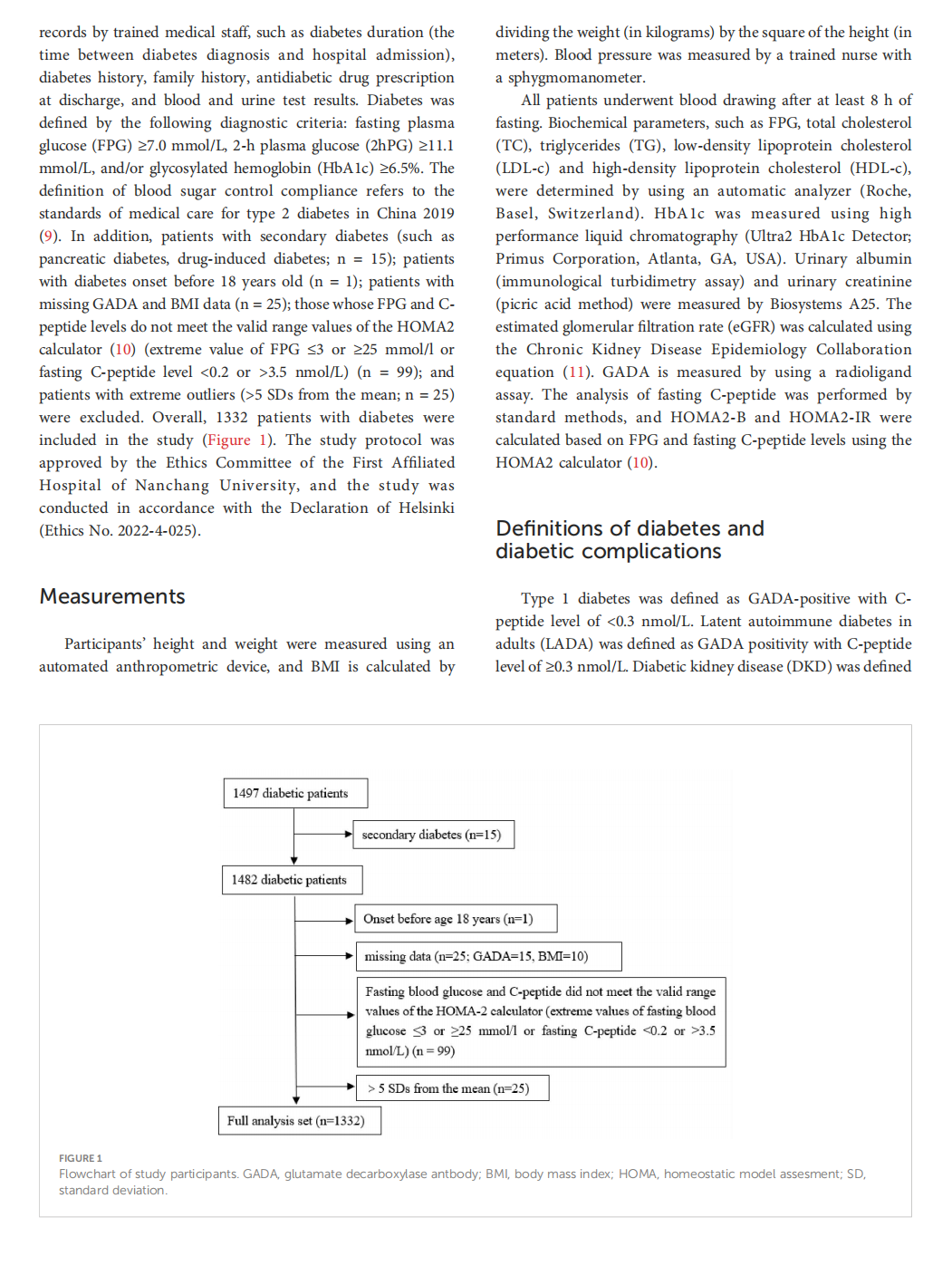

Background: Emerging data suggests that in sub-Saharan Africa β-cell-failure in the absence of obesity is a frequent cause of type 2 diabetes (diabetes). Traditional diabetes risk scores assume that obesity-linked insulin resistance is the primary cause of diabetes. Hence, it is unknown whether diabetes risk scores detect undiagnosed diabetes when the cause is β-cell-failure.

Aims: In 528 African-born Blacks living in the United States [age 38 ± 10 (Mean ± SE); 64% male; BMI 28 ± 5 kg/m2 ] we determined the: (1) prevalence of previously undiagnosed diabetes, (2) prevalence of diabetes due to β-cell-failure vs. insulin resistance; and (3) the ability of six diabetes risk scores [Cambridge, Finnish Diabetes Risk Score (FINDRISC), Kuwaiti, Omani, Rotterdam, and SUNSET] to detect previously undiagnosed diabetes due to either β-cell-failure or insulin resistance.

Methods: Diabetes was diagnosed by glucose criteria of the OGTT and/or HbA1c ≥ 6.5%. Insulin resistance was defined by the lowest quartile of the Matsuda index (≤2.04). Diabetes due to β-cell-failure required diagnosis of diabetes in the absence of insulin resistance. Demographics, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, visceral adipose tissue (VAT), family medical history, smoking status, blood pressure, antihypertensive medication, and blood lipid profiles were obtained. Area under the Receiver Operator Characteristics Curve (AROC) estimated sensitivity and specificity of each continuous score. AROC criteria were: Outstanding: >0.90; Excellent: 0.80–0.89; Acceptable: 0.70–0.79; Poor: 0.50–0.69; and No Discrimination: 0.50.

Results: Prevalence of diabetes was 9% (46/528). Of the diabetes cases, β-cell-failure occurred in 43% (20/46) and insulin resistance in 57% (26/46). The β-cell-failure group had lower BMI (27 ± 4 vs. 31 ± 5 kg/m2 P < 0.001), lower waist circumference (91 ± 10 vs. 101 ± 10cm P < 0.001) and lower VAT (119 ± 65 vs. 183 ± 63 cm3 , P < 0.001). Scores had indiscriminate or poor detection of diabetes due to β-cell-failure (FINDRISC AROC = 0.49 to Cambridge AROC = 0.62). Scores showed poor to excellent detection of diabetes due to insulin resistance, (Cambridge AROC = 0.69, to Kuwaiti AROC = 0.81).

Conclusions: At a prevalence of 43%, β-cell-failure accounted for nearly half of the cases of diabetes. All six diabetes risk scores failed to detect previously undiagnosed diabetes due to β-cell-failure while effectively identifyingdiabetes when the etiology was insulin resistance. Diabetes risk scores whichcorrectly classify diabetes due to B-cell-failure are urgently needed.

KEYWORDS

type 2 diabetes, risk score, African (Black) diaspora, β-cell failure, insulin resistance, diabetes screening

Wang Shuaishuai 1† , Zhu Tongtong1† , Wang Dapeng2 ,

Zhang Mingran1 , Wang Xukai 1 , Yu Yue1 , Dong Hengliang1 ,

Wu Guangzhi 1 * and Zhang Minglei 1 *

1 Department of Orthopedics, China-Japan Union Hospital of Jilin University, Changchun, China,

2 Department of Orthopedics, Siping Central Hospital, Siping, China

EDITED BY

Xiaoyuan Li,

Northeast Normal University, China

REVIEWED BY

Fuzeng Ren,

Southern University of Science and

Technology, China

Gong Cheng,

Harvard University, United States

Ruogu Qi,

Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine,

China

*CORRESPONDENCE

Wu Guangzhi,

该Email地址已收到反垃圾邮件插件保护。要显示它您需要在浏览器中启用JavaScript。

Zhang Minglei,

该Email地址已收到反垃圾邮件插件保护。要显示它您需要在浏览器中启用JavaScript。

†

These authors have contributed equally to this work

SPECIALTY SECTION

This article was submitted to Biomaterials, a section of the journal

Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology

RECEIVED 27 October 2022

ACCEPTED 18 January 2023

PUBLISHED 30 January 2023

CITATION

Shuaishuai W, Tongtong Z, Dapeng W, Mingran Z, Xukai W, Yue Y, Hengliang D, Guangzhi W and Minglei Z (2023), Implantable biomedical materials for treatment of bone infection.

Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 11:1081446.

doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2023.1081446

COPYRIGHT

© 2023 Shuaishuai, Tongtong, Dapeng, Mingran, Xukai, Yue, Hengliang, Guangzhi and Minglei. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY).

The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

The treatment of bone infections has always been difficult. The emergence of drugresistant bacteria has led to a steady decline in the effectiveness of antibiotics. It is also especially important to fight bacterial infections while repairing bone deffects and cleaning up dead bacteria to prevent biofilm formation. The development of biomedical materials has provided us with a research direction to address this issue.

We aimed to review the current literature, and have summarized multifunctional antimicrobial materials that have long-lasting antimicrobial capabilities that promote angiogenesis, bone production, or “killing and releasing.” This review provides a comprehensive summary of the use of biomedical materials in the treatment of bone infections and a reference thereof, as well as encouragement to perform further research in this field.

KEYWORDS

biological materials, bone infection, multifunctional material, implantable material, treatment of bone infection, progress of infection treatment, multifunctionalization of materials

This article is excerpted from the 《 Frontiers in Endocrinology》 by Wound World

This article is excerpted from the 《Frontiers in Psychology》 by Wound World