Definition

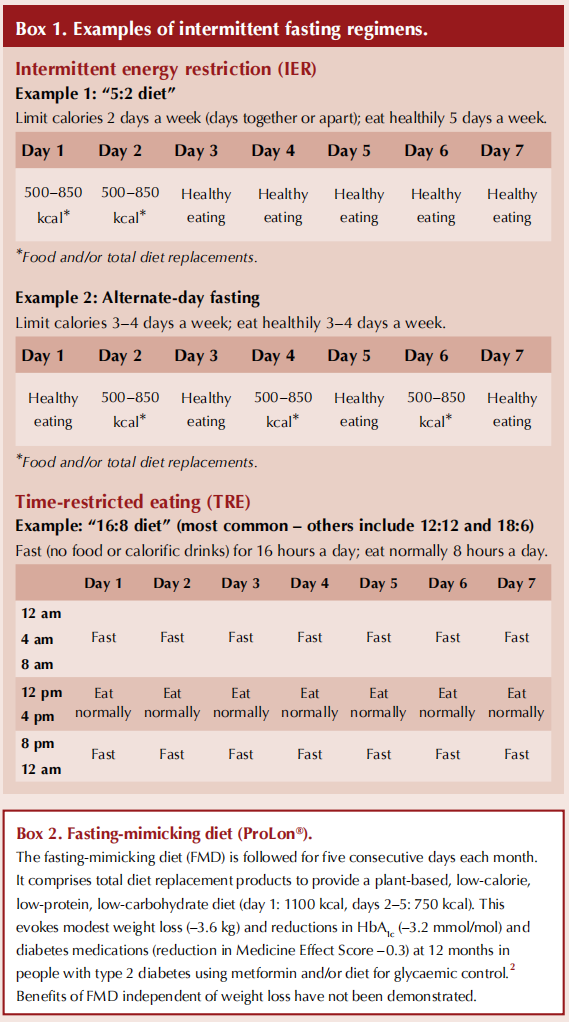

The two most popular forms of intermittent fasting are intermittent energy restriction (IER) and time-restricted eating (TRE) (See Box 1), which are likely to have different effects on weight and glycaemic control. Other approaches include the commercial fasting-mimicking diet (FMD), which utilises complete meal-replacement products (see Box 2).

Intermittent energy restriction (IER)

● 1–4 days of low energy (calorie) intake per week. Examples include the 5:2 diet (two low-calorie days per week) or alternate-day fasting (3–4 low-calorie days per week).

● These diets are not feast-or-famine, as typically portrayed. Low-calorie days comprise 500–850 kcal/day. Other days usually require healthy eating (i.e. a Mediterranean or American Heart Association diet – see Resources).

● Low-calorie days are usually food-based. Popular commercial, non-evidence-based versions allow a free choice of foods within the calorie allowance. However, most researched intermittent diets promote satiety by advising at least 50 g protein per day and high-fibre foods. Low-calorie days may also utilise 3–4 total diet replacement products (e.g. shakes/soups) per day, +/– vegetables, which typically provide a nutritionally complete diet at ~850 kcal/day.

Time-restricted eating (TRE)

●TRE reduces the typical eating window from 14–16 hours/day to 6–12 hours/day, and extends the typical fasting period from 8–10 hours/day to 12–18 hours/day, on a daily or near-daily basis.

● Dietary intake in the eating window is often unlimited. Non-calorie fluids, including diet drinks, are usually allowed during fasting hours.

Potential benefits for individuals with overweight and obesity

Mechanism of impact

● Spells of energy restriction (IER) or total fast (TRE) result in weight loss if overall calorie intake is reduced.

● There may also be weight-independent benefits to systemic and cellular metabolism, potentially linked to the switch from carbohydrate to fat metabolism, which can increase insulin sensitivity, reduce oxidative stress and inflammation, and promote autophagy (the cleaning out of damaged cells to maintain optimal cell function).3 The precise duration and degree of energy restriction required to elicit these responses is unknown.

Weight loss and metabolic effects

●IER (5:2 or alternate-day fasting) amongst people with overweight/obesity, with or without type 2 diabetes, achieves slightly better weight loss (~7%) compared with daily calorie restriction (5%) in the short term (studies of <6 months), but weight loss is comparable in the longer term (~5–6%).4

➤ IER leads to similar reductions in glycaemic and other metabolic effects to daily diets,4 with some evidence for improved post-prandial lipid metabolism.5

●TRE often leads to a reduction in calorie intake of 200–300 kcal/day. However, it is associated with more modest weight loss than IER: around 3% in the short term and 1% in the long term.6,7

➤ There are modest improvements in glycaemic parameters, which may be attributed to energy deficit and weight loss rather than food timing.

➤ More healthy profiles are seen with eating windows earlier in the day, which avoids the potential adverse metabolic effects of late-night eating, but this eating pattern can be disruptive to family life and socialising.8

Remission of type 2 diabetes

● The modest weight loss with IER (~7%) and TRE (~3%) means that they are unlikely to be as effective for diabetes remission as a daily low-calorie diet of 850 kcal/day over 8–12 weeks, currently being piloted by the National Health Service in the UK,9 which results in around 10% weight loss.

● Remission may be achieved in individuals who achieve and maintain large weight loss with IER (e.g. 15% of participants in the MIDDAS study10).

● There are no studies of TRE and diabetes remission.

Prediabetes and TRE

● Early TRE might improve glycaemic control in people with prediabetes (3–6-hour eating window, with dinner before 3.00 pm), with weight-independent benefits on insulin sensitivity, beta-cell responsiveness, blood pressure, oxidative stress and post-prandial glucose metabolism.11,12

Gestational diabetes (GDM)

● The 5:2 diet has been studied in women with a history of GDM and was comparable to a standard daily diet for weight loss and glycaemic measurements.13

● A small feasibility study is currently testing the acceptability and safety of a 5:2 diet with two non-consecutive days of 1000 kcal/day intake (100 g carbohydrate, 70 g protein) in the last trimester of pregnancy for women diagnosed with GDM.14

Type 1 diabetes

● There is very limited research on the safety and efficacy of intermittent fasting in the management of type 1 diabetes. A small pilot study tested a 5:2 diet in ten people over 12 months and reported no change in hypoglycaemia and no episodes of diabetic ketoacidosis.15

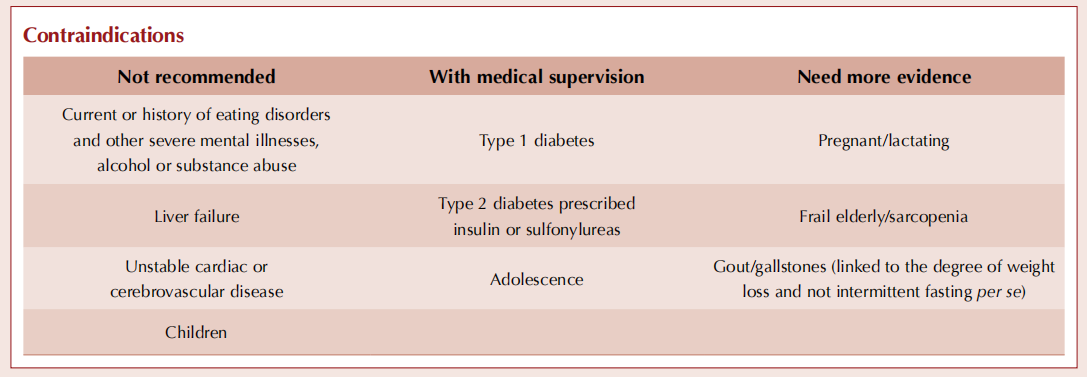

Risks and contraindications

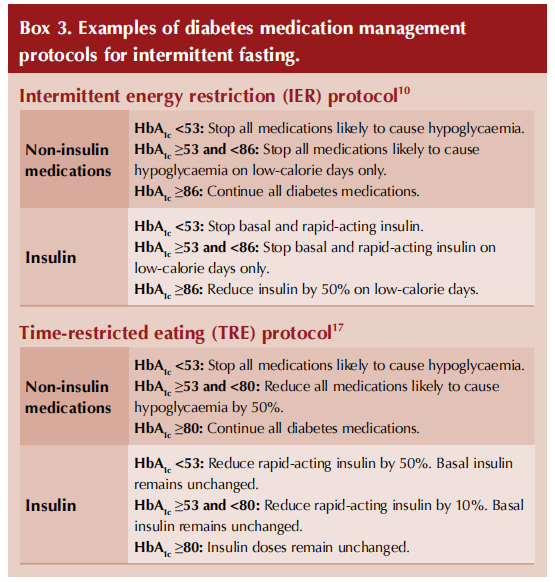

Medication management in type 2 diabetes

● There is no evidence of increased hypoglycaemia or hyperglycaemia during IER or TRE in people with type 2 diabetes and overweight/obesity on hypoglycaemic agents (i.e. sulfonylureas and insulin), as long as participants are asked to regularly monitor blood glucose and medication is adjusted per protocol10,16 – see Box 3 for example protocols.

● Antihypertensives may also need be adjusted due to the blood pressure-lowering effect of low-calorie days and subsequent weight loss.10

Lean body mass (muscle mass)

Some IER and TRE studies have reported clinically significant reductions in lean body mass in older subjects (average age 60 years), which may reflect inadequate protein intake.18 Lean body mass preservation alongside weight loss is important for health, function and maintained metabolic rate.

Mood and eating disorders

There are concerns that intermittent fasting could trigger eating disorders. However, studies of alternate-day fasting in people with overweight/obesity show reductions or no change in eating disorders,19 and no change was reported with TRE. 20 Nonetheless, healthcare professionals should remain vigilant. It is possible that people with a history of eating disorders are more likely to be attracted to this form of eating, which may enhance their preoccupation with food.

Minor side effects

● There may be some minor side effects, such as dizziness, nausea, headaches and constipation; however, these are often transient and disappear within a few weeks of starting IER and TRE. 21

● The impact on sleep is variable. Some find sleep is impaired on low-calorie days, whilst others find sleep is improved, likely due to an improvement in diet quality and not eating late at night (in the case of TRE).

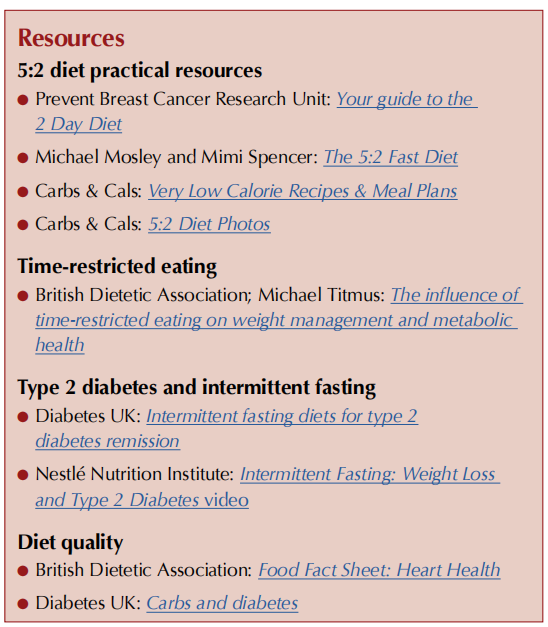

How to advise and support people with intermittent fasting

Adherence

Intermittent fasting is not for everyone and should be seen as an alternative to other dietary approaches for weight loss and improved metabolic health.

● The simple rules of these diets can make them easier to follow in the short term, but adherence with IER has been shown to decrease over time.22

● Flexibility (e.g. separating the two low-calorie days of 5:2 and moving the eating window of TRE as needed) is key to adherence. Adherence to IER and TRE is improved with ongoing healthcare professional support.

Diet quality

● What we actually eat is important for health. A healthy, balanced diet should be encouraged (e.g. a Mediterranean-style diet). Those with type 2 diabetes should moderate the amount of carbohydrate they eat and ideally choose higher-fibre and slow-releasing carbohydrates (see Resources).

● To help preserve muscle mass and metabolic rate, a good protein intake on low-calorie days and good activity levels (particularly resistance exercise) should be encouraged.

● Sufficient fibre and fluid should be encouraged, to help prevent constipation and headaches.

Monitoring

● Regular self-monitoring of blood glucose (if the person has type 2 diabetes and is on medications that may cause hypoglycaemia) and blood pressure in those who are on

● Adherence; changes in weight and, where possible, body composition (muscle mass); diet quality (e.g. Mediterranean diet score); eating behaviours (check not over/under-restricting or over-eating during non-fasting periods); physical activity levels; mood; wellbeing; and sleep.

Authors: Michelle Harvie, Research Dietitian (Prevent Breast Cancer Research Unit) Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust; Sarah McDiarmid, First Contact Practitioner Diabetes Dietitian, West Leeds Primary Care Network

Citation: Harvie M, McDiarmid S (2024) At a glance factsheet: Intermittent fasting for the management of weight and diabetes. Diabetes & Primary Care 26: 81–4

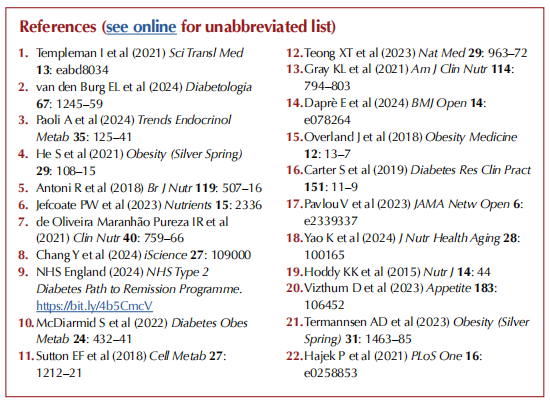

References (see online for unabbreviated list)

This article is excerpted from the Diabetes & Primary Care Vol 26 No 3 2024 by Wound World.