Introduction

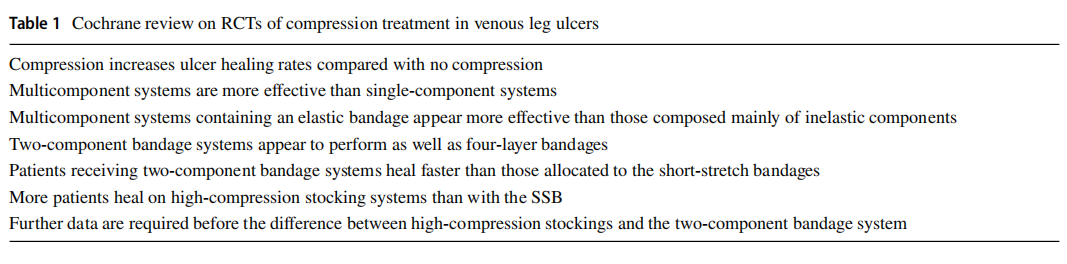

Compression therapy is the standard care for venous leg ulcers and its efficacy has been demonstrated in many RCTs and meta-analyses [1] (Table 1). It has been shown to play a crucial role in wound healing, particularly when edema is present regardless of aetiology. Compression therapy is also suggested for skin diseases with aetiologies that do not usually require compression. Compression stockings are recommended in the literature for the management of non-venous leg ulcers including cutaneous vasculitis in the lower extremities in order to reduce purpura, leg ulcers due to sickle cell anemia, and pyoderma gangrenosum. Although no studies exist in the literature, we believe that compression therapy in lower leg non-venous diseases is pathophysiologically appropriate without major adverse effects.

Compression Therapy: Mechanism of Action

According to the law of Laplace, compression pressure is directly proportional to the tension of the applied bandages and the number of layers and indirectly proportional to the radius of the limb. The compression affects all the deformable structures of the extremities: blood and lymphatic vessels and tissue edema. It has been demonstrated that in patients with chronic leg edema, the compression pressure is directly correlated with the reduction in edema with a pressure range of between 10 and 40 mmHg. Higher pressures led to an inverse correlation with less reduction in edema. Patients with lymphoedema of the arms showed a higher reduction in edema with less than 30 mmHg pressure compared to 50 mmHg [2]. This is due to the different action of compression regarding venular filtration and lymphatic drainage. The fluid filtration in the venules depends on the pressure gradient between the position-dependent intravenous pressure and the tissue pressure, and is therefore higher in the lower legs than the arms. The lymphatic drainage decreases when the external pressure is higher than that of the lymphatic pump [3]. A few studies have shown that compression reduces ambulatory venous hypertension [4]. Partsch demonstrated a significant reduction in ambulatory venous hypertension with inelastic bandages when exerting resting pressure of over 50 mm [5].

In arterial disease, appropriate compression based on the ankle brachial pressure index (ABPI) increases arterial flow (intermittent or moderate sustained pressure) and on the other hand, reduces arterial flow if the compression pressure exceeds the perfusion pressure [6].

Effect of Compression Therapy on Microcirculation and Cytokines

Several studies have shown that compression has an anti-inflammatory effect which could explain the prompt pain relief after the application of an appropriate bandage. Intermittent pneumatic pressure leads to increased shear stress in the microcirculation and releases anti-inflammatory, antithrombotic, and vasodilating mediators from the endothelial cells [7]. Some authors have shown that compression therapy reduces pro-inflammatory cytokines and metalloproteinase levels and increases anti-inflammatory cytokines [8]. These data explain the use of compression therapy in leg ulcers related to inflammatory diseases such as vasculitic ulcers and pyoderma gangrenosum.

Compression Therapy in Atypical Wounds on the Lower Leg

Although 75% of chronic leg ulcers are venous or mixed arteriovenous, atypical wounds make up a significant proportion of lower leg ulcers including inflammatory chronic wounds. Most of these ulcers are recalcitrant, difficult to treat, extremely painful and reduce the patient’s quality of life. The systemic treatment of the majority of atypical wounds is the gold standard therapy; however, good wound care plays a key role in wound management in terms of healing rate and the patient’s quality of life. The wound care regimen includes an appropriate compression bandaging system not only because the patients often have a secondary venous insufficiency but also because of the role of compression in inflammatory cytokine modulation (Figs. 1 and 2).

The literature lacks evidence regarding the use of compression therapy in lower leg inflammatory wounds. In 2019, Shavit and Alavi showed that there is limited evidence for the use of compression therapy in atypical lower leg wounds [9].

Pyoderma Gangrenosum

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) is a chronic neutrophilic dermatosis often associated with autoinflammatory diseases. The most frequent clinical variant is a chronic painful inflammatory ulcer commonly located on the lower extremities. One report showed the positive outcome of wound care including compression bandages leading to the complete healing of PG [10]. One study conducted on 100 patients affected by rheumatologic disease of whom 17 presented a PG on the lower leg showed successful results with compression therapy alone [11]. In our opinion, the active inflammatory phase of PG requires the systemic modulation of the autoinflammatory process with immunosuppressive drugs in combination with wound care and compression therapy [12••].

Adherence to treatment is a challenge for clinicians in these extremely painful wounds such as PG.

Necrobiosis Lipoidica

Necrobiosis lipoidica (NL) is a chronic granulomatosis disorder associated with diabetes and usually located on the pretibial region of the lower leg. It is very difficult to treat and the skin lesions can ulcerate. One report combined compression therapy with topical tacrolimus [13]. In our experience compression therapy is essential in order to prevent ulceration.

Cellulitis

The use of compression therapy in patients with cellulitis of the lower legs is based on the reduction in volume of soft tissue, and thus the least distance between the infected tissue and the capillaries and lymphatic vessels leading to a better supply of oxygen and antibiotics. This effect would be impaired if the blood flow is reduced by compression bandaging. Bojesen et al. showed that compression therapy does not compromise capillary flow rate in patients with cellulitis [14•]. Compression banding could play a key role as a supportive therapy in cellulitis of the lower legs; however, its role is still under debate. The clinical evidence is scarce and further studies are needed.

Cutaneous Vasculitis

To the best of our knowledge, there are no reports in the literature on the use of compression bandages in cutaneous vasculitis, which is characterized by vessel wall inflammation involving small and medium vessels. The clinical aspect is polymorphic which starts with purpura to small, multiple and painful ulcerations on dependent areas. The lesions are frequently located on the lower legs due to venous hypertension. Edema is not usually present. The main role of compression therapy is not to reduce edema but to remove inflammatory cells of the vessel walls in order to control the inflammatory process. In our experience, the empirical demonstration of this phenomenon is the complete cleaning of cutaneous purpura lesions on the inferior extremities after the application of compression bandaging (data at the press).

Compression bandaging could potentially be used to prevent the use of corticosteroids in small vessel cutaneous vasculitis relapse in patients with systemic diseases on immunosuppressive drugs. Further prospective studies are needed to confirm our hypothesis.

Epidermolysis Bullosa

The use of compression therapy in epidermolysis bullosa (EB) is controversial. The main action of treatment is about the role of compression wrap in keeping different types of skin substitutes in place [15]. A case series study on epidermolysis bullosa pruriginosa has shown evidence on patient quality of life, This is a rare variant of dystrophic EB with lesions occurring mainly on the lower leg with a lichenoid aspect [16].

Unna Boot

The Unna boot (UB) is a semi-solid gauze casting saturated with a mixture of zinc oxide, gum acacia, glycerol, castor oil, and deionized water. It is well established in the treatment of venous leg ulcers [17]. In a retrospective study, Lucia et al. [18] showed the efficacy of the UB in nineteen dermatological conditions in 136 patients. A total of 6% of patients were treated with UB alone and 94% received concomitant treatment. The results showed a positive response in 91.9% of treatment courses. A total of 7.4% of treatments were associated with the worsening of the disease. The most frequent dermatological diseases treated with the UB in association with topical and/or systemic treatment were as follows: actinic keratosis in association with concurrent topical therapies (16 patients), eruptive keratoacantoma (17), lipodermatosclerosis (12), prurigo nodularis (20), venous stasis dermatitis (14), and venous stasis ulcer (16). Two psoriasis patients were treated with a partial response. In our experience, compression treatment in psoriasis of the lower leg leads to a worsening of the disease due to the Koebner phenomenon.

The UB should be considered as an adjuvant treatment in diseases related to venous insufficiency but also in dermatological diseases in order to improve venous reflux, topical medication absorption, and reduce skin inflammation and maceration.

Arendsen et al. demonstrated the beneficial effect of copper stockings on lipodermatosclerosis in terms of the surface area involved but without improving symptoms [19]. Copper is known for its antimicrobial effects and is involved in wound healing by inducing vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) production and angiogenesis. It also promotes wound healing due to an increase in integrin expression, enhancement of fibrinogen stabilization, and up-regulation of several enzymes involved in matrix remodeling [20]. Suehiro et al. showed the beneficial effect of high-pressure compression therapy (> 40 mmHg) on nine patients affected by acute and subacute lipodermatosclerosis in terms of deformation of the skin and pain prevention [21••].

In our experience, the UB is a successful and inexpensive device in the management of allergic/irritative dermatitis and venous stasis dermatitis of the lower legs. An appropriate and prompt use of the UB can help to prevent the use of systemic corticosteroids with a synergic effect on topical treatment.

Conclusions

Compression therapy is considered to be the cornerstone for managing lower leg wounds, not only for venous leg ulcers caused by venous reflux and/or obstruction but also for lower leg wounds caused by other factors. Evidence of the efficacy of compression therapy on non-venous ulcers is limited but most experts apply compression therapy to lower extremity ulcers to improve wound healing [22]. The good results are probably related to the functional venous insufficiency in patients with lower extremity ulcers and to the potential role of compression in proinflammatory cytokine modulation. In our clinical practice, if not contraindicated, compression therapy can be beneficial for almost any lower leg ulcer procedure such as wound biopsy or wound excision.

We strongly recommend that further studies are carried out to confirm our assumption and establish an accurate range of pressure and compression components.

Funding Open access funding provided by Università di Pisa within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest The authors declare no competing interests.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

- Of importance

- • Of major importance

1.Mauck KF, Asi N, Elraiyah TA, et al. Comparative systematic review and meta-analysis of compression modalities for the promotion of venous ulcer healing and reducing ulcer recurrence. J Vasc Surg. 2014;60(2 Suppl.):71S–90S.

2. Damstra RJ, Partsch H. Compression therapy in breast cancer related lymphedema: a randomized, controlled comparative study of relation between volume and interface pressure changes. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49:1256–63.

3. Partsch H, Damstra RJ, Mosti G. Dose finding for an optimal compression pressure to reduce chronic edema of the extremitise. Int Anoigl.

4. ties. Int Angiol. 2011;30:527–33. O’Donnell TF Jr, Rosenthal DA, Callow AD, Ledig BL. Effect of elastic compression on venous hemodynamics in postphlebitic limbs. JAMA. 1979;242:2766–8.

5. Partsch H. Improving the venous pumping function in chronic venous insufficiency by compression as dependent on pressure and material. Vasa. 1984;13:58–64.

6. Mosti G, Iabichella ML, Partsch H. Compression therapy in mixed ulcers increases venous output and arterial perfusion. J Vasc Surg. 2012;55:122–8.

7. Chen AH, Frangos SG, Kilaru S, Sumpio BE. Intermittent pneumatic compression devices – physiological mechanisms of action. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2001;21:383–92.

8. Beidler SK, Douillet CD, Berndt DF, et al. Multiplexed analysis of matrix metalloproteinases in leg ulcer tissue of patients with chronic venous insufficiency before and after compression therapy. Wound Rep Regen. 2008;16:642–8.

9. Shavit E, Alavi A. Compression therapy for non-venous leg ulcers: current viewpoint. Int Wound J. 2019;16:1581–6.

10. Fioramonti P, Onesti MG, Fino P, Di Ronza S, Sorvillo V, Persichetti P. Feasibility of conservative medical treatment for pyoderma gangrenosum. In Vivo. 2012;26(1):157–9.

11. Chia HY, Tang MB. Chronic leg ulcers in adult patients with rheumatological diseases - a 7-year retrospective review. Int Wound J. 2014;11(6):601–4.

12.•• Janowska A, Oranges T, Fissi A, et al. PG-TIME: a practical approach to the clinical management of pyoderma gangrenosum. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(3). Describes a practical approach to pyoderma gangrenosum providing a useful algorithm including compression therapy.

13. Ginocchio L, Draghi L, Darvishian F, Ross FL. Refractory ulcerated necrobiosis lipoidica: closure of a difficult wound with topical tacrolimus. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2017;30(10):469–72.

14.• Bojesen S, Midttun M, Wiese L. Compression bandaging does not compromise peripheral microcirculation in patients with cellulitis of lower leg. Eur J Dermatol. 2019;29(4):396–400. Research study providing a clear cut explanation regarding the synergic effect of compression therapy on microcirculation by using several monitoring parameters.

15. Fivenson D, Scherschun L. Choucair M et al Graftskin therapy in epidermolysis bullosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48(6):886–92.

16. Kim W, Alavi A, Pope E, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa pruriginosa: Case series and review of the literature. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2015;14(2):196–9.

17. Paranhos T, et al. Assessment of the use of Unna boot in the treatment of chronic venous leg ulcers in adults: a systematic review protocol. BMJ Open. 2019; 9(12)e032091.

18. Lucia GS, Snyder A, Plante J, et al. Unna boot efficacy in dermatologic diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85(1):267–9.

19. Arendsen LP, Vig S, Thakar R, et al. Impact of copper compression stockings on venous insufficiency and lipodermatosclerosis: a randomized controlled trial. Phlebology. 2019;34(4):224–30.

20. Sen CK, Khanna S, Venojarvi M, et al. Copper-induced vascular endothelial growth factor expression and wound healing. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H1821–7.

21.•• Suehiro K, Morikage N, Takasuke H, et al. Compression therapy using bandages successfully manages acute or subacute lipodermatosclerosis. Ann Vasc Dis. 2019;12(1):77–9. Case series of patients successfully treated with compression therapy, with a long term follow-up and no recurrences of the lipodermatosclerosis.

22. Falanga V, Isserof R. Soulika A et al Chronic wounds. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2022;8(1):50.

Publisher's Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is excerpted from the Current Dermatology Reports by Wound World.