Pimpa Tantanasrigul1 | Apinya Sripha1 | Bunchai Chongmelaxme21

Department of Medical Services, Ministry of Public Health, Institute of Dermatology, Bangkok, Thailand | 2Department of Social and Administrative Pharmacy, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand

Correspondence: Bunchai Chongmelaxme (该Email地址已收到反垃圾邮件插件保护。要显示它您需要在浏览器中启用JavaScript。)

Received: 5 July 2024 | Accepted: 22 August 2024

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Keywords: alpha-arbutin 5% | efficacy | kojic acid 2% | melasma | safety | triple combination cream

ABSTRACT

Background: While the gold standard treatment for melasma is triple combination cream (TCC), arbutin and kojic acid demonstrate their benefits and may be used as an alternative.

Aims: To investigate the efficacy of cream containing alpha-arbutin 5% and kojic acid 2% (AAK) compared with TCC for melasma treatment.

Patients/Methods: A split-faced, randomized study was conducted among 30 participants with melasma, and all were randomized to receive AAK or TCC on each side of their face for 12-week along with 4-week follow-up period. The melanin index (MI), modified Melasma Area Severity Index (mMASI), and physician global assessment (PGA) scores were used to measure the effectiveness of interventions. Recurrence of melasma after treatment discontinuation was evaluated by MI and mMASI. Patient satisfactions and adverse effects were also evaluated. In the analysis, the mean difference (MD) was used for MI and mMASI, while Wilcoxon signed-rank test was for the PGA scores, adverse effects, and patient satisfaction.

Results: The MD of MI and mMASI scores were not different between groups (mMASI [p=0.344] and MI [p=0.268]). The PGA scores only showed improvement on the TCC-treated side (p=0.032). Compared to the AKK group, the subjects with TCC showed higher severity of recurrence (MI [p=0.004] and mMASI [p=0.045]). No difference in patient satisfaction score between the groups, but erythema and stinging were higher in the TCC group.

Conclusions: The AAK cream appeared to be effective for melasma treatment, highlighting a lower recurrent rate and fewer adverse events than standard therapy.

Trial Registration: thaiclinicaltrials.org: TCTR20230124004

This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

© 2024 The Author(s). Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology published by Wiley Periodicals LLC.

A qualitative exploration of the prospective acceptability of the MiDerm app; a complex digital intervention for adults living with skin conditions

Rachael M. Hewitt1 | Carys Dale1 | Catherine Purcell1 | Rachael Pattinson2 | Chris Bundy1

1 School of Healthcare Sciences, Cardiff University, Wales, UK

2 School of Dentistry, Cardiff University, Wales, UK

Correspondence

Rachael M. Hewitt, School of Healthcare Sciences, Cardiff University, Heath Park Campus, Cardiff, CF14 4XN, UK.

Email: 该Email地址已收到反垃圾邮件插件保护。要显示它您需要在浏览器中启用JavaScript。

Funding information

Beiersdorf

Abstract

Objectives: Skin conditions carry a substantial psychological burden but support for patients is limited. Digital technology could support patient self-management; we found preliminary evidence for the effectiveness and acceptability of digital psychological interventions for adults living with skin conditions. We have, therefore, developed a complex digital intervention called MiDerm with patients. This qualitative study explored the prospective acceptability of the complex intervention delivered via a smartphone application (app), and possible barriers and facilitators to use.

Design: Qualitative research involving a hybrid inductivedeductive approach. Data collection and analysis were theoretically informed by The Common-Sense Model of SelfRegulation, Theoretical Framework of Acceptability and the Capability, Opportunity, Motivation - Behaviour Model.

Methods: Eight synchronous online group interviews with 43 English-speaking adults (≥18 years) with skin conditions. Data were analysed using Reflexive Thematic Analysis.

Results: Three superordinate themes were generated: (1) Patients' attitudes and concerns about the MiDerm app; (2) Need for personal competence, autonomy and relatedness for effective self-management; and (3) Physical, psychological and social barriers to app use.

Conclusion: Adults with skin conditions, mainly those with vitiligo and psoriasis living in the UK, expressed the need for support to self-manage the psychological aspects of their condition(s). The idea of a new intervention comprised of informational, emotional, behavioural and peer support, delivered via a smartphone app was welcomed and may be especially beneficial for specific patients. Identified barriers must be addressed to maximize engagement and giving users choice, flexibility and control is imperative to this. We have since developed the MiDerm app using these findings.

KEYWORDS

dermatology, digital intervention, qualitative research

A comprehensive classification and analysis of oily sensitive facial skin: a cross-sectional study of young Chinese women

Xinjue Kuang1,2, Caini Lin1,2, Yuanyuan Fu3, YuhuiWang3, JunhuaGong3, Yong Chen3,4, Youting Liu3,4,6 & FanYi1,2,5

1 Key Laboratory of Cosmetic, China National Light Industry, Beijing Technology and Business University, Beijing,China.

2Institute of Cosmetic Regulatory Science, Beijing Technology and Business University, Beijing, China.

3 Beijing Uproven Medical Technology Co. LTD, Beijing, China.

4 Beijing Uproven Institute of Dermatology, Beijing,China.

5 Beijing Technology and Business University, No.11/33, Fucheng Road, Haidian District, Beijing 100048,China.

6 Beijing Uproven Institute of Dermatology, Room 1109, 11th Floor, Building 13, No. 5 Tianhua Street, Daxing District, Beijing 102600, China. email: 该Email地址已收到反垃圾邮件插件保护。要显示它您需要在浏览器中启用JavaScript。; 该Email地址已收到反垃圾邮件插件保护。要显示它您需要在浏览器中启用JavaScript。

Oily sensitive skin is complex and requires accurate identification and personalized care. However, the current classification method relies on subjective assessment. This study aimed to classify skin type and subtype using objective biophysical parameters to investigate differences in skin characteristics across anatomical and morphological regions. This study involved 200 Chinese women aged 17–34 years. Noninvasive capture of biophysical measures and image analysis yielded 104 parameters. Key classification parameters were identified through mechanisms and characteristics, with thresholds set via statistical methods. This study identified the optimal ternary value classification method for dividing skin types into dry, neutral, and oily types based on tertiles of biophysical parameters and, further, into barrier-sensitive, neurosensitive, and inflammatory-sensitive types. Oily sensitive skin shows increased sebum, follicular orifices, redness, dullness, wrinkles, and porphyrins, along with a tendency for oiliness and early acne. Subtypes exhibited specific characteristics: barrier-sensitive skin was rough with a high pH and prone to acne; neurosensitive skin had increased TEWL (Transepidermal Water Loss) and sensitivity; and inflammatory-sensitive skin exhibited a darker tone, with low elasticity and uneven redness. This study established an objective classification system for skin types and subtypes using noninvasive parameters, clarifying the need for care for oily sensitive skin and supporting personalized skincare.

Keywords Oily sensitive skin, Noninvasive biophysical testing, Skin classification, Sensitivity subtypes, Personalized skincare

Does the point of healthcare contact affect successful diagnosis of diabetic Charcot neuroarthropathy?

Amy Sherratt, Jennie Hancox, Frances Game and Katie Gray

Citation: Sherratt A, Hancox J, Game F, Gray K (2024) Does the point-of-healthcare contact affect successful diagnosis of diabetic Charcot neuroarthropathy? The Diabetic Foot Journal 27(2): 44–8

Key words

- Charcot

- Diabetes

- Delay

- Foot

- Misdiagnosis

Article points

1. Delays in diagnosis increase the risk of severe long-term foot complications

2. A retrospective audit of patients with active Charcot neuroarthropathy examined the time to diagnosis, misdiagnosis rates, healthcare professional (HCP) and setting type at each contact, since symptom onset prior to their referral to a multidisciplinary foot team (MDFT) clinic

3. Results showed that non-specialist HCPs require a greater degree of awareness and understanding of Charcot neuroarthropathy to reduce diagnostic delays and misdiagnosis rates.

Authors

Amy Sherratt is a Diabetes Specialist and Research Podiatrist, University Hospitals of Derby and Burton & Derbyshire Community Health Services, Derbyshire; Jennie Hancox is a Lecturer at Loughborough University, School of Sport, Exercise and Health Sciences; Frances Game is a Consultant Diabetologist and Director of Research and Development, University Hospitals of Derby and Burton, Derbyshire and Katie Gray is a Diabetes Specialist and Research Podiatrist, University Hospitals of Derby and Burton & Derbyshire Community Health Services, Derbyshire.

Background: Charcot neuroarthropathy (CN) is a lesser-known and commonly misdiagnosed diabetic foot complication. Delays in diagnosis increase the risk of severe long-term foot complications. Aims: To undertake a retrospective audit of patients with active CN, recording the time to diagnosis, misdiagnosis rates, healthcare professional (HCP) and setting type at each contact since symptom onset prior to their referral to a multidisciplinary foot team (MDFT) clinic in a circumscribed part of England. Methods: Clinical notes of 46 consecutive patients attending a MDFT clinic in the East Midlands region of England during a 2-month period, with active CN were assessed. Results: Of the 46 included patients, 22 developed CN while in primary care. These patients had a mean time from symptom onset to confirmed diagnosis of 68 days, with 64% receiving a misdiagnosis. Non-specialist HCPs failed to suspect CN in 85% of contacts compared to 20% in specialist HCPs. Conclusions: Non-specialist HCPs need a greater degree of awareness and understanding of CN to reduce diagnostic delays and misdiagnosis rates.

中国老年糖尿病诊疗指南(2024版)---16~完结

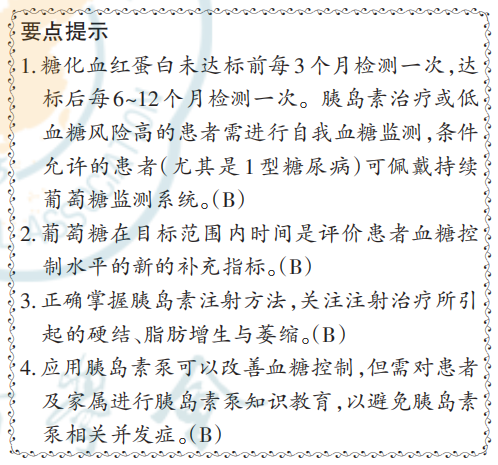

第十六章 糖尿病管理相关技术

一、血糖监测

血糖监测技术包括自我血糖监测、CCM、糖化白蛋白和HbA1c等。

HbA1c是临床上用以评价长期血糖控制状况的金标准,是调整治疗方案的重要依据。对于HbA.未达标的患者,建议每3个月检测一次。一旦达标后,可每6~12个月检测一次。但 HbA,也存在一定的局限性,如难以反映血糖波动,无法捕捉低血糖事件等。建议胰岛素治疗的老年糖尿病患者进行自我血糖监测,基本监测点为空腹和三餐前,以了解患者的血糖基线水平,如患者存在夜间低血糖风险,建议根据情况加测睡前和夜间血糖,对于口服降糖药治疗且血糖控制平稳的患者无需频繁监测血糖。

在老年糖尿病患者中,佩戴 CGM 能进一步改善HbA1c,同时降低血糖变异性,而不增加低血糖风险[321‑322] 。T1DM 患者胰岛功能差、血糖波动大,更可能从CGM中获益。建议临床医师结合患者的血糖情况、认知水平、行动能力、经济情况等进行综合评估后提出是否佩戴CGM的建议。在使用基础胰岛素的老年T2DM患者中,使用CGM的患者较传统指血检测的患者 TIR 增加,其获益与年轻患者一致[323] 。

TIR 是指 24 h 内葡萄糖在目标范围的时长或所占的百分比,成人糖尿病患者中TIR的血糖范围一般界定为3.9~10.0 mmol/L,但尚缺乏针对老年糖尿病患者的研究。近年来国际共识推荐 TIR 可作为成人 T1DM 和 T2DM 血糖控制情况的评价指标,同时 TBR和 TAR也可以作为评价治疗方案的有效参数。我国的研究表明,在 T2DM 中 TIR 独立于HbA1c与糖尿病微血管并发症相关(患者平均年龄60.4岁)[324] ,与心血管死亡、全因死亡相关(患者平均年龄 61.7 岁)[325] 。在老年糖尿病的管理中,TIR也可以作为评价血糖控制水平的补充指标,但尚需针对老年糖尿病患者的研究证实。TIR 目标的确定需考虑老年糖尿病患者的个体化差异和低血糖风险,并有待进一步的循证医学证据明确。研究显示,在 T1DM 中 TIR 与 TAR 相关性强,但与 TBR 相关性弱,对于使用自动胰岛素给药系统的老年患者,应优先考虑降低 TBR 以减少低血糖风险[326] 。除了影响血糖控制外,CGM 对老年糖尿病还具有其他获益,例如患者可以与家人或其他照护者持续分享血糖结果;减少指血血糖检测次数,尤其是对于有身体残疾、认知障碍或视力障碍的患者;对于低血糖觉察能力降低或受损的患者,CGM 可以帮助患者觉察低血糖[327] 。

二、注射技术

正确的皮下胰岛素注射技术包括每次注射后更换针头、选择合适的部位注射、轮换注射的部位、适当护理注射部位以及避免肌肉注射。推荐注射部位包括腹部、大腿、臀部和上臂。长期在同一部位进行 注射可能导致局部脂肪肥大或脂肪萎缩[328],需定期并轮替变换注射部位 。 中国 ITIMPROVE 研究对中国糖尿病患者、医师和护士的问卷调查显示,34.7% 患者出现注射部位脂肪增生,针头重复使用以及注射部位轮换不当可分别使脂肪增生风险增加 3.15 倍和 1.27 倍,同时也增加HbA1c达标的风险[329] 。

老年糖尿病患者如果存在痴呆、视力丧失、神经病变、活动能力差、手指灵活性差等情况,在进行胰岛素注射时出现遗漏注射、错误注射的风险增加,医师也无法准确了解患者胰岛素的实际注射情况。随着胰岛素注射笔的不断改良,更多的功能已被开发并应用。记忆功能可记录上次胰岛素注射的剂量和注射时间,帮助提高胰岛素治疗的依从性[330] 。依托具有可连接功能、支持近距离无线通信的手机等智能设备进行连接,可以将胰岛素注射记录传输到智能手机等设备并通过应用程序生成可视化注册日志并分享。一项前瞻性临床研究提示,可连接胰岛素笔能显著减少43%的胰岛素注射遗漏,提高TIR,降低TAR和TBR[331] 。

无针注射技术是《中国糖尿病药物注射技术指南》推荐的注射方法之一,能缓解患者对传统有针注射笔的恐针心理,降低注射痛感,从而提高患者依从性,改善血糖控制[332] 。此外,无针注射可减少有针注射相关的不良反应,如皮下硬结、脂肪增生或萎缩,并减少了胰岛素的用量。有条件时可用于健康状态为良好(Group 1)和中等(Group 2)的老年糖尿病患者。但无针注射的操作相较于胰岛素笔注射复杂,需经专业人员指导,熟练掌握操作方法后方可自行注射。对于无法自行完成注射操作的患者,需教育患者家属积极协助或选用其他的注射方式。

三、胰岛素泵

胰岛素泵是采用人工智能控制的胰岛素输送装置,可以连续进行皮下胰岛素注射,最大程度模拟胰岛素的生理分泌,以帮助管理血糖。对于老年糖尿病患者,尤其是 T1DM,如采用多针胰岛素皮下注射治疗血糖波动大、低血糖风险高,建议试用胰岛素泵。采用多针胰岛素皮下注射难以精确调整胰岛素用量的患者也可考虑应用胰岛素泵。在老年 T2DM 患者中,有研究提示,相较于多针胰岛素皮下注射,使用胰岛素泵可以有效控制血糖,安全性和患者满意度良好[333] 。有研究证实在平均年龄大于 60 岁的 T2DM 患者中应用自动胰岛素输注系统的安全性和有效性[334] 。认知能力下降、视力下降、手指灵活性下降、无他人协助、缺乏胰岛素泵的知识等均可能是老年糖尿病患者使用胰岛素泵的限制因素[335] 。临床医师需结合患者的个体情况决定是否采用胰岛素泵治疗,并对患者及家属进行胰岛素泵知识的充分教育,包括胰岛素泵的设置、报警的处理、潜在的并发症等。应建立良好的协助模式,在患者的胰岛素泵需要调整时能被快速有效地处理,以免出现胰岛素泵相关的急性不良事件。

第十七章 老年糖尿病与中医药学

糖尿病属中医“消渴病”范畴,我国传统医学治疗历史由来已久。中医认为,糖尿病的基本病机为阴虚燥热,因具有口干多饮、多食易饥、小便频数的临床特点,分别涉及肺、胃、肾等病位,其治疗相应可分上、中、下三消论治。中医药在糖尿病及其并发症的治疗中有一定效果。由于老年患者常伴器官功能衰退,多种并发症和合并症并存,中西药物使用情况复杂等多重因素,因此,需要在专业中医指导下接受中医、中西医结合治疗,并且在治疗过程中注意用药的安全性。

执笔者:

潘 琦(北京医院内分泌科 国家老年医学中心)

邓明群(北京医院内分泌科 国家老年医学中心)

虞睿琪(中国医学科学院北京协和医院内分泌科)

专家委员会名单(按照姓氏拼音排序):

陈 宏(南方医科大学珠江医院内分泌科)

陈 丽(山东大学齐鲁医院内分泌科)

陈莉明(天津医科大学朱宪彝纪念医院内分泌科)

陈有信(中国医学科学院北京协和医院眼科)

窦京涛(解放军总医院第一医学中心内分泌科)

杜建玲(大连医科大学附属第一医院内分泌科)

段滨红(黑龙江省医院内分泌科)

郭立新(北京医院内分泌科 国家老年医学中心)

洪天配(北京大学第三医院内分泌科)

侯新国(山东大学齐鲁医院内分泌科)

胡 吉(苏州大学附属第二医院内分泌科)

姬秋和(空军军医大学西京医院内分泌科)

纪立农(北京大学人民医院内分泌科)

姜 昕(深圳市人民医院老年病科)

蒋 升(新疆医科大学第一附属医院内分泌科)

康 琳(中国医学科学院北京协和医院老年医学科)

匡洪宇(哈尔滨医科大学附属第一医院内分泌科)

邝 建(广东省人民医院内分泌科)

雷闽湘(中南大学湘雅医院内分泌科)

李春霖(解放军总医院第二医学中心内分泌科)

李全民(火箭军特色医学中心内分泌科)

李 兴(山西医科大学第二医院内分泌科)

李延峰(中国医学科学院北京协和医院神经内科)

李益明(复旦大学附属华山医院内分泌科)

李 勇(复旦大学附属华山医院心血管内科)

梁瑜祯(广西医科大学第二附属医院内分泌科)

林夏鸿(中山大学附属第七医院内分泌科)

刘 静(甘肃省人民医院内分泌科)

刘幼硕(中南大学湘雅二医院老年医学科)

鹿 斌(复旦大学附属华东医院内分泌科)

陆颖理(上海交通大学医学院附属第九人民医院内分泌科)

吕文山(青岛大学附属医院内分泌科)

母义明(解放军总医院第一医学中心内分泌科)

潘 琦(北京医院内分泌科 国家老年医学中心)

秦贵军(郑州大学第一附属医院内分泌科)

沈云峰(南昌大学第二附属医院内分泌科)

施 红(北京医院老年医学科 国家老年医学中心)

宋光耀(河北省人民医院内分泌科)

童南伟(四川大学华西医院内分泌科)

王建业(北京医院泌尿外科 国家老年医学中心 中国医学科学院老

年医学研究院)

王世东(北京中医药大学东直门医院内分泌科)

王颜刚(青岛大学附属医院内分泌科)

王正珍(北京体育大学运动医学与康复学院)

吴 静(中南大学湘雅医院内分泌科)

吴天凤(浙江医院内分泌科)

武晓泓(浙江省人民医院内分泌科)

肖建中(清华大学附属北京清华长庚医院内分泌科)

肖新华(中国医学科学院北京协和医院内分泌科)

谢晓敏(银川市第一人民医院内分泌科)

徐 静(西安交通大学第二附属医院内分泌科)

徐向进(解放军联勤保障部队第九〇〇医院内分泌科)

徐焱成(武汉大学中南医院内分泌科)

徐 勇(西南医科大学附属医院内分泌科)

徐玉善(昆明医科大学第一附属医院内分泌科)

许樟荣(解放军战略支援部队特色医学中心内分泌科)

薛耀明(南方医科大学第一临床医学院南方医院内分泌科)

杨 川(中山大学孙逸仙纪念医院内分泌科)

杨 静(山西医科大学第一医院内分泌科)

杨 涛(南京医科大学第一附属医院内分泌科)

杨 莹(云南大学附属医院内分泌科)

余学锋(华中科技大学同济医学院附属同济医院内分泌科)

袁慧娟(河南省人民医院内分泌科)

张 波(中日友好医院内分泌科)

张存泰(华中科技大学同济医学院附属同济医院老年医学科)

张俊清(北京大学第一医院内分泌科)

章 秋(安徽医科大学第一附属医院内分泌科)

赵家军(山东第一医科大学附属省立医院内分泌科)

利益冲突 所有作者声明无利益冲突

参 考 文 献

[1] 中华人民共和国民政部 . 2021 年民政事业发展统计公报 [EB/OL]. (2022‑08‑26) [2023‑11‑01]. https://www. mca.gov.cn/n156/n189/index.html.

[2] LeRoith D, Biessels GJ, Braithwaite SS, et al. Treatment of diabetes in older adults: an Endocrine Society* clinical practice guideline[J]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2019,

104(5):1520‑1574. DOI: 10.1210/jc.2019‑00198.

[3] 国务院办公厅 . 中国防治慢性病中长期规划(2017—2025 年) [EB/OL]. (2017‑02‑14) [2023‑11‑01]. https://www.forestry.gov.cn/c/www/gwywj/56699.jhtml.

[4] 国家老年医学中心, 中华医学会老年医学分会, 中国老年保健协会糖尿病专业委员会 . 中国老年糖尿病诊疗指南(2021 年版)[J]. 中华糖尿病杂志, 2021, 13(1):14‑46. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.cn115791‑20201209‑00707.

[5] 中国老年 2型糖尿病防治临床指南编写组, 中国老年医学学会老年内分泌代谢分会, 中国老年保健医学研究会老年内分泌与代谢分会, 等. 中国老年2型糖尿病防治临床指南(2022 年版) [J]. 中华内科杂志, 2022, 61(1):12‑50. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.cn112138‑20211027‑00751.

[6] Wang L, Peng W, Zhao Z, et al. Prevalence and treatment of diabetes in China, 2013—2018[J]. JAMA, 2021, 326(24):2498‑2506. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2021.22208.

[7] Sinclair A, Saeedi P, Kaundal A, et al. Diabetes and global ageing among 65‑99‑year‑old adults: findings from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9(th) edition[J]. Diabetes Res Clin Pract, 2020, 162: 108078. DOI: 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108078.

[8] Li Y, Teng D, Shi X, et al. Prevalence of diabetes recorded in mainland China using 2018 diagnostic criteria from the American Diabetes Association: national cross sectional study[J]. BMJ, 2020, 369:m997. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.m997.

[9] Bragg F, Holmes MV, Iona A, et al. Association between diabetes and cause‑specific mortality in rural and urban areas of China[J]. JAMA, 2017, 317(3): 280‑289. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2016.19720.

[10] Barnett KN, McMurdo ME, Ogston SA, et al. Mortality in people diagnosed with type 2 diabetes at an older age: a systematic review[J]. Age Ageing, 2006, 35(5): 463‑468. DOI: 10.1093/ageing/afl019.

[11] Ji L, Hu D, Pan C, et al. Primacy of the 3B approach to control risk factors for cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes patients[J]. Am J Med, 2013, 126(10): 925. e11‑e22. DOI: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.02.035.

[12] World Health Organization. Use of glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) in the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus: abbreviated report of a WHO consultation[M]. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2011.

[13] Picón MJ, Murri M, Muñoz A, et al. Hemoglobin A1c versus oral glucose tolerance test in postpartum diabetes screening[J]. Diabetes Care, 2012, 35(8):1648‑1653. DOI: 10.2337/dc11‑2111.

[14] Huang SH, Huang PJ, Li JY, et al. Hemoglobin A1c levels associated with age and gender in Taiwanese adults without prior diagnosis with diabetes[J]. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2021, 18(7): 3390. DOI: 10.3390/

[15] Lin L, Wang A, He Y, et al. Effects of the hemoglobin glycation index on hyperglycemia diagnosis: results from the REACTION study[J]. Diabetes Res Clin Pract, 2021, 180:109039. DOI: 10.1016/j.diabres.2021.109039.

[16] Kotwal A, Haddox C, Block M, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors: an emerging cause of insulin‑dependent diabetes[J]. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care, 2019, 7(1): e000591. DOI: 10.1136/bmjdrc‑2018‑000591.

[17] Aggarwal G, Kamada P, Chari ST. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus in pancreatic cancer compared to common cancers[J]. Pancreas, 2013, 42(2):198‑201. DOI: 10.1097/ MPA.0b013e3182592c96.

[18] Andersen DK, Korc M, Petersen GM, et al. Diabetes, pancreatogenic diabetes, and pancreatic cancer[J]. Diabetes, 2017, 66(5): 1103‑1110. DOI: 10.2337/ db16‑1477.

[19] Crandall JP, Mather K, Rajpathak SN, et al. Statin use and risk of developing diabetes: results from the Diabetes Prevention Program[J]. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care, 2017, 5(1):e000438. DOI: 10.1136/bmjdrc‑2017‑000438.

[20] 胡秀英, 龙纳, 吴琳娜, 等 . 中国老年人健康综合功能评价量表的研制 [J]. 四川大学学报 ( 医学版), 2013, 44(4): 610‑613.

[21] 樊瑾, 于普林, 李小鹰 . 中国健康老年人标准(2013)解读2——健康评估方法[J]. 中华老年医学杂志, 2014, 33(1): 1‑3. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254‑9026.2014.01.001.

[22] 茅范贞, 陈俊泽, 苏彩秀, 等 . 老年健康功能多维评定量表的研制[J].中国卫生统计, 2015, 32(3):379‑382.

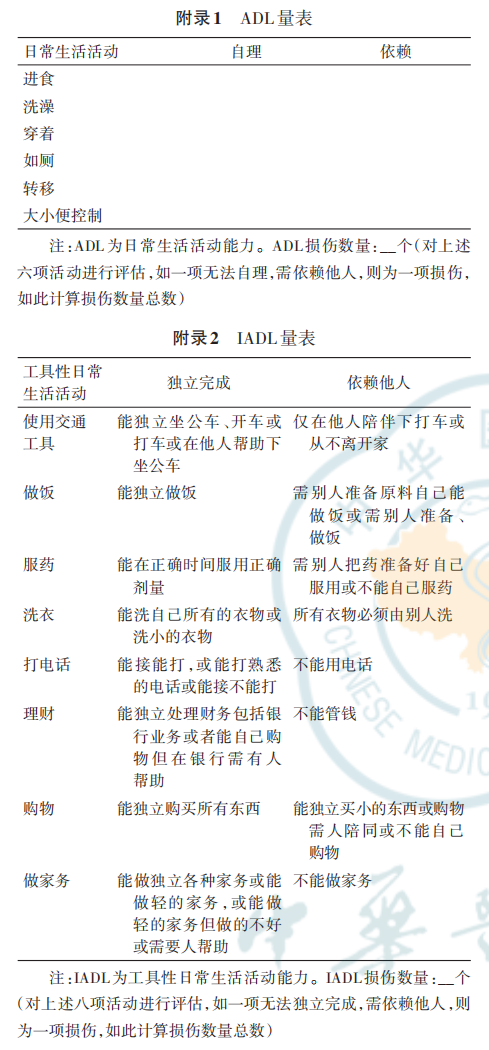

[23] Katz SC, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, et al. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of Adl: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function[J]. JAMA, 1963, 185(12): 914‑919. DOI: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016.

[24] Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self‑maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living [J]. Gerontologist, 1969, 9(3):179‑186.

[25] Liu Y, Xiao X, Peng C, et al. Development and implementation of couple‑based collaborative management model of type 2 diabetes mellitus for community‑dwelling Chinese older adults: a pilot randomized trial[J]. Front Public Health, 2021, 9:686282. DOI: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.686282.

[26] Li F, Guo S, Gong W, et al. Self‑management of diabetes for empty nest older adults: a randomized controlled trial[J]. West J Nurs Res, 2023, 45(10): 921‑931. DOI: 10.1177/01939459231191599.

[27] Sng GGR, Tung JYM, Lim DYZ, et al. Potential and pitfalls of ChatGPT and natural‑language artificial intelligence models for diabetes education[J]. Diabetes Care, 2023, 46(5):e103‑e105. DOI: 10.2337/dc23‑0197.

[28] Battelino T, Danne T, Bergenstal RM, et al. Clinical targets for continuous glucose monitoring data interpretation: recommendations from the international consensus on time in range[J]. 2019, 42(8):1593‑1603.

[29] American Diabetes Association. (6) Glycemic targets[J]. Diabetes Care, 2015, 38 Suppl: S33‑S40. DOI: 10.2337/ dc15‑S009.

[30] Rahi B, Morais JA, Gaudreau P, et al. Energy and protein intakes and their association with a decline in functional capacity among diabetic older adults from the NuAge cohort[J]. Eur J Nutr, 2016, 55(4): 1729‑1739. DOI: 10.1007/s00394‑015‑0991‑1.

[31] Op den Kamp CM, Langen RC, Haegens A, et al. Muscle atrophy in cachexia: can dietary protein tip the balance? [J]. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care, 2009, 12(6):611‑616. DOI: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e3283319399.

[32] Markova M, Pivovarova O, Hornemann S, et al. Isocaloric diets high in animal or plant protein reduce liver fat and inflammation in individuals with type 2 diabetes[J]. Gastroenterology, 2017, 152(3): 571‑585. e8. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.10.007.

[33] Shukla AP, Dickison M, Coughlin N, et al. The impact of food order on postprandial glycaemic excursions in prediabetes[J]. Diabetes Obes Metab, 2019, 21(2): 377‑381. DOI: 10.1111/dom.13503.

[34] Turnbull PJ, Sinclair AJ. Evaluation of nutritional status and its relationship with functional status in older citizens with diabetes mellitus using the mini nutritional assessment (MNA) tool‑‑a preliminary investigation[J]. J Nutr Health Aging, 2002, 6(3):185‑189.

[35] Tan S, Li W, Wang J. Effects of six months of combined aerobic and resistance training for elderly patients with a long history of type 2 diabetes[J]. J Sports Sci Med, 2012, 11(3):495‑501.

[36] Lu X, Zhao C. Exercise and type 1 diabetes[J]. Adv Exp Med Biol, 2020, 1228: 107‑121. DOI: 10.1007/978‑981‑15‑1792‑1_7.

[37] Sampath Kumar A, Maiya AG, Shastry BA, et al. Exercise and insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta‑analysis[J]. Ann Phys Rehabil Med, 2019, 62(2): 98‑103. DOI:

10.1016/j. rehab.2018.11.001.

[38] Dunstan DW, Daly RM, Owen N, et al. High‑intensity resistance training improves glycemic control in older patients with type 2 diabetes[J]. Diabetes Care, 2002, 25(10):1729‑1736. DOI: 10.2337/diacare.25.10.1729.

[39] Jansson AK, Chan LX, Lubans DR, et al. Effect of resistance training on HbA1c in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus and the moderating effect of changes in muscular strength: a systematic review and meta‑analysis[J]. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care, 2022, 10(2): e002595. DOI: 10.1136/bmjdrc‑2021‑002595.

[40] Morrison S, Colberg SR, Mariano M, et al. Balance training reduces falls risk in older individuals with type 2 diabetes [J]. Diabetes Care, 2010, 33(4): 748‑750. DOI: 10.2337/ dc09‑1699.

[41] Wang Y, Yan J, Zhang P, et al. Tai Chi Program to improve glucose control and quality of life for the elderly with type 2 diabetes: a Meta‑analysis[J]. Inquiry, 2022, 59: 469580211067934. DOI: 10.1177/00469580211067934.

[42] Chodzko‑Zajko WJ, Proctor DN, Fiatarone Singh MA, et al. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Exercise and physical activity for older adults[J]. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2009, 41(7): 1510‑1530. DOI: 10.1249/ MSS.0b013e3181a0c95c.

[43] Kanaley JA, Colberg SR, Corcoran MH, et al. Exercise/physical activity in individuals with type 2 diabetes: a consensus statement from the American College of Sports Medicine[J]. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2022, 54(2):353‑368. DOI: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000002800.

[44] Blonde L, Dailey GE, Jabbour SA, et al. Gastrointestinal tolerability of extended‑release metformin tablets compared to immediate‑release metformin tablets: results of a retrospective cohort study[J]. Curr Med Res Opin, 2004, 20(4):565‑572. DOI: 10.1185/030079904125003278.

[45] 二甲双胍临床应用专家共识 (2018 年 版)[J]. 中国糖尿病杂志 , 2019, 27(3): 161‑173. DOI: 10.3969/j. issn.1006‑6187.2019.03.001.

[46] Wong CW, Leung CS, Leung CP, et al. Association of metformin use with vitamin B(12) deficiency in the institutionalized elderly[J]. Arch Gerontol Geriatr, 2018, 79:57‑62. DOI: 10.1016/j.archger.2018.07.019.

[47] American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 13. Older adults: standards of care in diabetes —2024[J]. Diabetes Care, 2024, 47(Suppl 1): S244‑S257. DOI: 10.2337/dc24‑S013.

[48] 叶林虎, 贺梅, 赵欣黔, 等. 磺脲类降糖药的潜在药物相互作用研究进展[J].中国医院药学杂志, 2018, 38(12):1333‑1337. DOI: 10.13286/j.cnki.chinhosppharmacyj.2018.12.21.

[49] 中华医学会糖尿病学分会 . 中国 2 型糖尿病防治指南 (2020 年版) [J]. 中华糖尿病杂志, 2021, 13(4):315‑409. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.cn115791‑20210221‑00095.

[50] Zhang J, Guo L. Effectiveness of acarbose in treating elderly patients with diabetes with postprandial hypotension[J]. J Investig Med, 2017, 65(4):772‑783. DOI: 10.1136/jim‑2016‑000295.

[51] Dormandy JA, Charbonnel B, Eckland DJ, et al. Secondary prevention of macrovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes in the PROactive Study (PROspective pioglitAzone Clinical Trial In macroVascular Events): a randomised controlled trial[J]. Lancet, 2005, 366(9493): 1279‑1289. DOI: 10.1016/S0140‑6736(05)67528‑9.

[52] Lee M, Saver JL, Liao HW, et al. Pioglitazone for secondary stroke prevention: a systematic review and Meta‑analysis [J]. Stroke, 2017, 48(2): 388‑393. DOI: 10.1161/ STROKEAHA.116.013977.

[53] Yen CL, Wu CY, Tsai CY, et al. Pioglitazone reduces cardiovascular events and dementia but increases bone fracture in elderly patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a national cohort study[J]. Aging (Albany NY), 2023, 15(7):2721‑2733. DOI: 10.18632/aging.204643.

[54] Phatak HM, Yin DD. Factors associated with the effect‑size of thiazolidinedione (TZD) therapy on HbA(1c): a meta‑analysis of published randomized clinical trials[J]. Curr Med Res Opin, 2006, 22(11): 2267‑2278. DOI: 10.1185/030079906X148328.

[55] Schwartz AV, Chen H, Ambrosius WT, et al. Effects of TZD use and discontinuation on fracture rates in ACCORD bone study[J]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2015, 100(11): 4059‑4066. DOI: 10.1210/jc.2015‑1215.

[56] Billington EO, Grey A, Bolland MJ. The effect of thiazolidinediones on bone mineral density and bone turnover: systematic review and meta‑analysis[J]. Diabetologia, 2015, 58(10): 2238‑2246. DOI: 10.1007/ s00125‑015‑3660‑2.

[57] Mulvihill EE, Drucker DJ. Pharmacology, physiology, and mechanisms of action of dipeptidyl peptidase‑4 inhibitors [J]. Endocr Rev, 2014, 35(6): 992‑1019. DOI: 10.1210/ er.2014‑1035.

[58] Scheen AJ. The safety of gliptins: updated data in 2018[J]. Expert Opin Drug Saf, 2018, 17(4): 387‑405. DOI:10.1080/14740338.2018.1444027.

[59] Stafford S, Elahi D, Meneilly GS. Effect of the dipeptidyl peptidase‑4 inhibitor sitagliptin in older adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus[J]. J Am Geriatr Soc, 2011, 59(6): 1148‑1149. DOI: 10.1111/j.1532‑5415.2011.03438.x.

[60] Ledesma G, Umpierrez GE, Morley JE, et al. Efficacy and safety of linagliptin to improve glucose control in older people with type 2 diabetes on stable insulin therapy: a randomized trial[J]. Diabetes Obes Metab, 2019, 21(11): 2465‑2473. DOI: 10.1111/dom.13829.

[61] Bethel MA, Engel SS, Green JB, et al. Assessing the safety of sitagliptin in older participants in the trial evaluating cardiovascular outcomes with sitagliptin (TECOS) [J]. Diabetes Care, 2017, 40(4): 494‑501. DOI: 10.2337/ dc16‑1135.

[62] Cooper ME, Rosenstock J, Kadowaki T, et al. Cardiovascular and kidney outcomes of linagliptin treatment in older people with type 2 diabetes and established cardiovascular disease and/or kidney disease: a prespecified subgroup analysis of the randomized, placebo‑controlled CARMELINA® trial[J]. Diabetes Obes Metab, 2020, 22(7): 1062‑1073. DOI: 10.1111/dom.13995.

[63] Leiter LA, Teoh H, Braunwald E, et al. Efficacy and safety of saxagliptin in older participants in the SAVOR‑TIMI 53 trial[J]. Diabetes Care, 2015, 38(6): 1145‑1153. DOI: 10.2337/dc14‑2868.

[64] Gallo LA, Wright EM, Vallon V. Probing SGLT2 as a therapeutic target for diabetes: basic physiology and consequences[J]. Diab Vasc Dis Res, 2015, 12(2): 78‑89. DOI: 10.1177/1479164114561992.

[65] Lunati ME, Cimino V, Gandolfi A, et al. SGLT2‑inhibitors are effective and safe in the elderly: the SOLD study[J]. Pharmacol Res, 2022, 183: 106396. DOI: 10.1016/j. phrs.2022.106396.

[66] Tahrani AA, Barnett AH, Bailey CJ. SGLT inhibitors in management of diabetes[J]. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol, 2013, 1(2): 140‑151. DOI: 10.1016/S2213‑8587(13) 70050‑0.

[67] Wiviott SD, Raz I, Bonaca MP, et al. Dapagliflozin and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes[J]. N Engl J Med, 2019, 380(4): 347‑357. DOI: 10.1056/

[68] Neal B, Perkovic V, Mahaffey KW, et al. Canagliflozin and cardiovascular and renal events in type 2 diabetes[J]. N Engl J Med, 2017, 377(7): 644‑657. DOI: 10.1056/

[69] Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, et al. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes [J]. N Engl J Med, 2015, 373(22): 2117‑2128. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504720.

[70] Cannon CP, Pratley R, Dagogo‑Jack S, et al. Cardiovascular outcomes with ertugliflozin in type 2 diabetes[J]. N Engl J Med, 2020, 383(15): 1425‑1435. DOI: 10.1056/

[71] Ji L, Ma J, Li H, et al. Dapagliflozin as monotherapy in drug‑naive Asian patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized, blinded, prospective phase Ⅲ study[J]. Clin Ther, 2014, 36(1): 84‑100. e9. DOI: 10.1016/j. clinthera.2013.11.002.

[72] Yabe D, Shiki K, Homma G, et al. Efficacy and safety of the sodium‑glucose co‑transporter‑2 inhibitor empagliflozin in elderly Japanese adults (≥65 years) with type 2 diabetes: a randomized, double‑blind, placebo‑controlled, 52‑week clinical trial (EMPA‑ELDERLY)[J]. Diabetes Obes Metab, 2023, 25(12): 3538‑3548. DOI: 10.1111/ dom.15249.

[73] Karagiannis T, Tsapas A, Athanasiadou E, et al. GLP‑1 receptor agonists and SGLT2 inhibitors for older people with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta‑analysis[J]. Diabetes Res Clin Pract, 2021, 174: 108737. DOI: 10.1016/j.diabres.2021.108737.

[74] Monteiro P, Bergenstal RM, Toural E, et al. Efficacy and safety of empagliflozin in older patients in the EMPA‑REG OUTCOME® trial[J]. Age Ageing, 2019, 48(6): 859‑866. DOI: 10.1093/ageing/afz096.

[75] Mahaffey KW, Neal B, Perkovic V, et al. Canagliflozin for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular events: results from the CANVAS program (Canagliflozin Cardiovascular Assessment Study) [J]. Circulation, 2018, 137(4): 323‑334. DOI: 10.1161/ CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032038.

[76] Cahn A, Mosenzon O, Wiviott SD, et al. Efficacy and safety of dapagliflozin in the elderly: analysis from the DECLARE‑TIMI 58 Study[J]. Diabetes Care, 2020, 43(2): 468‑475. DOI: 10.2337/dc19‑1476.

[77] Perkovic V, Jardine MJ, Neal B, et al. Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy[J]. N Engl J Med, 2019, 380(24): 2295‑2306. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1811744.

[78] Mosenzon O, Wiviott SD, Cahn A, et al. Effects of dapagliflozin on development and progression of kidney disease in patients with type 2 diabetes: an analysis from the DECLARE‑TIMI 58 randomised trial[J]. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol, 2019, 7(8):606‑617. DOI: 10.1016/ S2213‑8587(19)30180‑9.

[79] Wanner C, Inzucchi SE, Lachin JM, et al. Empagliflozin and progression of kidney disease in type 2 diabetes[J]. N Engl J Med, 2016, 375(4): 323‑334. DOI: 10.1056/

[80] The EMPA‑KIDNEY Collaborative Group, Herrington WG, Staplin N, et al. Empagliflozin in patients with chronic kidney disease[J]. N Engl J Med. 2023, 388(2): 117‑127. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2204233.

[81] Heerspink HJL, Stefánsson BV, Correa‑Rotter R, et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with chronic kidney disease[J]. N Engl J Med, 2020, 383(15): 1436‑1446. DOI: 10.1056/

[82] Heerspink HJL, Sjöström CD, Jongs N, et al. Effects of dapagliflozin on mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease: a pre‑specified analysis from the DAPA‑CKD randomized controlled trial[J]. Eur Heart J, 2021, 42(13): 1216‑1227. DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab094.

[83] Böhm M, Butler J, Filippatos G, et al. Empagliflozin improves outcomes in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction irrespective of age[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2022, 80(1): 1‑18. DOI: 10.1016/j. jacc.2022.04.040.

[84] Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, et al. Empagliflozin in heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction[J]. N Engl J Med, 2021, 385(16): 1451‑1461. DOI: 10.1056/

[85] Packer M, Anker SD, Butler J, et al. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes with empagliflozin in heart failure[J]. N Engl J Med, 2020, 383(15): 1413‑1424. DOI: 10.1056/

[86] McMurray JJV, Solomon SD, Inzucchi SE, et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction[J]. N Engl J Med, 2019, 381(21): 1995‑2008. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911303.

[87] Peikert A, Martinez FA, Vaduganathan M, et al. Efficacy and safety of dapagliflozin in heart failure with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction according to age: the DELIVER Trial[J]. Circ Heart Fail, 2022, 15(10):e010080. DOI: 10.1161/ CIRCHEARTFAILURE.122.010080.

[88] Solomon SD, McMurray J, Claggett B, et al. Dapagliflozin in heart failure with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction[J]. N Engl J Med, 2022, 387(12):1089‑1098. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2206286.

[89] Pratley RE, Cannon CP, Cherney DZI, et al. Cardiorenal outcomes, kidney function, and other safety outcomes with ertugliflozin in older adults with type 2 diabetes (VERTIS CV): secondary analyses from a randomised, double‑blind trial[J]. Lancet Healthy Longev, 2023, 4(4): e143‑e154. DOI: 10.1016/S2666‑7568(23)00032‑6.

[90] 孔德华, 李敬文, 周红 . 钠‑葡萄糖共转运蛋白 2 抑制剂对 2型糖尿病患者酮症酸中毒影响的Meta分析[J]. 中华糖尿病杂志 , 2023, 15(2): 144‑151. DOI: 10.3760/cma. j. cn115791‑20220409‑00148.

[91] Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Diabetes Work Group. KDIGO 2022 clinical practice guideline for diabetes management in chronic kidney disease[J]. Kidney Int, 2022, 102(5S): S1‑S127. DOI: 10.1016/j.kint.2022.06.008.

[92] Madsbad S. Review of head‑to‑head comparisons of glucagon‑like peptide‑1 receptor agonists[J]. Diabetes Obes Metab, 2016, 18(4): 317‑332. DOI: 10.1111/ dom.12596.

[93] Singh S, Wright EE Jr, Kwan AY, et al. Glucagon‑like peptide‑1 receptor agonists compared with basal insulins for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta‑analysis[J]. Diabetes Obes Metab, 2017, 19(2):228‑238. DOI: 10.1111/dom.12805.

[94] Htike ZZ, Zaccardi F, Papamargaritis D, et al. Efficacy and safety of glucagon‑like peptide‑1 receptor agonists in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and mixed‑treatment comparison analysis[J]. Diabetes Obes Metab, 2017, 19(4):524‑536. DOI: 10.1111/dom.12849.

[95] Hamano K, Nishiyama H, Matsui A, et al. Efficacy and safety analyses across 4 subgroups combining low and high age and body mass index groups in Japanese phase 3 studies of dulaglutide 0.75 mg after 26 weeks of treatment[J]. Endocr J, 2017, 64(4): 449‑456. DOI:

10.1507/endocrj.EJ16‑0428. [96] Raccah D, Miossec P, Esposito V, et al. Efficacy and safety of lixisenatide in elderly (≥65 years old) and very elderly (≥75 years old) patients with type 2 diabetes : an analysis from the GetGoal phase Ⅲ programme[J]. Diabetes Metab Res Rev, 2015, 31(2):204 ‑ 211. DOI: 10.1002/dmrr.2588.

[97] Bode BW, Brett J, Falahati A, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and tolerability profile of liraglutide, a once‑daily human GLP‑1 analog, in patients with type 2 diabetes≥65 and<65 years of age: a pooled analysis from phase Ⅲ studies[J]. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother, 2011, 9(6): 423‑433. DOI: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2011.09.007.

[98] Kristensen SL, Rørth R, Jhund PS, et al. Cardiovascular, mortality, and kidney outcomes with GLP‑1 receptor agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta‑analysis of cardiovascular outcome trials [J]. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol, 2019, 7(10): 776‑785.DOI: 10.1016/S2213‑8587(19)30249‑9.

[99] Gerstein HC, Colhoun HM, Dagenais GR, et al. Dulaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes (REWIND): a double‑blind, randomised placebo‑controlled trial[J]. Lancet, 2019, 394(10193):121‑130. DOI: 10.1016/S0140‑6736(19) 31149‑3.

[100] Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown‑Frandsen K, et al. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes[J]. N Engl J Med, 2016, 375(4): 311‑322. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603827.

[101] Marso SP, Bain SC, Consoli A, et al. Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes [J]. N Engl J Med, 2016, 375(19): 1834‑1844. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1607141.

[102] Pfeffer MA, Claggett B, Diaz R, et al. Lixisenatide in patients with type 2 diabetes and acute coronary syndrome[J]. N Engl J Med, 2015, 373(23): 2247‑2257. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1509225.

[103] Holman RR, Bethel MA, Mentz RJ, et al. Effects of once‑weekly exenatide on cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes[J]. N Engl J Med, 2017, 377(13): 1228‑1239. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1612917.

[104] Li C, Luo J, Jiang M, et al. The efficacy and safety of the combination therapy with GLP‑1 receptor agonists and SGLT‑2 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and Meta‑analysis[J]. Front Pharmacol, 2022, 13: 838277. DOI: 10.3389/fphar.2022.838277.

[105] Riley DR, Essa H, Austin P, et al. All‑cause mortality and cardiovascular outcomes with sodium‑glucose co‑transporter 2 inhibitors, glucagon‑like peptide‑1 receptor agonists and with combination therapy in people with type 2 diabetes[J]. Diabetes Obes Metab, 2023, 25(10):2897‑2909. DOI: 10.1111/dom.15185.

[106] Sinclair AJ, Dashora U, George S, et al. Joint British Diabetes Societies for Inpatient Care (JBDS‑IP) Clinical Guideline Inpatient care of the frail older adult with diabetes: an Executive Summary[J]. Diabet Med, 2020, 37(12):1981‑1991. DOI: 10.1111/dme.14341.

[107] Sodhi M, Rezaeianzadeh R, Kezouh A, et al. Risk of gastrointestinal adverse events associated with glucagon‑like peptide‑1 receptor agonists for weight loss [J]. JAMA, 2023, 330(18): 1795‑1797. DOI: 10.1001/ jama.2023.19574.

[108] 冉兴无,母义明,朱大龙,等.成人2型糖尿病基础胰岛素临床应用中国专家指导建议(2020版)[J]. 中国糖尿病杂志, 2020,28(10):721‑728. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1006‑6187.2020.10.001.

[109] Blonde L, Umpierrez GE, Reddy SS, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinology clinical practice guideline: developing a diabetes mellitus comprehensive care plan—2022 update[J]. Endocr Pract, 2022, 28(10): 923‑1049. DOI: 10.1016/j.eprac.2022.08.002.

[110] Philis‑Tsimikas A, Astamirova K, Gupta Y, et al. Similar glycaemic control with less nocturnal hypoglycaemia in a 38‑week trial comparing the IDegAsp co‑formulation with insulin glargine U100 and insulin aspart in basal insulin‑treated subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus[J]. Diabetes Res Clin Pract, 2019, 147: 157‑165. DOI: 10.1016/j.diabres.2018.10.024.

[111] Brunner M, Pieber T, Korsatko S, et al. The distinct prandial and basal pharmacodynamics of IDegAsp observed in younger adults are preserved in elderly subjects with type 1 diabetes[J]. Drugs Aging, 2015, 32(7): 583‑590. DOI: 10.1007/s40266‑015‑0272‑y.

[112] Fulcher G, Mehta R, Fita EG, et al. Efficacy and safety of IDegAsp versus BIAsp 30, both twice daily, in elderly patients with type 2 diabetes: post hoc analysis of two phase 3 randomized controlled BOOST trials[J]. Diabetes Ther,2019, 10(1): 107‑118. DOI: 10.1007/ s13300‑018‑0531‑0.

[113] Kaneko S, da Rocha Fernandes JD, Yamamoto Y, et al. A Japanese study assessing glycemic control with use of IDegAsp co‑formulation in patients with type 2 diabetes in clinical practice: the JAGUAR study[J]. Adv Ther, 2021, 38(3):1638‑1649. DOI: 10.1007/s12325‑021‑01623‑y.

[114] Wallia A, Molitch ME. Insulin therapy for type 2 diabetes mellitus[J]. JAMA, 2014, 311(22): 2315‑2325. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2014.5951.

[115] ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, et al. 9. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment: standards of care in diabetes—2023[J]. Diabetes Care, 2023, 46(Suppl 1): S140‑S157. DOI: 10.2337/dc23‑S009.

[116] Handelsman Y, Chovanes C, Dex T, et al. Efficacy and safety of insulin glargine/lixisenatide (iGlarLixi) fixed‑ratio combination in older adults with type 2 diabetes[J]. J Diabetes Complications, 2019, 33(3): 236‑242. DOI: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2018.11.009.

[117] Billings LK, Agner B, Altuntas Y, et al. The benefit of insulin degludec/liraglutide (IDegLira) compared with basal‑bolus insulin therapy is consistent across participant subgroups with type 2 diabetes in the DUAL Ⅶ randomized trial [J]. J Diabetes Sci Technol, 2021, 15(3): 636‑645. DOI: 10. 1177 /1932296820906888 .

[118] 《以二甲双胍为基础的固定复方制剂治疗2型糖尿病专家共识》编写组. 以二甲双胍为基础的固定复方制剂治疗2型糖尿病专家共识[J].中华糖尿病杂志, 2022, 14(12):1380‑1386.DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.cn115791‑20220930‑00505.

[119] Bajaj HS, Ye C, Jain E, et al. Glycemic improvement with a fixed‑dose combination of DPP‑4 inhibitor + metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes (GIFT study) [J]. Diabetes Obes Metab, 2018, 20(1): 195‑199. DOI: 10.1111/ dom.13040.

[120] Rosenstock J, Aronson R, Grunberger G, et al. Benefits of lixiLan, a titratable fixed‑ratio combination of insulin glargine plus lixisenatide, versus insulin glargine and lixisenatide mono components in type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled on oral agents: the LixiLan‑O randomized trial[J]. Diabetes Care, 2016, 39(11): 2026‑2035. DOI: 10.2337/dc16‑0917.

[121] Yuan X, Guo X, Zhang J, et al. Improved glycaemic control and weight benefit with iGlarLixi versus insulin glargine 100 U/mL in Chinese people with type 2 diabetes advancing their therapy from basal insulin plus oral antihyperglycaemic drugs: results from the LixiLan‑L‑CN randomized controlled trial[J]. Diabetes Obes Metab, 2022, 24(11):2182‑2191. DOI: 10.1111/dom.14803.

[122] Blonde L, Rosenstock J, Del Prato S, et al. Switching to iGlarLixi versus continuing daily or weekly GLP‑1 RA in type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled by GLP‑1RA and oral antihyperglycemic therapy: the LixiLan‑G randomized clinical trial[J]. Diabetes Care, 2019, 42(11): 2108‑2116. DOI: 10.2337/dc19‑1357.

[123] Wang W, Agner BFR, Luo B, et al. DUAL I China: improved glycemic control with IDegLira versus its individual components in a randomized trial with Chinese participants with type 2 diabetes uncontrolled on oral antidiabetic drugs[J]. J Diabetes, 2022, 14(6): 401‑413. DOI: 10.1111/1753‑0407.13286.

[124] Pei Y, Agner BR, Luo B, et al. DUAL Ⅱ China: superior HbA1c reductions and weight loss with insulin degludec/liraglutide (IDegLira) versus insulin degludec in a randomized trial of Chinese people with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled on basal insulin[J]. Diabetes Obes Metab, 2021, 23(12): 2687‑2696. DOI: 10.1111/dom.14522.

[125] Linjawi S, Bode BW, Chaykin LB, et al. The efficacy of IDegLira (insulin degludec/liraglutide combination) in adults with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with a GLP‑1 receptor agonist and oral therapy: DUAL Ⅲ randomized clinical trial[J]. Diabetes Ther, 2017, 8(1): 101‑114. DOI: 10.1007/s13300‑016‑0218‑3.

[126] Komatsu M, Watada H, Kaneko S, et al. Efficacy and safety of the fixed‑ratio combination of insulin degludec and liraglutide by baseline glycated hemoglobin, body mass index and age in Japanese individuals with type 2 diabetes: a subgroup analysis of two phase Ⅲ trials [J]. Diabetes Investig, 2021, 12(9):1610‑1618. DOI: J 1111 / jdi.13525.

[127] Zhang XH, Tian YF, Huang GL, et al. Advances in studies of Chiglitazar Sodium, a novel PPAR pan‑agonist, for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus[J]. Curr Med Sci, 2023, 43(5):890‑896. DOI: 10.1007/s11596‑023‑2760‑3.

[128] Toulis KA, Nirantharakumar K, Pourzitaki C, et al. Glucokinase activators for type 2 diabetes: challenges and future developments[J]. Drugs, 2020, 80(5):467‑475. DOI: 10.1007/s40265‑020‑01278‑z.

[129] Einarson TR, Acs A, Ludwig C, et al. Prevalence of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes: a systematic literature review of scientific evidence from across the world in 2007—2017[J]. Cardiovasc Diabetol, 2018, 17(1):83. DOI: 10.1186/s12933‑018‑0728‑6.

[130] Sarwar N, Gao P, Seshasai SR, et al. Diabetes mellitus, fasting blood glucose concentration, and risk of vascular disease: a collaborative meta‑analysis of 102 prospective studies[J]. Lancet, 2010, 375(9733): 2215‑2222. DOI: 10.1016/S0140‑6736(10)60484‑9.

[131] Lacey B, Lewington S, Clarke R, et al. Age‑specific association between blood pressure and vascular and non‑vascular chronic diseases in 0.5 million adults in China: a prospective cohort study[J]. Lancet Glob Health, 2018, 6(6): e641‑e649. DOI: 10.1016/S2214‑109X(18) 30217‑1.

[132] Brunström M, Carlberg B. Effect of antihypertensive treatment at different blood pressure levels in patients with diabetes mellitus: systematic review and meta‑analyses[J]. BMJ, 2016, 352:i717. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.

[133] Beckett NS, Peters R, Fletcher AE, et al. Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older[J]. N Engl J Med, 2008, 358(18): 1887‑1898. DOI: 10.1056/

[134] Cushman WC, Evans GW, Byington RP, et al. Effects of intensive blood‑pressure control in type 2 diabetes mellitus[J]. N Engl J Med, 2010, 362(17):1575‑1585. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001286.

[135] Zhang W, Zhang S, Deng Y, et al. Trial of intensive blood‑pressure control in older patients with hypertension[J]. N Engl J Med, 2021, 385(14):1268‑1279. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2111437.

[136] ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, et al. 13. Older adults: standards of care in diabetes—2023[J]. Diabetes Care, 2023, 46(Suppl 1):S216‑S229. DOI: 10.2337/dc23‑S013.

[137] Weiss J, Freeman M, Low A, et al. Benefits and harms of intensive blood pressure treatment in adults aged 60 years or older: a systematic review and Meta‑analysis[J]. Ann Intern Med, 2017, 166(6): 419‑429. DOI: 10.7326/ M16‑1754.

[138] Cheng J, Zhang W, Zhang X, et al. Effect of angiotensin‑converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin Ⅱ receptor blockers on all‑cause mortality, cardiovascular deaths, and cardiovascular events in patients with diabetes mellitus: a meta‑analysis[J]. JAMA Intern Med, 2014, 174(5): 773‑785. DOI: 10.1001/ jamainternmed.2014.348.

[139] Lindholm LH, Hansson L, Ekbom T, et al. Comparison of antihypertensive treatments in preventing cardiovascular events in elderly diabetic patients: results from the Swedish Trial in Old Patients with Hypertension‑2. STOP Hypertension‑2 Study Group[J]. J Hypertens, 2000, 18(11): 1671‑1675. DOI: 10.1097/00004872‑200018110‑00020.

[140] Catalá‑López F, Macías Saint‑Gerons D, González‑Bermejo D, et al. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes of renin‑angiotensin system blockade in adult patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review with network Meta‑analyses[J]. PLoS Med, 2016, 13(3):e1001971. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001971.

[141] Elgendy IY, Huo T, Chik V, et al. Efficacy and safety of angiotensin receptor blockers in older patients: a meta‑analysis of randomized trials[J]. Am J Hypertens, 2015, 28(5):576‑585. DOI: 10.1093/ajh/hpu209.

[142] 血脂异常老年人使用他汀类药物中国专家共识组. 血脂异 常老年人使用他汀类药物中国专家共识[J].中华内科杂志, 2015, 54(5): 467‑477. DOI: 10.3760/cma. issn.0578‑1426.2015.05.020.

[143] 海峡两岸医药卫生交流协会老年医学专业委员会≥75岁老年患者血脂异常管理的专家共识[J].中国心血管杂志,2020, 25(3):201‑209. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1007‑5410.2020.03.001.

[144] Cholesterol Treatment Trialists′ Collaboration. Efficacy and safety of statin therapy in older people: a meta‑analysis of individual participant data from 28 randomised controlled trials[J]. Lancet, 2019, 393(10170): 407‑415. DOI: 10.1016/S0140‑6736(18) 31942‑1.

[145] Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group. The effects of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin on cause‑specific mortality and on cancer incidence in 20, 536 high‑risk people: a randomised placebo‑controlled trial [ISRCTN48489393][J]. BMC Med, 2005, 3:6. DOI: 10.1186/1741‑7015‑3‑6.

[146] Olafsdottir E, Aspelund T, Sigurdsson G, et al. Effects of statin medication on mortality risk associated with type 2 diabetes in older persons: the population‑based AGES‑Reykjavik Study[J]. BMJ Open, 2011, 1(1):e000132. DOI: 10.1136/bmjopen‑2011‑000132.

[147] Collins R, Armitage J, Parish S, et al. MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol‑lowering with simvastatin in 5963 people with diabetes: a randomised placebo‑controlled trial[J]. Lancet, 2003, 361(9374): 2005‑2016. DOI: 10.1016/s0140‑6736(03)13636‑7.

[148] Neil HA, DeMicco DA, Luo D, et al. Analysis of efficacy and safety in patients aged 65‑75 years at randomization: collaborative atorvastatin diabetes study (CARDS) [J]. Diabetes Care, 2006, 29(11): 2378‑2384. DOI: 10.2337/ dc06‑0872.

[149] Bohula EA, Wiviott SD, Giugliano RP, et al. Prevention of stroke with the addition of ezetimibe to statin therapy in patients with acute coronary syndrome in IMPROVE‑IT (improved reduction of outcomes: Vytorin efficacy international trial)[J]. Circulation, 2017, 136(25):2440‑2450. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.029095.

[150] Giugliano RP, Cannon CP, Blazing MA, et al. Benefit of adding ezetimibe to statin therapy on cardiovascular outcomes and safety in patients with versus without diabetes mellitus: results from IMPROVE‑IT (improved reduction of outcomes: Vytorin efficacy international trial) [J]. Circulation, 2018, 137(15): 1571‑1582. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030950.

[151] McNeil JJ, Nelson MR, Woods RL, et al. Effect of aspirin on all‑cause mortality in the healthy elderly[J]. N Engl J Med, 2018, 379(16):1519‑1528. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1803955.

[152] Wang M, Yu H, Li Z, et al. Benefits and risks associated with low‑dose aspirin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and Meta‑analysis of randomized control trials and trial sequential analysis[J]. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs, 2022, 22(6):657‑675. DOI: 10.1007/s40256‑022‑00537‑6.

[153] Gu D, Kelly TN, Wu X, et al. Mortality attributable to smoking in China[J]. N Engl J Med, 2009, 360(2):150‑159. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMsa0802902.

[154] Chen Z, Peto R, Zhou M, et al. Contrasting male and female trends in tobacco‑attributed mortality in China: evidence from successive nationwide prospective cohort studies[J]. Lancet, 2015, 386(10002): 1447‑1456. DOI: 10.1016/ S0140‑6736(15)00340‑2.

[155] He Y, Lam TH, Jiang B, et al. Passive smoking and risk of peripheral arterial disease and ischemic stroke in Chinese women who never smoked[J]. Circulation, 2008, 118(15): 1535‑1540. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.784801.

[156] He Y, Lam TH, Jiang B, et al. Combined effects of tobacco smoke exposure and metabolic syndrome on cardiovascular risk in older residents of China[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2009, 53(4): 363‑371. DOI: 10.1016/j. jacc.2008.08.073.

[157] Mons U, Müezzinler A, Gellert C, et al. Impact of smoking and smoking cessation on cardiovascular events and mortality among older adults: meta‑analysis of individual participant data from prospective cohort studies of the CHANCES consortium[J]. BMJ, 2015, 350: h1551. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.h1551.

[158] Villareal DT, Chode S, Parimi N, et al. Weight loss, exercise, or both and physical function in obese older adults[J]. N Engl J Med, 2011, 364(13): 1218‑1229. DOI: 10.1056/

[159] Zhang L, Long J, Jiang W, et al. Trends in chronic kidney disease in China[J]. N Engl J Med, 2016, 375(9):905‑906. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMc1602469.

[160] Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Diabetes Work Group. KDIGO 2020 clinical practice guideline for diabetes management in chronic kidney disease[J]. Kidney Int, 2020, 98(4S): S1‑S115. DOI: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.06.019.

[161] American Diabetes Association. 11. Microvascular complications and foot care: standards of medical care in diabetes—2020[J]. Diabetes Care, 2020, 43(Suppl 1): S135‑S151. DOI: 10.2337/dc20‑S011.

[162] Yan ST, Liu JY, Tian H, et al. Clinical and pathological analysis of renal damage in elderly patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus[J]. Clin Exp Med, 2016, 16(3):437‑442. DOI: 10.1007/s10238‑015‑0362‑5.

[163] Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate[J]. Ann Intern Med, 2009, 150(9):604‑612. DOI: 10.7326/0003‑4819‑150‑9‑200905050‑00006.

[164] Guo M, Niu JY, Ye XW, et al. Evaluation of various equations for estimating renal function in elderly Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus[J]. Clin Interv Aging, 2017, 12:1661‑1672. DOI: 10.2147/CIA.S140289.

[165] Mills KT, Chen J, Yang W, et al. Sodium excretion and the risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with chronic kidney disease[J]. JAMA, 2016, 315(20): 2200‑2210. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2016.4447.

[166] Bakris GL, Agarwal R, Anker SD, et al. Effect of finerenone on chronic kidney disease outcomes in type 2 diabetes[J]. N Engl J Med, 2020, 383(23): 2219‑2229. DOI: 10.1056/

[167] Zhang H, Xie J, Hao C, et al. Finerenone in patients with chronic kidney disease and type 2 diabetes: the FIDELIO‑DKD subgroup from China[J]. Kidney Dis (Basel), 2023, 9(6):498‑506. DOI: 10.1159/000531997.

[168] Pitt B, Filippatos G, Agarwal R, et al. Cardiovascular events with Finerenone in kidney disease and type 2 diabetes[J]. N Engl J Med, 2021, 385(24):2252‑2263. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2110956.

[169] Bakris GL, Ruilope LM, Anker SD, et al. A prespecified exploratory analysis from FIDELITY examined finerenone use and kidney outcomes in patients with chronic kidney disease and type 2 diabetes[J]. Kidney Int, 2023, 103(1): 196‑206. DOI: 10.1016/j.kint.2022.08.040.

[170] 中华医学会糖尿病学分会视网膜病变学组. 糖尿病视网膜病变防治专家共识[J]. 中华糖尿病杂志 , 2018, 10(4): 241‑247. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1674‑5809.2018.04.001.

[171] Kapoor I, Sarvepalli SM, D′Alessio D, et al. GLP‑1 receptor agonists and diabetic retinopathy: a meta‑analysis of randomized clinical trials[J]. Surv Ophthalmol, 2023, 68(6): 1071‑1083. DOI: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2023.07.002.

[172] Bethel MA, Diaz R, Castellana N, et al. HbA(1c) change and diabetic retinopathy during GLP‑1 receptor agonist cardiovascular outcome trials: a Meta‑analysis and Meta‑regression[J]. Diabetes Care, 2021, 44(1): 290‑296. DOI: 10.2337/dc20‑1815.

[173] Schmidt‑Erfurth U, Garcia‑Arumi J, Bandello F, et al. Guidelines for the management of diabetic macular edema by the European Society of Retina Specialists (EURETINA) [J]. Ophthalmologica, 2017, 237(4):185‑222. DOI: 10.1159/000458539.

[174] Drinkwater JJ, Davis WA, Davis T. A systematic review of risk factors for cataract in type 2 diabetes[J]. Diabetes Metab Res Rev, 2019, 35(1): e3073. DOI: 10.1002/ dmrr.3073.

[175] GBD 2019 Blindness and Vision Impairment Collaborators, Vision Loss Expert Group of the Global Burden of Disease Study. Causes of blindness and vision impairment in 2020 and trends over 30 years, and prevalence of avoidable blindness in relation to VISION 2020: the right to sight: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study[J]. Lancet Glob Health, 2021, 9(2): e144‑e160. DOI: 10.1016/S2214‑109X(20)30489‑7.

[176] Song BJ, Aiello LP, Pasquale LR. Presence and risk factors for glaucoma in patients with diabetes[J]. Curr Diab Rep, 2016, 16(12):124. DOI: 10.1007/s11892‑016‑0815‑6.

[177] Song P, Xia W, Wang M, et al. Variations of dry eye disease prevalence by age, sex and geographic characteristics in China: a systematic review and meta‑analysis[J]. J Glob Health, 2018, 8(2):020503. DOI: 10.7189/jogh.08.020503.

[178] Yoo TK, Oh E. Diabetes mellitus is associated with dry eye syndrome: a meta‑analysis[J]. Int Ophthalmol, 2019, 39(11):2611‑2620. DOI: 10.1007/s10792‑019‑01110‑y.

[179] Zou X, Lu L, Xu Y, et al. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of dry eye disease in community‑based type 2 diabetic patients: the Beixinjing eye study[J]. BMC Ophthalmol, 2018, 18(1): 117. DOI: 10.1186/ s12886‑018‑0781‑7.

[180] The definition and classification of dry eye disease: report of the Definition and Classification Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye WorkShop (2007) [J]. Ocul Surf, 2007, 5(2): 75‑92. DOI: 10.1016/s1542‑0124(12) 70081‑2.

[181] Wu M, Liu X, Han J, et al. Association between sleep quality, mood status, and ocular surface characteristics in patients with dry eye disease[J]. Cornea, 2019, 38(3): 311‑317. DOI: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001854.

[182] Pop‑Busui R, Evans GW, Gerstein HC, et al. Effects of cardiac autonomic dysfunction on mortality risk in the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) trial[J]. Diabetes Care, 2010, 33(7):1578‑1584. DOI: 10.2337/dc10‑0125.

[183] Pop‑Busui R, Boulton AJ, Feldman EL, et al. Diabetic neuropathy: a position statement by the American Diabetes Association[J]. Diabetes Care, 2017, 40(1): 136‑154. DOI: 10.2337/dc16‑2042.

[184] Mao F, Zhu X, Liu S, et al. Age as an independent risk factor for diabetic peripheral neuropathy in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes[J]. Aging Dis, 2019, 10(3): 592‑600. DOI: 10.14336/AD.2018.0618.

[185] 潘琦, 王晓霞, 王忆力, 等. 北京地区老年糖尿病患者周围神经病变现况调查[J].中华老年医学杂志, 2018, 37(9):1036‑1041. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254‑9026.2018.09.020.

[186] Pan Q, Li Q, Deng W, et al. Prevalence and diagnosis of diabetic cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy in Beijing, China: a retrospective multicenter clinical study[J]. Front Neurosci, 2019, 13:1144. DOI: 10.3389/fnins.2019.01144.

[187] 张丽娜, 潘琦, 黄薇, 等. 北京地区2型糖尿病患者糖尿病心脏自主神经病变现况调查[J].中华糖尿病杂志, 2021, 13(6): 570‑577. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.cn115791‑20201217‑00717.

[188] Nyiraty S, Pesei F, Orosz A, et al. Cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy and glucose variability in patients with type 1 diabetes: is there an association? [J]. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 2018, 9: 174. DOI: 10.3389/ fendo.2018.00174.

[189] Su X, He J, Cui J, et al. The effects of aerobic exercise combined with resistance training on inflammatory factors and heart rate variability in middle‑aged and elderly women with type 2 diabetes mellitus[J]. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol, 2022, 27(6): e12996. DOI: 10.1111/anec.12996.

[190] Arnold AC, Raj SR. Orthostatic hypotension: a practical approach to investigation and management[J]. Can J Cardiol, 2017, 33(12): 1725‑1728. DOI: 10.1016/j. cjca.2017.05.007.

[191] Price R, Smith D, Franklin G, et al. Oral and topical treatment of painful diabetic polyneuropathy: practice guideline update summary: report of the AAN Guideline Subcommittee[J]. Neurology, 2022, 98(1): 31‑43. DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000013038.

[192] Tesfaye S, Sloan G, Petrie J, et al. Comparison of amitriptyline supplemented with pregabalin, pregabalin supplemented with amitriptyline, and duloxetine supplemented with pregabalin for the treatment of diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain (OPTION‑DM): a multicentre, double‑blind, randomised crossover trial[J]. Lancet, 2022, 400(10353): 680‑690. DOI: 10.1016/ S0140‑6736(22)01472‑6.

[193] Zhang X, Ran X, Xu Z, et al. Epidemiological characteristics of lower extremity arterial disease in Chinese diabetes patients at high risk: a prospective, multicenter, cross‑sectional study[J]. J Diabetes Complications, 2018, 32(2):150‑156. DOI: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2017.10.003.

[194] Gao Q, He B, Zhu C, et al. Factors associated with lower extremity atherosclerotic disease in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a case‑control study[J]. Medicine (Baltimore), 2016, 95(51):e5230. DOI: 10.1097/ MD.0000000000005230.

[195] Criqui MH, Langer RD, Fronek A, et al. Mortality over a period of 10 years in patients with peripheral arterial disease[J]. N Engl J Med, 1992, 326(6): 381‑386. DOI: 10.1056/NEJM199202063260605.

[196] 林少达, 林楚佳, 王爱红, 等 . 中国部分省市糖尿病足调查及神经病变分析 [J]. 中华医学杂志 , 2007, 87(18): 1241‑1244. DOI: 10.3760/j:issn:0376‑2491.2007.18.006.

[197] 许景灿, 王娅平, 陈燕, 等 . 基于多中心的中国糖尿病足患者临床资料分析[J]. 中南大学学报(医学版), 2019, 44(8):898‑904. DOI: 10.11817/j.issn.1672‑7347.2019.180746.

[198] Ren M, Yang C, Lin DZ, et al. Effect of intensive nursing education on the prevention of diabetic foot ulceration among patients with high‑risk diabetic foot: a follow‑up analysis[J]. Diabetes Technol Ther, 2014, 16(9): 576‑581. DOI: 10.1089/dia.2014.0004.

[199] Hinchliffe RJ, Brownrigg JR, Apelqvist J, et al. IWGDF guidance on the diagnosis, prognosis and management of peripheral artery disease in patients with foot ulcers in diabetes[J]. Diabetes Metab Res Rev, 2016, 32 Suppl 1: 37‑44. DOI: 10.1002/dmrr.2698.

[200] Almdal T, Nielsen AA, Nielsen KE, et al. Increased healing in diabetic toe ulcers in a multidisciplinary foot clinic: an observational cohort study[J]. Diabetes Res Clin Pract, 2015, 110(3):315‑321. DOI: 10.1016/j.diabres.2015.10.003.

[201] Whitmer RA, Karter AJ, Yaffe K, et al. Hypoglycemic episodes and risk of dementia in older patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus[J]. JAMA, 2009, 301(15): 1565‑1572. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2009.460.

[202] ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, et al. 1. Improving care and promoting health in populations: standards of care in diabetes—2023[J]. Diabetes Care, 2023, 46(Supple 1): S10‑S18. DOI: 10.2337/dc23‑S001.

[203] Yun JS, Ko SH. Risk factors and adverse outcomes of severe hypoglycemia in type 2 diabetes mellitus[J]. Diabetes Metab J, 2016, 40(6): 423‑432. DOI: 10.4093/ dmj.2016.40.6.423.

[204] Piątkiewicz P, Buraczewska‑Leszczyńska B, Kuczerowski R, et al. Severe hypoglycaemia in elderly patients with type 2 diabetes and coexistence of cardiovascular history [J]. Kardiol Pol, 2016, 74(8): 779‑785. DOI: 10.5603/KP. a2016.0043.

[205] Freeman J. Management of hypoglycemia in older adults with type 2 diabetes[J]. Postgrad Med, 2019, 131(4): 241‑250. DOI: 10.1080/00325481.2019.1578590.

[206] Punthakee Z, Miller ME, Launer LJ, et al. Poor cognitive function and risk of severe hypoglycemia in type 2 diabetes: post hoc epidemiologic analysis of the ACCORD trial[J]. Diabetes Care, 2012, 35(4): 787‑793. DOI: 10.2337/dc11‑1855.

[207] Hope SV, Taylor PJ, Shields BM, et al. Are we missing hypoglycaemia? Elderly patients with insulin‑treated diabetes present to primary care frequently with non‑specific symptoms associated with hypoglycaemia[J]. Prim Care Diabetes, 2018, 12(2):139‑146. DOI: 10.1016/j. pcd.2017.08.004.

[208] Stahn A, Pistrosch F, Ganz X, et al. Relationship between hypoglycemic episodes and ventricular arrhythmias in patients with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular diseases: silent hypoglycemias and silent arrhythmias[J]. Diabetes Care, 2014, 37(2): 516‑520. DOI: 10.2337/ dc13‑0600.

[209] Heller SR, Cryer PE. Reduced neuroendocrine and symptomatic responses to subsequent hypoglycemia after 1 episode of hypoglycemia in nondiabetic humans [J]. Diabetes, 1991, 40(2): 223‑226. DOI: 10.2337/ diab.40.2.223.

[210] Seaquist ER, Anderson J, Childs B, et al. Hypoglycemia and diabetes: a report of a workgroup of the American Diabetes Association and the Endocrine Society[J]. Diabetes Care, 2013, 36(5): 1384‑1395. DOI: 10.2337/ dc12‑2480.

[211] UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Intensive blood‑glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33)[J]. Lancet, 1998, 352(9131):837‑853.

[212] Polonsky WH, Peters AL, Hessler D. The impact of real‑time continuous glucose monitoring in patients 65 years and older[J]. J Diabetes Sci Technol, 2016, 10(4): 892‑897. DOI: 10.1177/1932296816643542.

[213] 中华医学会糖尿病学分会 . 中国 2 型糖尿病防治指南 (2017 年版)[J]. 中华糖尿病杂志, 2018, 10(1):4‑67. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1674‑5809.2018.01.003.

[214] Abdelhafiz AH, Rodríguez‑Mañas L, Morley JE, et al. Hypoglycemia in older people——a less well recognized risk factor for frailty[J]. Aging Dis, 2015, 6(2): 156‑167. DOI: 10.14336/AD.2014.0330.

[215] Bonds DE, Kurashige EM, Bergenstal R, et al. Severe hypoglycemia monitoring and risk management procedures in the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) trial[J]. Am J Cardiol, 2007, 99(12A):80i‑89i. DOI: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.03.026.

[216] Lipska KJ, Krumholz H, Soones T, et al. Polypharmacy in the aging patient: a review of glycemic control in older adults with type 2 diabetes[J]. JAMA, 2016, 315(10): 1034‑1045. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2016.0299.

[217] Weinstock RS, Xing D, Maahs DM, et al. Severe hypoglycemia and diabetic ketoacidosis in adults with type 1 diabetes: results from the T1D Exchange clinic registry[J]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2013, 98(8): 3411‑3419. DOI: 10.1210/jc.2013‑1589.

[218] Pratley RE, Kanapka LG, Rickels MR, et al. Effect of continuous glucose monitoring on hypoglycemia in older adults with type 1 diabetes: a randomized clinical trial[J]. JAMA, 2020, 323(23): 2397‑2406. DOI: 10.1001/ jama.2020.6928.

[219] Kitabchi AE, Umpierrez GE, Miles JM, et al. Hyperglycemic crises in adult patients with diabetes[J]. Diabetes Care, 2009, 32(7):1335‑1343. DOI: 10.2337/dc09‑9032.

[220] Kitabchi AE, Umpierrez GE, Murphy MB, et al. Management of hyperglycemic crises in patients with diabetes[J]. Diabetes Care, 2001, 24(1): 131‑153. DOI: 10.2337/diacare.24.1.131.

[221] Malone ML, Gennis V, Goodwin JS. Characteristics of diabetic ketoacidosis in older versus younger adults[J]. J Am Geriatr Soc, 1992, 40(11):1100‑1104. DOI: 10.1111/ j.1532‑5415.1992.tb01797.x.

[222] Wu L, Tsang V, Menzies AM, et al. Risk factors and characteristics of checkpoint inhibitor‑associated autoimmune diabetes mellitus (CIADM): a systematic review and delineation from type 1 diabetes[J]. Diabetes Care, 2023, 46(6):1292‑1299. DOI: 10.2337/dc22‑2202.

[223] Zhang W, Chen J, Bi J, et al. Combined diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state in type 1 diabetes mellitus induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors: underrecognized and underreported emergency in ICIs‑DM[J]. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 2022, 13:1084441. DOI: 10.3389/fendo.2022.1084441.

[224] Goldman A, Fishman B, Twig G, et al. The real‑world safety profile of sodium‑glucose co‑transporter‑2 inhibitors among older adults (≥ 75 years): a retrospective, pharmacovigilance study[J]. Cardiovasc Diabetol, 2023, 22(1): 16. DOI: 10.1186/ s12933‑023‑01743‑5.

[225] Bertoni AG, Hundley WG, Massing MW, et al. Heart failure prevalence, incidence, and mortality in the elderly with diabetes[J]. Diabetes Care, 2004, 27(3): 699‑703. DOI: 10.2337/diacare.27.3.699.

[226] Papakitsou I, Mavrikaki V, Petrakis E, et al. High incidence of heart failure in elderly patients with diabetes admitted in internal medicine department[J]. Atherosclerosis, 2021(331): e241. DOI: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2021.06.745.

[227] Boonman‑de Winter LJ, Rutten FH, Cramer MJ, et al. High prevalence of previously unknown heart failure and left ventricular dysfunction in patients with type 2 diabetes [J]. Diabetologia, 2012, 55(8): 2154‑2162. DOI: 10.1007/ s00125‑012‑2579‑0.

[228] Cavender MA, Steg PG, Smith SC Jr, et al. Impact of diabetes mellitus on hospitalization for heart failure, cardiovascular events, and death: outcomes at 4 years from the reduction of atherothrombosis for continued health (REACH) registry[J]. Circulation, 2015, 132(10): 923‑931. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.014796.

[229] Scirica BM, Bhatt DL, Braunwald E, et al. Saxagliptin and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus[J]. N Engl J Med, 2013, 369(14):1317‑1326. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1307684.

[230] Eurich DT, Weir DL, Majumdar SR, et al. Comparative safety and effectiveness of metformin in patients with diabetes mellitus and heart failure: systematic review of observational studies involving 34, 000 patients[J]. Circ Heart Fail, 2013, 6(3): 395‑402. DOI: 10.1161/ CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.000162.

[231] Tseng CH. Metformin use is associated with a lower risk of hospitalization for heart failure in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a retrospective cohort analysis[J]. J Am Heart Assoc, 2019, 8(21): e011640. DOI: 10.1161/ JAHA.118.011640.

[232] 中华医学会糖尿病学分会, 中华医学会内分泌学分会 . 中国成人 2 型糖尿病合并心肾疾病患者降糖药物临床应用专家共识[J]. 中华糖尿病杂志, 2020, 12(6):369‑381. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.cn115791‑20200419‑00233.

[233] Kutz A, Kim DH, Wexler DJ, et al. Comparative cardiovascular effectiveness and safety of SGLT‑2 inhibitors, GLP‑1 receptor agonists, and DPP‑4 inhibitors according to frailty in type 2 diabetes[J]. Diabetes Care, 2023, 46(11):2004‑2014. DOI: 10.2337/dc23‑0671.

[234] Ling X, Cummings SR, Mingwei Q, et al. Vertebral fractures in Beijing, China: the Beijing Osteoporosis Project[J]. J Bone Miner Res, 2000, 15(10):2019‑2025. DOI: 10.1359/ jbmr.2000.15.10.2019.

[235]Gilbert MP, Pratley RE. The impact of diabetes and diabetes medications on bone health[J]. Endocr Rev, 2015, 36(2):194‑213. DOI: 10.1210/er.2012‑1042.

[236] Pan Q, Chen H, Fei S, et al. Medications and medical expenditures for diabetic patients with osteoporosis in Beijing, China: a retrospective study[J]. Diabetes Res Clin Pract, 2023, 206:

110980. DOI: 10.1016/j. diabres.2023.110980.

[237] Dufour AB, Kiel DP, Williams SA, et al. Risk factors for incident fracture in older adults with type 2 diabetes: the Framingham Heart Study[J]. Diabetes Care, 2021, 44(7): 1547‑1555. DOI: 10.2337/dc20‑3150.

[238]Bonds DE, Larson JC, Schwartz AV, et al. Risk of fracture in women with type 2 diabetes: the Women′s Health Initiative Observational Study[J]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2006, 91(9):3404‑3410. DOI: 10.1210/jc.2006‑0614.

[239] Giangregorio LM, Leslie WD, Lix LM, et al. FRAX underestimates fracture risk in patients with diabetes[J]. J Bone Miner Res, 2012, 27(2): 301‑308. DOI: 10.1002/ jbmr.556.

[240] Tao Y, Meng E, Shi J, et al. Sulfonylureas use and fractures risk in elderly patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta‑analysis study[J]. Aging Clin Exp Res, 2021, 33(8): 2133‑2139. DOI: 10.1007/s40520‑020‑01736‑4.

[241] 中华医学会骨质疏松和骨矿盐疾病分会, 中华医学会内分泌学分会, 中华医学会糖尿病学分会, 等 . 糖尿病患者骨折风险管理中国专家共识[J]. 中华糖尿病杂志, 2019, 11(7):445‑456. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1674‑5809.2019.07.002.

[242] Won CW, Yoo HJ, Yu SH, et al. Lists of geriatric syndromes in the Asian-Pacific Geriatric Societies[J]. European Geriatric Medicine, 2013,4(5):335-338.

[243] Wang T, Feng X, Zhou J, et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus is associated with increased risks of sarcopenia and pre‑sarcopenia in Chinese elderly[J]. Sci Rep, 2016, 6: 38937. DOI: 10.1038/srep38937.

[244] Leenders M, Verdijk LB, van der Hoeven L, et al. Patients with type 2 diabetes show a greater decline in muscle mass, muscle strength, and functional capacity with aging

[J]. J Am Med Dir Assoc, 2013, 14(8): 585‑592. DOI: 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.02.006.

[245] Mori H, Kuroda A, Araki M, et al. Advanced glycation end‑products are a risk for muscle weakness in Japanese patients with type 1 diabetes[J]. J Diabetes Investig, 2017, 8(3):377‑382. DOI: 10.1111/jdi.12582.

[246] An HJ, Tizaoui K, Terrazzino S, et al. Sarcopenia in autoimmune and rheumatic diseases: a comprehensive review[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2020, 21(16):5678. DOI: 10.3390/

[247] 何清华, 孙明晓, 岳燕芬, 等. 老年糖尿病肌少症患者的代谢特点及膳食分析 [J]. 中华老年医学杂志 , 2019, 38(5): 552‑557. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254‑9026.2019.05.019.

[248] Kalyani RR, Corriere M, Ferrucci L. Age‑related and disease‑related muscle loss: the effect of diabetes, obesity, and other diseases[J]. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol, 2014, 2(10):819‑829. DOI: 10.1016/S2213‑8587(14)70034‑8.

[249] Batsis JA, Villareal DT. Sarcopenic obesity in older adults: aetiology, epidemiology and treatment strategies[J]. Nat Rev Endocrinol, 2018, 14(9): 513‑537. DOI: 10.1038/ s41574‑018‑0062‑9.

[250] Batsis JA, Mackenzie TA, Emeny RT, et al. Low lean mass with and without obesity, and mortality: results from the 1999—2004 national health and nutrition examination survey[J]. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 2017, 72(10): 1445‑1451. DOI: 10.1093/gerona/glx002.

[251] Chen LK, Woo J, Assantachai P, et al. Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia: 2019 consensus update on sarcopenia diagnosis and treatment[J]. J Am Med Dir Assoc, 2020, 21(3):300‑307.e2. DOI: 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.12.012.

[252] Hanlon P, Nicholl BI, Jani BD, et al. Frailty and pre‑frailty in middle‑aged and older adults and its association with multimorbidity and mortality: a prospective analysis of 493 737 UK Biobank participants[J]. Lancet Public Health, 2018, 3(7): e323‑e332. DOI: 10.1016/S2468‑2667(18) 30091‑4.

[253] Kong LN, Lyu Q, Yao HY, et al. The prevalence of frailtyamong community‑dwelling older adults with diabetes: a meta‑analysis[J]. Int J Nurs Stud, 2021, 119:103952. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.103952.

[254] Strain WD, Down S, Brown P, et al. Diabetes and frailty: an expert consensus statement on the management of older adults with type 2 diabetes[J]. Diabetes Ther, 2021, 12(5): 1227‑1247. DOI: 10.1007/s13300‑021‑01035‑9.

[255] Rodriguez‑Mañas L, Laosa O, Vellas B, et al. Effectiveness of a multimodal intervention in functionally impaired older people with type 2 diabetes mellitus[J]. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle, 2019, 10(4): 721‑733. DOI: 10.1002/ jcsm.12432.

[256] Umegaki H. Sarcopenia and frailty in older patients with diabetes mellitus[J]. Geriatr Gerontol Int, 2016, 16(3): 293‑299. DOI: 10.1111/ggi.12688.

[257] Yang Y, Hu X, Zhang Q, et al. Diabetes mellitus and risk of falls in older adults: a systematic review and meta‑analysis[J]. Age Ageing, 2016, 45(6): 761‑767. DOI: 10.1093/ageing/afw140.

[258] Chen JF, Zhang YP, Han JX, et al. Systematic evaluation of the prevalence of cognitive impairment in elderly patients with diabetes in China[J]. Clin Neurol Neurosurg, 2023, 225:107557. DOI: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2022.107557.

[259] Cukierman‑Yaffe T, Gerstein HC, Williamson JD, et al. Relationship between baseline glycemic control and cognitive function in individuals with type 2 diabetes and other cardiovascular risk factors: the action to control cardiovascular risk in diabetes‑memory in diabetes (ACCORD‑MIND) trial[J]. Diabetes Care, 2009, 32(2): 221‑226. DOI: 10.2337/dc08‑1153.

[260] Cukierman T, Gerstein HC, Williamson JD. Cognitive decline and dementia in diabetes‑‑systematic overview of prospective observational studies[J]. Diabetologia, 2005, 48(12):2460‑2469. DOI: 10.1007/s00125‑005‑0023‑4.

[261] Tomlin A, Sinclair A. The influence of cognition on self‑management of type 2 diabetes in older people[J]. Psychol Res Behav Manag, 2016, 9: 7‑20. DOI: 10.2147/ PRBM.S36238.

[262] Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician[J]. J Psychiatr Res, 1975, 12(3): 189-198. DOI: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6.

[263] Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal cognitive assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment[J]. J Am Geriatr Soc, 2005, 53(4):695‑699. DOI: 10.1111/j.1532‑5415.2005.53221.x.

[264] Sun M, Chen WM, Wu SY, et al. Metformin in elderly type 2 diabetes mellitus: dose‑dependent dementia risk reduction[J]. Brain, 2023: awad366. DOI: 10.1093/ brain/awad366.

[265] Zhou B, Zissimopoulos J, Nadeem H, et al. Association between exenatide use and incidence of Alzheimer′s disease[J]. Alzheimers Dement (N Y), 2021, 7(1):e12139. DOI: 10.1002/trc2.12139.

[266] Yang Y, Zhao JJ, Yu XF. Expert consensus on cognitive dysfunction in diabetes[J]. Curr Med Sci, 2022, 42(2): 286‑303. DOI: 10.1007/s11596‑022‑2549‑9.

[267] Chen Y, Qin J, Tao L, et al. Effects of Tai Chi Chuan on cognitive function in adults 60 years or older with type 2 diabetes and mild cognitive impairment in China: a randomized clinical trial[J]. JAMA Netw Open, 2023, 6(4): e237004. DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.7004.

[268] Alvarez‑Cisneros T, Roa‑Rojas P, Garcia‑Peña C. Longitudinal relationship of diabetes and depressive symptoms in older adults from Mexico: a secondary data analysis[J]. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care, 2020, 8(2): e001789. DOI: 10.1136/bmjdrc‑2020‑001789.

[269] Mendes R, Martins S, Fernandes L. Adherence to medication, physical activity and diet in older adults with diabetes: its association with cognition, anxiety and depression[J]. J Clin Med Res, 2019, 11(8):583‑592. DOI: 10.14740/jocmr3894.

[270] Kukreja D, Günther U, Popp J. Delirium in the elderly: current problems with increasing geriatric age[J]. Indian J Med Res, 2015, 142(6): 655‑662. DOI: 10.4103/0971‑5916.174546.

[271] O′ Brien H, Anne Kenny R. Syncope in the elderly[J]. Eur Cardiol, 2014, 9(1):28‑36. DOI: 10.15420/ecr.2014.9.1.28.

[272] Ooi WL, Hossain M, Lipsitz LA. The association between orthostatic hypotension and recurrent falls in nursing home residents[J]. Am J Med, 2000, 108(2):106‑111. DOI: 10.1016/s0002‑9343(99)00425‑8.

[273] Masaki KH, Schatz IJ, Burchfiel CM, et al. Orthostatic hypotension predicts mortality in elderly men: the Honolulu Heart Program[J]. Circulation, 1998, 98(21): 2290‑2295. DOI: 10.1161/01.cir.98.21.2290.

[274] Xin W, Lin Z, Mi S. Orthostatic hypotension and mortality risk: a meta‑analysis of cohort studies[J]. Heart, 2014, 100(5):406‑413. DOI: 10.1136/heartjnl‑2013‑304121.

[275] Shibao C, Grijalva CG, Raj SR, et al. Orthostatic hypotension‑related hospitalizations in the United States [J]. Am J Med, 2007, 120(11): 975‑980. DOI: 10.1016/j. amjmed.2007.05.009.

[276] Di Stefano C, Milazzo V, Totaro S, et al. Orthostatic hypotension in a cohort of hypertensive patients referring to a hypertension clinic[J]. J Hum Hypertens, 2015, 29(10):599‑603. DOI: 10.1038/jhh.2014.130.

[277] Kamaruzzaman S, Watt H, Carson C, et al. The association between orthostatic hypotension and medication use in the British Women′s Heart and Health Study[J]. Age Ageing, 2010, 39(1):51‑56. DOI: 10.1093/ageing/afp192.

[278] Maurer MS, Karmally W, Rivadeneira H, et al. Upright posture and postprandial hypotension in elderly persons [J]. Ann Intern Med, 2000, 133(7): 533‑536. DOI: 10.7326/0003‑4819‑133‑7‑200010030‑00012.

[279] Shibao C, Gamboa A, Diedrich A, et al. Acarbose, an alpha‑glucosidase inhibitor, attenuates postprandial hypotension in autonomic failure[J]. Hypertension, 2007, 50(1):54‑61. DOI: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.091355.

[280] Sacerdote C, Ricceri F. Epidemiological dimensions of the association between type 2 diabetes and cancer: a review of observational studies[J]. Diabetes Res Clin Pract, 2018, 143:369‑377. DOI: 10.1016/j.diabres.2018.03.002.

[281] Carstensen B, Read SH, Friis S, et al. Cancer incidence in persons with type 1 diabetes: a five‑country study of 9, 000 cancers in type 1 diabetic individuals[J]. Diabetologia, 2016, 59(5): 980‑988. DOI: 10.1007/ s00125‑016‑3884‑9.

[282] Orchard SG, Lockery JE, Broder JC, et al. Association of metformin, aspirin, and cancer incidence with mortality risk in adults with diabetes[J]. JNCI Cancer Spectr, 2023, 7(2):pkad017. DOI: 10.1093/jncics/pkad017.