Introduction

Chronic wounds represent the largest direct medical cost of all skin conditions, costing nearly 9 billion USD in the United States annually [1]. A patient’s quality of life (QOL) can be as profoundly impaired by chronic wounds as by heart and renal disease [1]. Existing, comprehensive wound assessments evaluate varying wound characteristics, including amount of drainage, pain between and during dressing changes, odor, itching, bleeding, and impact of the wound on QOL. Evaluation of change in wound drainage helps inform clinicians regarding treatment efficacy.

Many drainage assessments are currently tailored to assess post-surgical wounds. However, several other cutaneous conditions involve wound drainage, including inflammatory skin disorders such as hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) and pyoderma gangrenosum (PG), neoplastic diseases such as malignant tumors, and chronic ulcers, including vascular, inflammatory, and rheumatologic ulcers [1]. Although studies have examined the impact of drainage on patient QOL, there is a lack of validated, targeted tools to specifically measure drainage in patients with inflammatory skin disorders such as HS and PG [2]. The aim of this study is to review existing tools used to assess drainage and highlight the lack of and need for global drainage measures in inflammatory draining skin conditions.

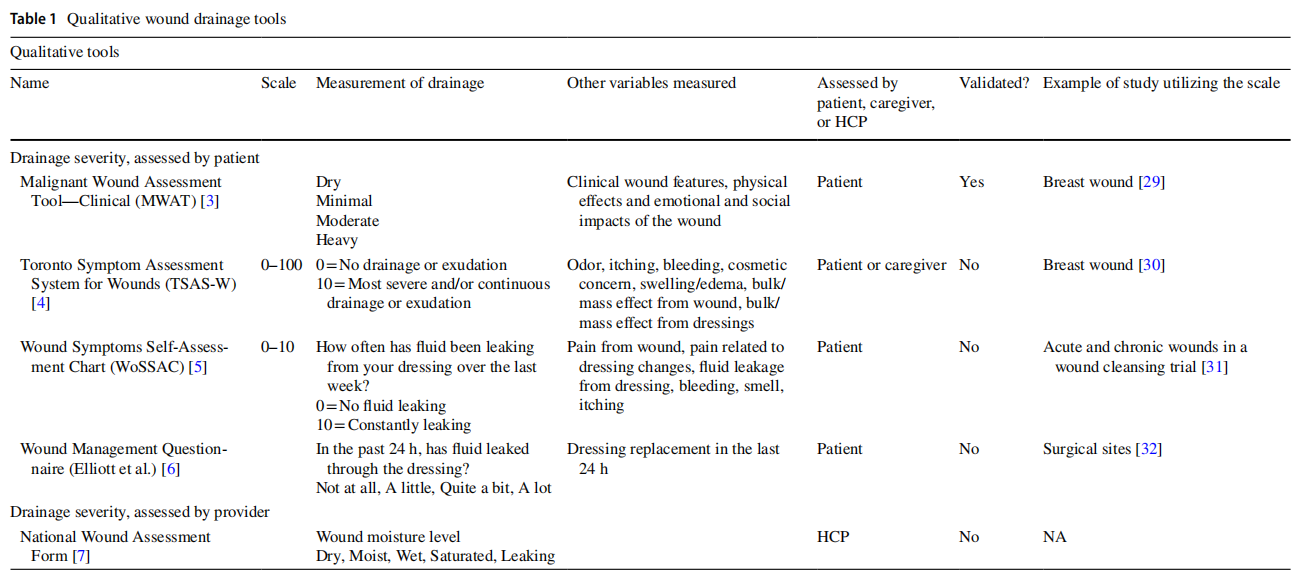

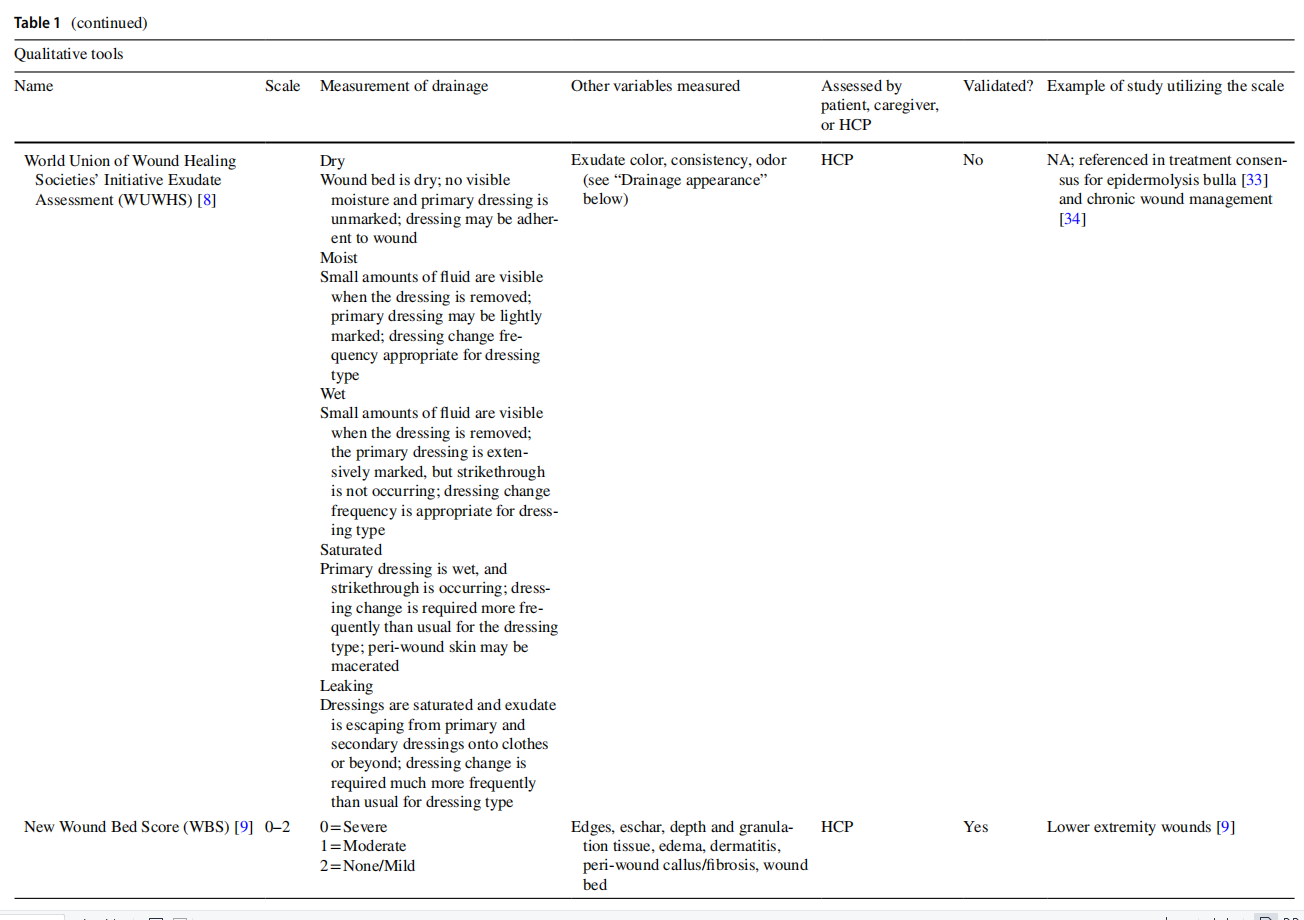

Qualitative wound drainage tools Assessment of drainage severity

Several measures have been created for patients to qualitatively assess drainage severity on categorical or numerical scales (Table 1). An example of a categorical scale is the Malignant Wound Assessment Tool (MWAT), a validated measure with domains including clinical wound features (i.e., wound location, classification, and edema) and physical, emotional, and social impact of the wound [3]. Regarding drainage, patients are asked to rate the severity as “dry, minimal, moderate, or heavy.” Numerical rating scales ask patients to rate drainage severity, often on a scale of 0–10. Zero represents no drainage, and “10” represents the worst drainage; “10” may be defined in different ways depending on the measure. As an example, the Toronto Symptom Assessment System for Wounds (TSAS-W) defines “10” as “most severe and/or continuous drainage or exudation.” [4] Some numerical scales have a descriptor that accompanies each number in the scale. Finally, another measure of drainage severity is qualitatively evaluating the amount of leakage from dressings. The Wound Symptoms Self-Assessment Chart queries how often fluid has been leaking from a patient’s dressing over the last week on a scale of 0–10, with “10” defined as “constantly leaking” [5]. Similarly, the Wound Management Questionnaire asks patients whether fluid has leaked through their dressing, from “not at all,” “a little,” “quite a bit,” to “a lot” [6].

Similarly, both categorical and numerical tools exist for healthcare providers (HCPs) to qualitatively assess drainage severity (Table 1). Categorical tools include the National Wound Assessment Form, which assesses wound moisture level as dry, moist, wet, saturated, or leaking [7]. The World Union of Wound Healing Societies’ (WUWHS) Initiative Exudate Assessment uses the same categorical rating scale for drainage, but provides definitions for each rating based on qualitative estimates of fluid amount, saturation of dressing, and frequency of dressing changes [8]. Several tools grade drainage on a numerical scale with a descriptor provided for each number. For most of these measures, “0” represents no drainage. Greatest severity is defined as “severe” in the New Wound Bed Score [9], “smelly exudate” in the Tissue, Inflammation/Infection, Moisture, Edge/Epithelialization (TIME) score [10], “heavy” in the Pressure Ulcer Scale for Healing tool [11], and “copious” in the Leg Ulcer Measurement Tool [12].

Assessment of drainage appearance

In addition to assessing severity of drainage, certain tools also describe other characteristics of drainage, including viscosity, color, and the presence of odor. For example, MEASURE and MWAT can be used to evaluate drainage viscosity in categories ranging from serous, serosanguineous, to purulent [3, 13]. Drainage color is included in WUWHS, including options of red/pink, yellow/green, to brown/gray [8]. The presence of odor is a component of the TSASW and WUWHS measures [4, 8]. The Bates–Jenson Wound Assessment Tool (BWAT) scores exudate type on a scale of 1 (bloody) to 5 (foul purulent) based on a composite evaluation of viscosity, color, and the presence or absence of odor [14].

Advantages and disadvantages of qualitative methods

Qualitative wound drainage measures do not require any equipment and are less burdensome to complete as compared to quantitative measures. Ease of use of these tools may encourage more frequent assessments of drainage, which is an important component of evaluating treatment efficacy for inflammatory skin conditions with drainage. Categorical and numerical scales for drainage amount can help track disease status and direction of change for individual patients. Disadvantages include the lack of specific criteria for each numerical or categorical value. Even for tools that define each possible response, user interpretations may vary since the definitions are not based on quantitative criteria, and this may reduce inter-rater reliability. Thus, comparing drainage status between patients based on qualitative responses is difficult (e.g., one patient’s “severe” may be another patient’s “moderate”). To this end, some clinical trials specifically track change in exudate status, as opposed to the exudate amount itself, noted as decreased, equal/ unchanged, or increased [15].

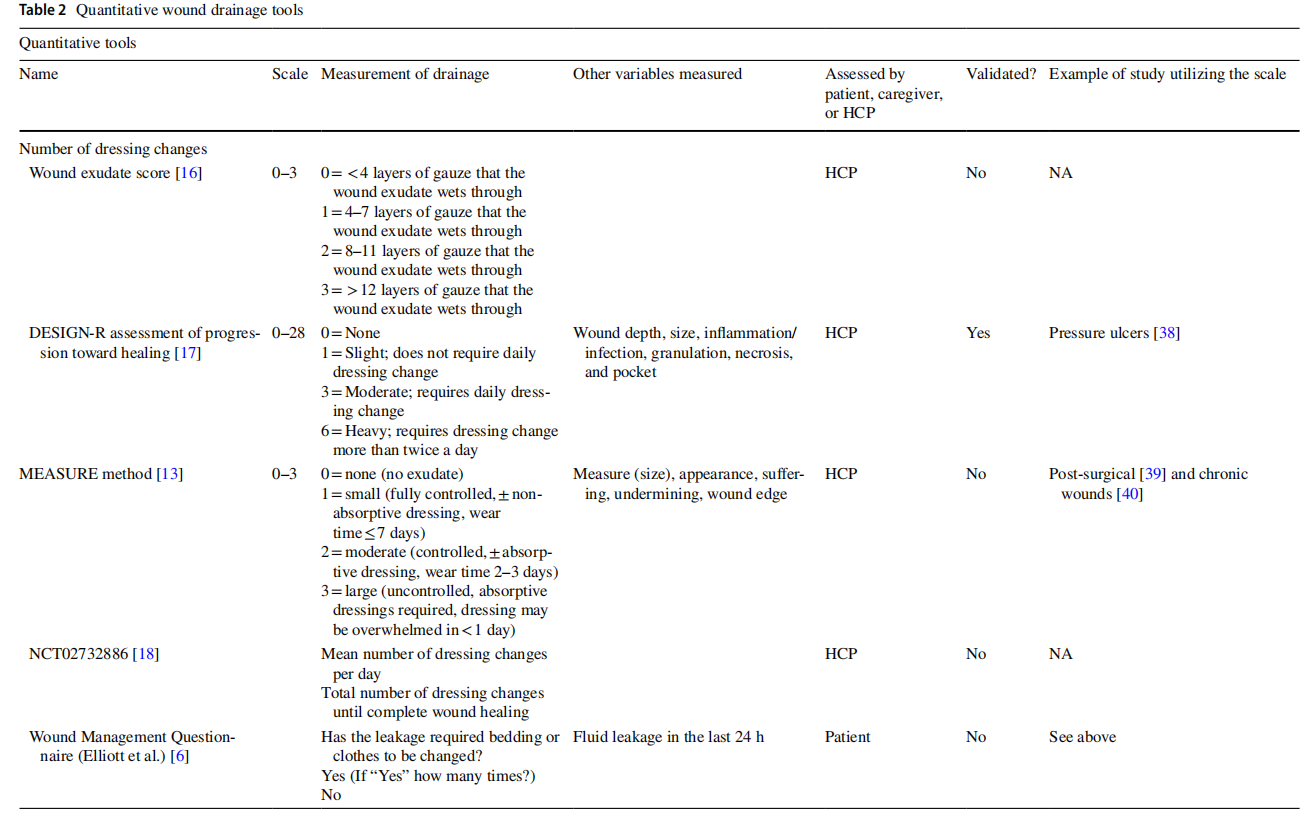

Quantitative wound drainage tools Assessment of drainage based on wound dressing

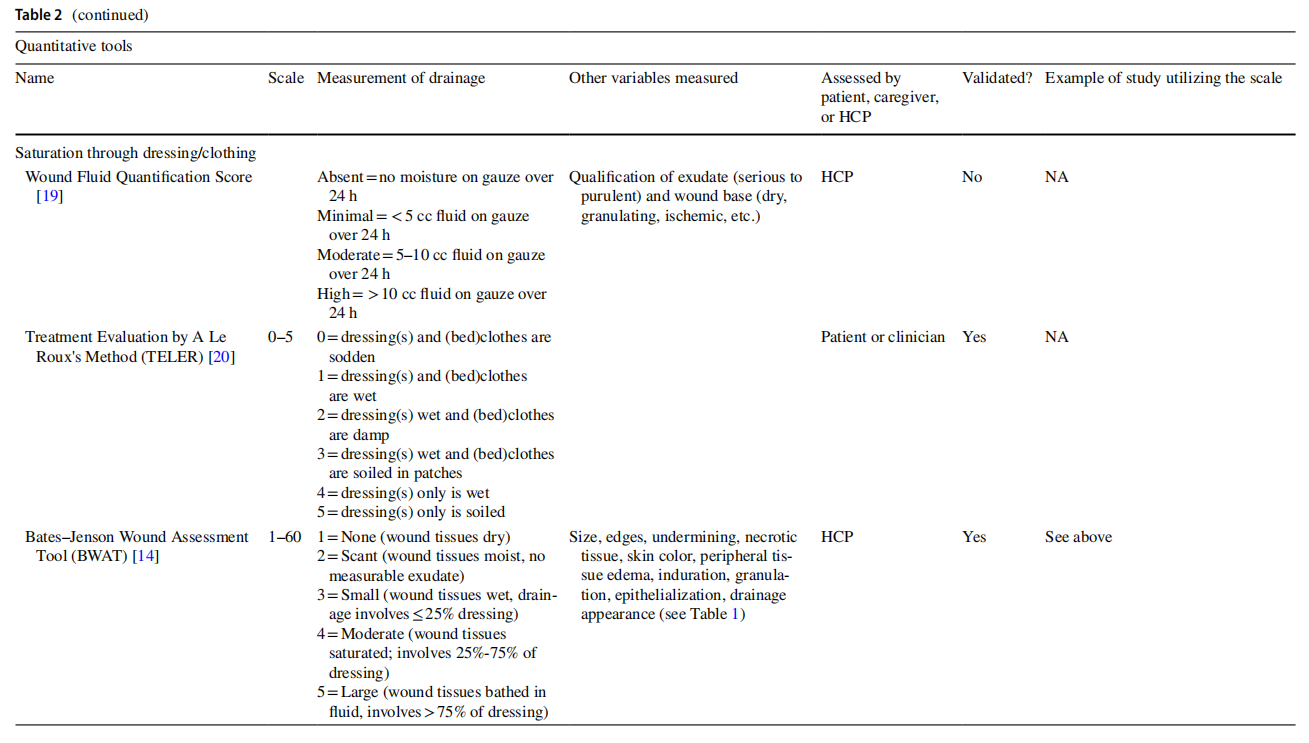

Several quantitative wound drainage tools use dressings as a means of drainage measurement (Table 2). Most are clinician-reported outcomes. Strategies include measuring the layers of gauze a wound soaks through, the number of dressing changes per day, and the degree of saturation on a dressing or on clothing. In the wound exudate score, users count the layers of gauze soaked through by exudate. The score ranges from 0 to 3, with 3 defined as>12 layers of gauze soaked through [16]. Examples of measures that count the number of dressing changes include DESIGN-R and MEASURE. DESIGN-R evaluates frequency of dressing changes from 0 (none) to 6 (more than twice a day) [17]. MEASURE takes into consideration the wear time of a dressing in days and whether nonabsorptive or absorptive dressings are required [13]. Some clinical trials calculate the mean number of dressing changes per day and the total number of dressing changes needed until a wound has completely healed [18]. The Wound Management Questionnaire is a patient tool that asks patients whether leakage has required bedding or clothes to be changed, and if so, how many times [6].

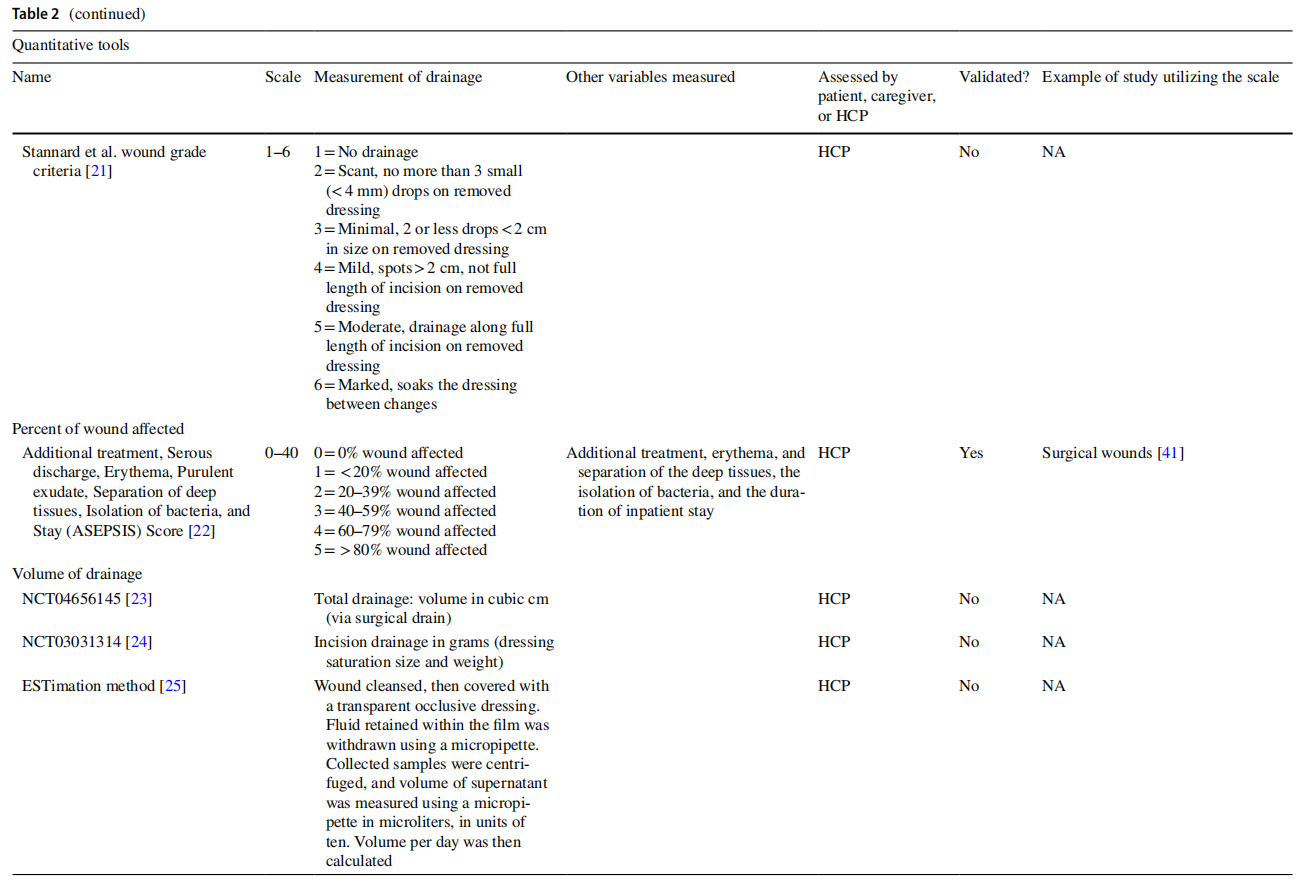

Different tools evaluate the degree of saturation on dressing or clothing. The Wound Fluid Quantification Score has an HCP rate drainage as absent, minimal, moderate, or high, based on the volume in milliliters of fluid on gauze over 24 h [19]. The Treatment Evaluation by A Le Roux's (TELER) Method evaluates whether dressings and/or clothes are damp, wet, or sodden [20]. BWAT examines the moisture of wound tissues (dry, moist, wet, saturated, or bathed in fluid) and area of drainage involvement of dressing (ranging from no measurable exudate to exudate involving>75% of dressing) [14]. Stannard et al. quantify drainage via the size of exudate area involvement in centimeters on the removed dressing [21].

Assessment of drainage based on amount of wound affected

One tool that assesses drainage severity based on the amount of wound affected is the validated Additional treatment, Serous discharge, Erythema, Purulent exudate, Separation of deep tissues, Isolation of bacteria, and Stay (ASEPSIS) Score (Table 2). Utilizing a numerical scale of 0 to 5, it examines serous and purulent exudate separately and defines each score based on proportion of the wound affected (i.e., a score of 5 indicates>80% wound affected) [22].

Other quantitative measures of drainage

Some clinical trials seek to measure the exact volume of drainage. These methods may include measurement in cubic cm of drainage collected in surgical drains [23] or calculating the weight difference of a saturated dressing [24]. The ESTimation method uses a micropipette to recover fluid from a dressing that was occluded over the wound. The sample is centrifuged to remove cell debris, and then, the volume of supernatant is measured in microliters. The volume per hour is then multiplied by 24 to calculate drainage over 24 h [25].

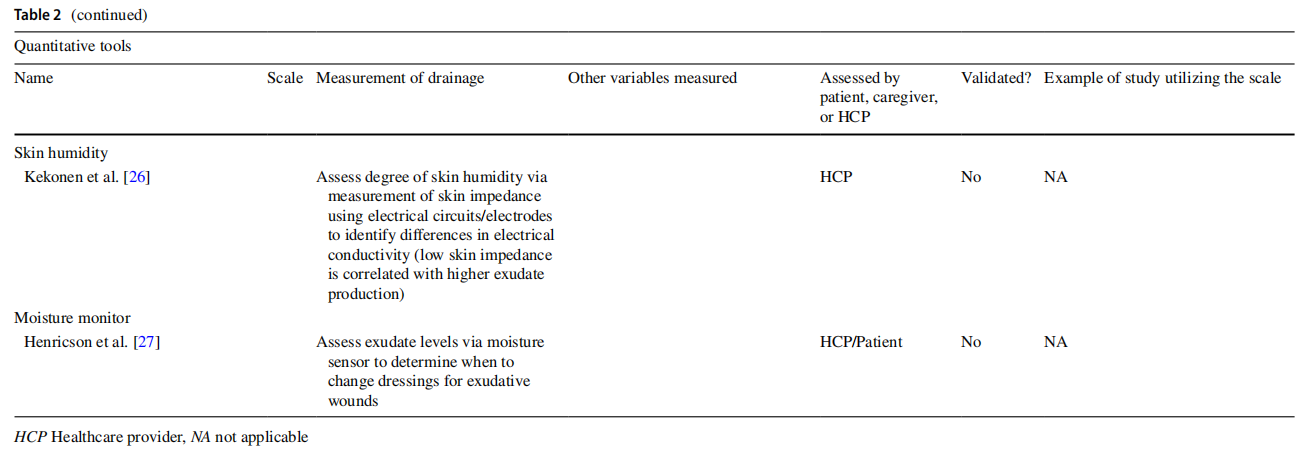

Recent studies have examined whether skin impedance values, which reflect the response of skin regions to applied electrical currents, may help characterize drainage. Kekonen et al. described the utility of using electrodes to generate skin impedance values to assess degree of skin humidity [26]. Low skin impedance was correlated with higher exudate production. Henricson et al. described using a moisture sensor to assess exudate levels to guide when to change wound dressings [27].

Advantages and disadvantages of quantitative methods

Quantitative tools for wound drainage severity measurement have less inter-rater variability as compared to qualitative methods. They not only enable the evaluation of drainage status and drainage response to treatment of individual patients, but also allow more reliable comparisons regarding drainage severity and treatment response across different patients. However, quantitative methods impart greater responder burden on the clinician and patient, sometimes requiring physical equipment. In addition, unless exact measurement of drainage is sought, surrogate methods of measurement may still impart inter-rater variability. For example, measures based on number of dressing changes per day may differ depending on different thresholds patients have for changing their dressing. Measures that examine dressing saturation depend on how the dressing is affixed and the type of dressing used. Of the measures discussed in this paper, only DESIGN-R, TELER, and BWAT have been validated in studies.

Lack of global drainage measures in chronic inflammatory skin conditions

Using HS as an example of a chronic inflammatory draining skin disease, there is one study in the literature that evaluates efficacy of wound dressings in HS patients, which asked participants to rate drainage severity from 1 to 4, defined as 1 (no), 2 (a little), 3 (moderate), or 4 (a lot of drainage) [28]; however, this was not a validated measure. Another measure, the Hidradenitis Suppurativa Odor and Drainage Scale (HODS), asks patients to rate both the usual amount and worst amount of drainage from their HS for specific anatomic locations, including head/neck, armpits, trunk, groin, buttocks, genital/perianal area, and other areas. The 5-point categorical scale for HODS ranges from “no drainage” to “very severe drainage,” and each is defined based on the wear time of dressings. Though specific for HS, HODS does not include a simple global drainage measure. PG, another chronic draining inflammatory skin condition, also lacks a specific global measure for drainage.

Discussion

Draining skin lesions greatly influence the morbidity of patients and constitute a significant clinical problem. However, the clinimetrics of drainage are overall poorly developed. Although there are various qualitative and quantitative wound drainage measurements that are in use as clinical tools or have been used in clinical trials, many of the existing scales have not been validated in robust studies.

There is currently a lack of a global, validated tool assessing wound drainage in inflammatory skin disorders. Several of the existing wound drainage measures are designed for surgical wounds and pressure ulcers, and these measures are not readily applicable to inflammatory skin conditions. For instance, measuring the distribution of drainage in a wound bed is difficult in a disease like HS where drainage is often sequestered in tunnels. Characterizing drainage viscosity as a measure of drainage severity is also less relevant for noninfectious, inflammatory skin conditions.

The lack of a specific and validated global drainage tool for inflammatory skin diseases is a barrier to assessment of this important outcome. More studies should investigate the development of a succinct drainage measure in skin diseases where drainage is a prominent, burdensome symptom. This would allow for improved monitoring of meaningful treatment response in clinical trials as well as in clinical settings.

Author contributions TS and SP collected data and wrote the main manuscript text. LRT, SD, AG, SDG, JSK, BMM, PTR, BV, KZ, and GBEJ edited the manuscript. JLH led the project. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding Open access funding provided by SCELC, Statewide California Electronic Library Consortium. This article has no funding source.

Declarations

Conflict of interest JLH is on the Board of Directors for the Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundation, has served as a consultant for Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, and UCB, and has served as a consultant and speaker for AbbVie. LT reports personal fees from UCB, non-financial support from AbbVie and Janssen-Cilag, grants from Regeneron, and is co-copyright holder of HiSQOL. SD is on the Board of Directors for the Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundation, has served as an investigator for AbbVie, Pfzer, Novartis, and UCB, and has served as a consultant and speaker for AbbVie. AG is an advisor for AbbVie, Aclaris Therapeutics, Anaptys Bio, Aristea Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Incyte, InfaRx, Insmed, Janssen, Novartis, Pfzer, UCB, Union Therapeutics, and Viela Biosciences, and receives honoraria. AG receives research grants from AbbVie, UCB and National Psoriasis Foundation. AG receives research grants from AbbVie, UCB, and National Psoriasis Foundation. AG is co-copyright holder of the HS-IGA and HiSQOL instruments. JSK is the President of the Hi-dradenitis Suppurativa Foundation. AbbVie: Consultant, Speaker, Advisory Board (Honoraria), ChemoCentryx, Incyte, Janssen, Novartis, UCB: Consultant (Honoraria). BMG has received fees from Novartis. GBJ reports grants and personal fees from AbbVie, personal fees from Coloplast, personal fees from Chemocentryx, personal fees from LEO pharma, grants from LEO Foundation, grants from Afyx, personal fees from Incyte, grants and personal fees from InfaRx, grants from Janssen-Cilag, grants and personal fees from Novartis, grants and personal fees from UCB, grants from CSL Behring, grants from Regeneron, grants from Sanofi, personal fees from Kymera, personal fees from VielaBio, outside the submitted work. There was no financial transaction for the preparation of this manuscript. All other authors report no conflicts of interest.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

References

1. Powers JG, Higham C, Broussard K, Phillips TJ (2016) Wound healing and treating wounds: chronic wound care and management. J Am Acad Dermatol 74(4):607–625

2. Montero-Vilchez T, Diaz-Calvillo P, Rodriguez-Pozo JA, CuencaBarrales C, Martinez-Lopez A, Arias-Santiago S et al (2021) The burden of Hidradenitis suppurativa signs and symptoms in quality of life: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(13):6709

3. Schulz V, Kozell K, Biondo PD, Stiles C, Martins L, Tonkin K et al (2009) The malignant wound assessment tool: a validation study using a Delphi approach. Palliat Med 23(3):266–273

4. Maida V, Ennis M, Kuziemsky C (2009) The Toronto Symptom Assessment System for wounds: a new clinical and research tool. Adv Skin Wound Care 22(10):468–474

5. Naylor W. Part 2: Symptom self-assessment in the management of fungating wounds [Internet]. Available from: http://www.world widewounds.com/2002/july/ Naylor-Part2/Wound-AssessmentTool.html. Cited 17 Apr 2022

6. Elliott D, Bluebelle Study Group (2017) Developing outcome measures assessing wound management and patient experience: a mixed methods study. BMJ Open 7(11):e016155

7. Fletcher J (2010) Development of a new wound assessment form. Wounds UK 1:6

8. World Union of Wound Healing Societies (WUWHS) Consensus Document. WUWHS Consensus Document: Wound Exudate, effective assessment and management. 2007; Available from:

http://www.woundsinternational.com

9. Falanga V, Saap LJ, Ozonof A (2006) Wound bed score and its correlation with healing of chronic wounds. Dermatol Ther 19(6):383–390

10. Guarro G, Cozzani F, Rossini M, Bonati E, Del Rio P (2021) The modified TIME-H scoring system, a versatile tool in wound management practice: a preliminary report. Acta Biomed 92(4):e2021226

11. Gardner SE, Frantz RA, Bergquist S, Shin CD (2005) A prospective study of the pressure ulcer scale for healing (PUSH). J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 60(1):93–97

12. Woodbury MG, Houghton PE, Campbell KE, Keast DH (2004) Development, validity, reliability, and responsiveness of a new leg ulcer measurement tool. Adv Skin Wound Care 17(4 Pt 1):187–196

13. Keast DH, Bowering CK, Evans AW, Mackean GL, Burrows C, D’Souza L (2004) MEASURE: a proposed assessment framework for developing best practice recommendations for wound assessment. Wound Repair Regen 12(3 Suppl):S1-17

14. Bates-Jensen BM, McCreath H, Patlan A, Harputlu D (2019) Reliability of the Bates-Jensen Wound Assessment Tool (BWAT) for pressure injury assessment: the pressure ulcer detection study. Wound Repair Regen 27(4):386–395

15. Evaluation of Exufiber Ag+ and Other Gelling Fibre Dressings (NCT03249909) [Internet]. Clinicaltrials.gov. Available from: clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04656145

16. Lu B, Du J, Wu X (2021) The effects of modified Buzhong Yiqi decoction combined with Gangtai ointment on the wound healing and anal function in circumferential mixed hemorrhoid patients. Am J Transl Res 13(7):8294–8301

17. Matsui Y, Furue M, Sanada H, Tachibana T, Nakayama T, Sugama J et al (2011) Development of the DESIGN-R with an observational study: an absolute evaluation tool for monitoring pressure ulcer wound healing. Wound Repair Regen 19(3):309–315

18. Betafoam Diabetes Mellitus Foot Study (NCT02732886) [Internet]. Clinicaltrials.gov. Available from: clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04656145

19. Mulder GD (1994) Quantifying wound fluids for the clinician and researcher. Ostomy Wound Manag 40(8):66–69

20. Browne N, Grocott P, Cowley S, Cameron J, Dealey C, Keogh A et al (2004) Woundcare Research for Appropriate Products (WRAP): validation of the TELER method involving users. Int J Nurs Stud 41(5):559–571

21. Stannard JP, Robinson JT, Anderson ER, McGwin G, Volgas DA, Alonso JE (2006) Negative pressure wound therapy to treat hematomas and surgical incisions following high-energy trauma. J Trauma 60(6):1301–1306

22. Copanitsanou P, Kechagias VA, Galanis P, Grivas TB, Wilson P (2019) Translation and validation of the Greek version of the “ASEPSIS” scoring method for orthopaedic wound infections. Int J Orthop Trauma Nurs 33:18–26

23. The Efficacy of Chlorhexidine Gluconate Gel Dressing in Preventing Surgical Drain Site Infection (NCT04656145) [Internet]. Clinicaltrials.gov. Available from: clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/ NCT04656145

24. Comparison of Knotless Barbed Suture and Standard Suture in Knee Replacement Patients (NCT03031314) [Internet]. Clinicaltrials.gov. Available from: clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/ NCT03031314

25. Iizaka S, Sanada H, Nakagami G, Koyanagi H, Konya C, Sugama J (2011) Quantitative estimation of exudate volume for fullthickness pressure ulcers: the ESTimation method. J Wound Care 20(10):453–454 (458–63)

26. Kekonen A, Bergelin M, Eriksson JE, Vaalasti A, Ylänen H, Viik J (2017) Bioimpedance measurement based evaluation of wound healing. Physiol Meas 38(7):1373–1383

27. Henricson J, Sandh J, Iredahl F (2021) Moisture sensor for exudative wounds—a pilot study. Skin Res Technol 27(5):918–924

28. Schneider C, Sanchez DP, MacQuhae F, Stratman S, Lev-Tov H (2022) Wound dressings improve quality of life for hidradenitis suppurativa patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 86(2):450–453

29. Rupert KL, Fehl AJ (2020) A patient-centered approach for the treatment of fungating breast wounds. J Adv Pract Oncol 11(5):503–510. https://doi.org/10.6004/jadpro. 2020.11.5.6.

(Epub 2020 Jul 1. PMID: 32974074; PMCID: PMC7508249)

30. Construction and Effect Evaluation of Malignant Fungating Wounds Care Regimen for Breast Cancer Patients (NCT05457309) [Internet]. Clinicaltrials.gov. Available from: clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05457309

31. Is Pressurized Irrigation an Effective Alternative to Swabbing for Wound Cleansing? (NCT01885273) [Internet]. Clinicaltrials.gov. Available from: clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01885273

32. NIHR Global Health Research Unit on Global Surgery (2021) Feasibility and diagnostic accuracy of Telephone Administration of an adapted wound heaLing QuestiONnaire for assessment for surgical site infection following abdominal surgery in low and middle-income countries (TALON): protocol for a study within a trial (SWAT). Trials 22(1):471. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063- 021-05398-z. (Published 2021 Jul 21)

33. Pope E, Lara-Corrales I, Mellerio J et al (2012) A consensus approach to wound care in epidermolysis bullosa. J Am Acad Dermatol 67(5):904–917. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad. 2012.01. 016

34. Eriksson E, Liu PY, Schultz GS et al (2022) Chronic wounds: treatment consensus. Wound Repair Regen. 30(2):156–171. https://doi.org/10.1111/wrr.12994

35. Cereda E, Gini A, Pedrolli C, Vanotti A (2009) Disease-specific, versus standard, nutritional support for the treatment of pressure ulcers in institutionalized older adults: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 57(8):1395–1402. https://doi.org/10. 1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02351.x

36. Sriram S, Sankaralingam R, Mani M, Tamilselvam TN (2016) Autologous platelet rich plasma in the management of non-healing vasculitic ulcers. Int J Rheum Dis 19(12):1331–1336. https://doi. org/10.1111/1756-185X.12914

37. Kheiri A, Amini S, Javidan AN, Saghafi MM, Khorasani G (2017) The effects of Alkanna tinctoria Tausch on split-thickness skin graft donor site management: a randomized, blinded placebo-controlled trial. BMC Complement Altern Med 17(1):253. https://doi. org/10.1186/s12906-017-1741-0. (Published 2017 May 8)

38. Shimura T, Nakagami G, Ogawa R et al (2022) Incidence of and risk factors for self-load-related and medical device-related pressure injuries in critically ill patients: a prospective observational cohort study. Wound Rep Reg 30(4):453–467. https://doi.org/10. 1111/wrr.13022

39. Hassan A, Ahmed E, Ghalwash D, Elarab AE (2021) Clinical comparison of MEBO and hyaluronic acid gel in the management of pain after free gingival graft harvesting: a randomized clinical trial. Int J Dent 2021:2548665. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/2548665. (Published 2021 Aug 14)

40. Silva LG, Albuquerque AV, Pinto FCM, Ferraz-Carvalho RS, Aguiar JLA, Lins EM (2021) Bacterial cellulose an effective material in the treatment of chronic venous ulcers of the lower limbs. J Mater Sci Mater Med 32(7):79. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10856-021-06539-1

41. Siah CJ, Childs C (2012) A systematic review of the ASEPSIS scoring system used in non-cardiac-related surgery. J Wound Care 21(3):124–130. https://doi.org/10.12968/jowc. 2012.21.3.124

Publisher's Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is excerpted from the Archives of Dermatological Research by Wound World.